At the risk of sounding like a child, I will say that adulthood is sometimes hard but mostly good, and upon moments of reflection I enjoy all the wisdom and Verizon bills that I have accrued over the years. Still, there seems to be a strange cultural resistance among people my age (adults) to adulthood. Although the horrible term “adulting,” in which an adult performatively completes the rote tasks required by the stage of life that typically follows adolescence, has fortunately come to be more or less universally reviled, a new term has taken its place: “burnout.” Burnout, popularized by a viral BuzzFeed article, is when an adult becomes so overwhelmed by the tasks required by adulting, like mailing things and understanding what a deductible is, that they simply cannot go on and melt into a quivering Alex Mack pool of anxiety and dread that they then describe on social media.

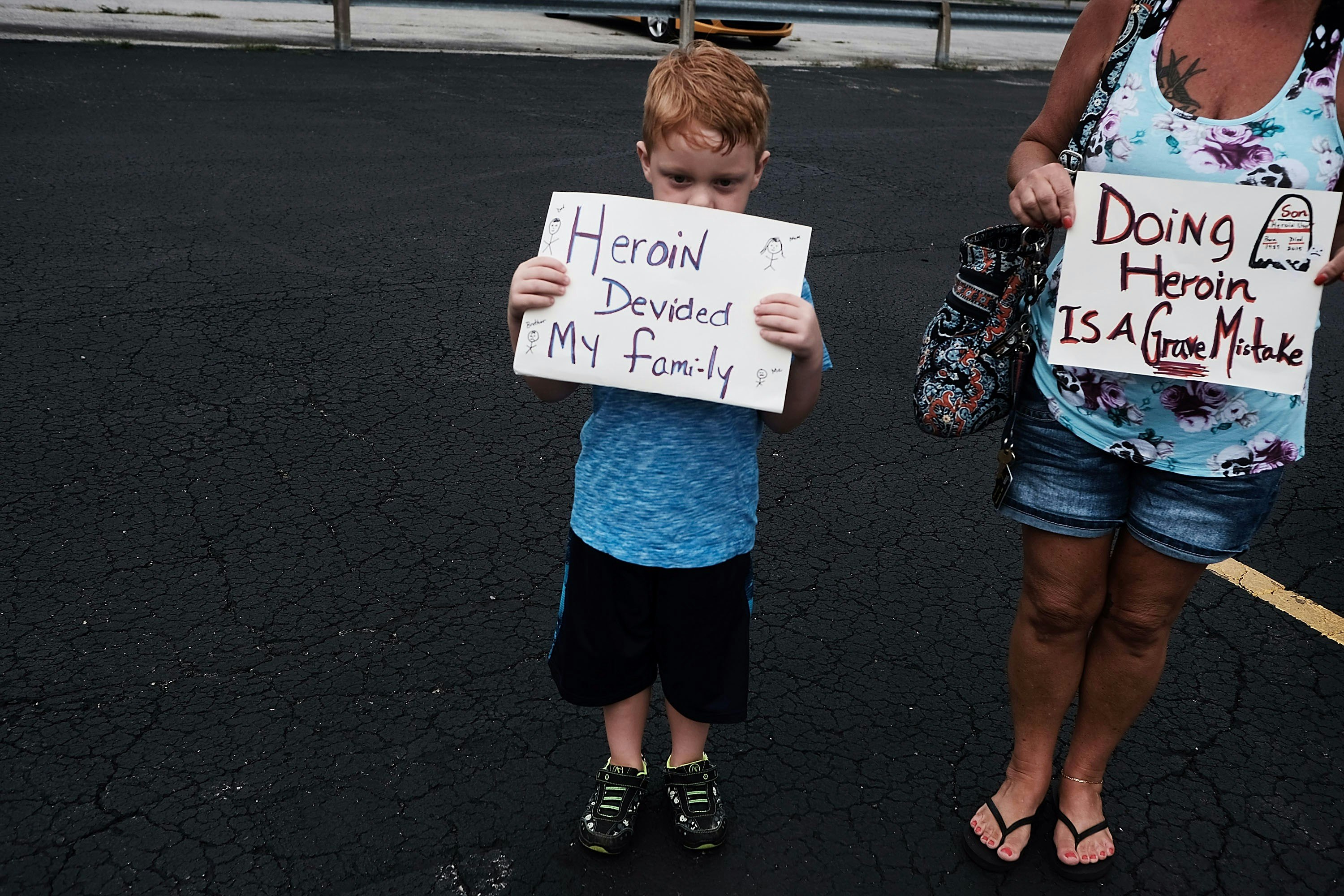

Many external factors have contributed to this phenomena of seeming emotional arrest: increased education but fewer jobs, the gig economy, Silicon Valley, global warming (?), Harry Potter, influencer culture, Donald Trump, helicopter parenting, etc. etc. People really love to blame such external factors for their problems, which is fair, but I would like to first consider some internal factors, which are very interesting and you don’t have to know what a Hufflepuff is.

