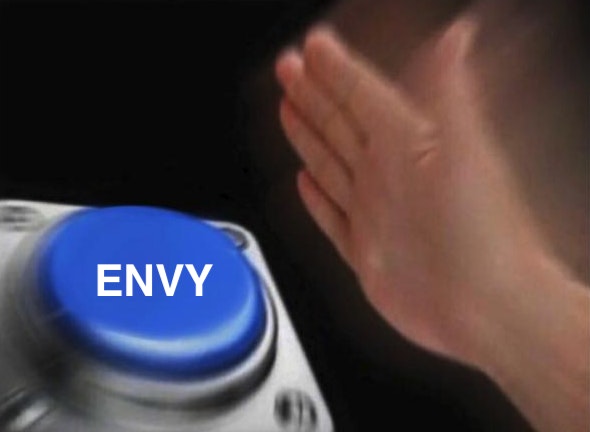

Let’s start today by talking about a tweet, which I think may be the best tweet I have ever seen. Here it is:

This tweet, a brilliant work of satire by Twitter user @bashfulcoward, adroitly mocks the state of online discourse between certain factions of media members and their fans. For the uninitiated, here’s how these conversations usually go down: A woman — in this case, JennyBuzzfeed, who represents the prototypical young, highly engaged content aggregator — tweets something goofy and perhaps willfully dumb. In a vocal conversation such a statement might be met with scorn, confusion or, worst of all, nothing, but on Twitter it is rewarded with effusive support and praise: “3.2k RTs 7.8k likes.” Beyond the serotonin-releasing likes and retweets, the nonsensical tweet is met with replies — “omg JENNY,” from “Weepy horny beard guy,” who might never talk to Jenny in real life — that serve to encourage the behavior of the tweeter.

The reason @bashfulcoward’s tweet is so perfect is that it nails firmly on the head how the insidious culture of microcelebrity works on the internet. Rewards exist for doing very little, and those who are rewarded are buoyed to the forefront of the internet’s consciousness where they… well… no one really knows what will become of them. Will they parlay social-media fame into a run for Congress? Will they live-tweet their death? Are they okay? Does this matter? In daily life, sure, because our attention and reward systems are fucked by the internet and watching that in motion grates the soul. But what about in the long term? Is this our forever discourse? Are we going to die trying to go viral, or at least watching others try, which is maybe worse? Do we want to die right now, even talking about this? Yeah, we do.

Anyway, here we go. In order to grasp the vagaries of microcelebrity culture we must first discuss what it means to be a celebrity. Leah Letter has previously examined how celebs are capitalist tools, but that is only the tip of of a very jagged iceberg in the ocean of fame. In his 2011 paper “The Unwatched Life is Not Worth Living: The Elevation of the Ordinary in Celebrity Culture,” Joshua Gamson argues that there are three types of celebrity. First there’s the traditional celebrity, an ordinary person who is “luckier, prettier, and better marketed” than your average chap, a product of the finely oiled Hollywood production machine, basically anyone included in this Venn Diagram. Then there’s the reality celebrity, who has been given a chance to compete for fame on a talent competition show or through a dramatization of everyday life (Gamson notes how many of the real Real Housewives have, once ensconced in public consciousness, used the show to market their subsequent books, restaurants, and margarita mixes to further recognition).

And then there’s the internet celebrity. Gamson characterizes the internet celebrity as one whose popularity is dependent upon their audience’s “star-making power.” “Online celebrity is driven by the energy of ‘Hey, you guys, let’s make somebody famous!” he writes. In many ways, this exchange loop democratizes celebrity, making it easier for someone who would never have access to the conventional tools of fame to become famous. The microcelebrity is a special type of internet celebrity. In her 2008 book Camgirls: Celebrity & Community in the Age of Social Networks, Terri Senft first defined microcelebrity as “a new style of online performance in which people employ webcams, video, audio, blogs, and social networking sites to ‘amp up’ their popularity among readers, viewers, and those to whom they are linked online.” These days microcelebrities can be found in untold online communities across platforms: alts right and left, fitspo, weightlifters, bikers, policy nerds, Weird Twitter and, of course, the media. They usually work for free, or at least perform hours of overtime for free, until one day some benevolent corporation sees fit to capitalize on their self-built renown.

But even though those who come to fame through microcelebrity employ unorthodox methods to do so, DIY notoriety can only go so far. As Alice Marwick, a social media researcher, notes in her 2015 paper “You May Know Me From YouTube: (Micro)-Celebrity in Social Media:” “The ability to view oneself as a celebrity, attract attention, and manage an audience, regardless of the potential downsides, may become a necessary skill” for the microcelebrity. So even though authenticity — one’s own personality, unvarnished — can carry an otherwise average social media user to some sort of fame, once one has ascended to a certain level, the authenticity that created fame must diminish if one wants to climb higher. As Marwick argues, the “messiness” that naturally comes with authenticity can be repellent or provocative to a larger audience, and thus “selectively editing oneself into a palatable product, remaining consistent, and dealing with potentially belligerent audience members are difficult tasks that prioritize performativity over any true sense of self.”

So what will happen to Jenny Buzzfeed? What does this mean for the future of our septal areas and the content we consume, and also will Leah Letter ever become a talk show in which I can appear as a disembodied head? Gamson says that the force of the internet celebrity is overstated, and he echoes Marwick in saying that those who experience celebrity online usually must transition to being a traditional celeb for any hope of permanent ascension into the Us Weekly-reading realm. Also, we must consider that the democratization of fame via social media is not outwardly good for society and may in fact be making things very bad. Gamson writes: “The ordinary turn in celebrity culture is ultimately part of a heightened consciousness of everyday life as a public performance — an increased expectation that we are being watched, a growing willingness to offer up private parts of the self to watchers known and unknown, and a hovering sense that perhaps the unwatched life is invalid or insufficient.”

It’s fine to perform life, I guess, if you want to perform it and are willing to do so mostly for free or until your soul is sucked from your body. But as my dear friend chatted me while I was writing this letter, “it's very unfortunate that the willingness to abandon shame is the key to success online.”

Get Leah Letter in your inbox.