The concept of adulthood can be closely related to a positive experience of solitude. In his 1958 paper “The Capacity to be Alone,” the English psychoanalyst D.W. Winnicott wrote that such an ability “is a highly sophisticated phenomenon and has many contributory factors. It is closely related to emotional maturity. The basis of the capacity to be alone is the experience of being alone in the presence of someone.” The wherewithal of healthy seclusion, Winnicott theorizes, goes back to an infant’s relationship with its mother — that a mother and child spend sufficient time together, or, more simply, are bonded by the love that forms between two people whose presence is “important to the other.”

“The basis of the capacity to be alone is a paradox; it is the experience of being alone while someone else is present,” Winnicott writes. So a mother sitting near her baby as it plays on the floor. A couple reading in the park. Your dad puttering around upstairs while you make toast in the kitchen. My friend described the sensation as “the rustle of distant activity that, because time is linear, is a promise that two people will be present together soon.” It’s the feeling that, she continued, “someone is working for the community you inhabit, and you are in your role, too.”

The concept of adulthood can be closely related to a positive experience of solitude.

I’m not sure what went wrong, but Millennials seem to have very little capacity to be alone in a healthy way. We are, by many reports, a very lonely generation. In lieu of interviewing every Millennial’s mother to find out why this is, let’s look at some data. According to a survey last year by the health care company Cigna, members of the Millennial and Z generations scored higher than Boomers and the Greatest Generation on an amazing thing called the UCLA Loneliness Scale, which rates a person’s loneliness based on a survey of 20 questions. A study by the Office of National Statistics in the UK found similar results, saying that “younger renters with little trust and sense of belonging to their area” were particularly susceptible to feelings of loneliness. An earlier survey of college students in Hong Kong reported that being online for long periods of time led to increased “feelings of loneliness over time.”

Unfortunately, I am going to have to blame social media for this loneliness. (I must also pause to acknowledge that this thesis is one favored by an all-star roster of the worst male writers including David Brooks, Andrew Sullivan, Montaigne, and Stephen Marche, in addition to Louis C.K. But I promise this article won’t be like theirs because I am not a huge asshole.) A 2018 study in the Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology found that “limiting social media use to approximately 30 minutes per day may lead to significant improvement in well-being.” A 2017 study in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine had similar findings; NPR summed them up better than I ever could:

It turns out that the people who reported spending the most time on social media — more than two hours a day — had twice the odds of perceived social isolation than those who said they spent a half hour per day or less on those sites. And people who visited social media platforms most frequently, 58 visits per week or more, had more than three times the odds of perceived social isolation than those who visited fewer than nine times per week.

Winnicott is sadly dead, so I cannot ask him if the dominance of social media in our lives might erode whatever paths to emotional maturity our earliest caregivers might have instilled in us. But there is something to be gleaned from his idea that “the basis of the capacity to be alone is the experience of being alone in the presence of someone.” Social media yammers on about connection and community when it really leads to isolation and, worse, a narcissistic immaturity desperate for the kind of human connection that cannot be borne from replying to each other on Twitter. If Winnicott’s paradox is a baby playing near its mother, social media is going to a career fair in hell: so much noise, everyone showing off, no one paying attention. The social web is engineered — gamified, in fact — to make us feel that we’re a part of a community, a conversation, a culture, but without the context that typically allows these things to flourish, such as eye contact or silence.

In her 2011 book Alone Together, Sherry Turkle, a professor of the social studies of science and technology at MIT, examines the insidious way technology and the internet fray human bonds. “Gradually, we come to see our online life as life itself,” she writes. “We come to see what robots offer as relationship. The simplification of relationship is no longer a source of complaint. It becomes what we want.” Social media is designed to make us feel that we’re in the midst of a conversation in the way that a man selling handbags in Times Square wants us to believe he’s hawking Hermes. I’m not sure if it’s because we genuinely believe in our new social schemas or because we want to believe in them, but there seems to be a lot more people carrying Hermes bags that they surely cannot afford.

Let’s examine a metaphor, put forth by the Temple University psychology professor Laurence Steinberg in a 2015 New Yorker article:

One afternoon, you’re sitting in your office with wads of cotton stuck up your nose. (For the present purposes, it’s not important to know why.) Someone in your office has just baked a batch of chocolate-chip cookies. The aroma fills the air, but, since your nose is plugged, you don’t notice and continue working. Suddenly you sneeze, and the cotton gets dislodged. Now the smell hits, and you rush over to gobble up one cookie, then another.

According to Steinberg, this is how the brain of an adolescent works, due to its enlarging pleasure centers. “Nothing — whether it’s being with your friends, having sex, licking an ice-cream cone, zipping along in a convertible on a warm summer evening, hearing your favorite music — will ever feel as good as it did when you were a teenager,” Steinberg told the magazine. The nose of an adult, he said, is permanently plugged with cotton: the cotton of maturity, restraint, and reason.

I asked Steinberg if he thought social media could be a kind of cookie, with an aroma strong enough to coax the cotton balls to out of an adult’s nose — and if that could happen, would it signify some sort of mental regression? “When we are emotionally aroused, at any age, we make bad decisions, in the real world as well as on social media,” Steinberg said. “I think most people (including adults) are less likely to self-censor when they believe they are protected by the semi-anonymity of social media.”

Unfortunately, I have to blame social media for our loneliness.

I’m going to interpret that as a “yes:” social media is at least a kind of cookie, one that overpowers the areas of our brain trying to make us form good relationships, or go to sleep, or eat fewer cookies; the evidence it has a “sex-like” effect on the brain is well-established. A 2012 Harvard studyfound that users spend 80 percent of their speech talking about themselves on social media, compared to 30 to 40 percent in real life; platforms reward self-disclosure by activating the release of dopamine in the brain. “Humans so willingly self-disclose because doing so represents an event with intrinsic value, in the same way as with primary rewards such as food and sex,” the study’s authors wrote.

A former Facebook executive even admitted to how its technology was damaging positive social interactions. “I feel tremendous guilt,” Chamath Palihapitiya said at a Stanford Business School event in 2017. “The short-term, dopamine-driven feedback loops that we have created are destroying how society works.”

By mimicking feelings of human togetherness, social media might make us feel like we are able to be alone in the presence of others (or their avatars), when really we are only being pulled further from humanity the longer we stayed engaged. In her 2015 book Reclaiming Conversation, Turkle argued that talking with someone face-to-face is a precursor to successful aloneness: “Solitude and conversation form a kind of virtuous circle. And that’s the virtuous circle our phones can disrupt,” she told the Huffington Post. “We forget how to pay quiet attention to ourselves and this disrupts our ability to be with each other. Psychology teaches us a great truth that we ignore at our peril: If we don't teach our children to be alone, they'll only know how to be lonely.”

I apologize for sounding like a dad trying to take beer away from teenagers, but it is so easy and tempting to log on and complain about our terrible lives and how the world is terrible instead of going out into the world and doing something that might even make us feel genuinely good. I might go so far as to argue that the phenomenon of burnout among Millennials is not caused by the effects of late capitalism on our lives, but by the late-capitalistic social-media platforms that purport to bring us closer to each other and the world. Such platforms have the power to trap us in a degrading circuit of commiseration, false intimacy, and narcissism, which has the capacity to simultaneously make us feel like the most important person in the world and like total shit.

I will grant you that some adults might want to be big whiny babies and no level of unplugging can change this. Fine. Cry away! But perhaps more troubling than all the complaining and basic-task impotence is the way social media has made it so that alleged adults are seemingly unable to inhabit the Winnicott paradox. I asked my friend if she could remember a time when she was last “alone together” with someone. “We never experience it,” she said. “It is at most a dual vacancy as two people look at their phones.”

As someone whose phone will likely have to be pried free from my corpse after rigor mortis has set in, I feel great guilt about this, and I’m not quite sure how to move time backward and reprogram my brain to not be so aroused by the internet. But after significantly curtailing my time on social media in the last year, I can say that it has become a lot easier, at least, to go to the post office.

Get Leah Letter in your inbox.