Unlike a museum or a memorial or other places we go to try to understand horror, the internet flings users into mental trauma even as it separates them from it physically. Whatever is happening behind a screen can’t immediately hurt those reading about it on a screen, but should we choose to engage with it even passively, it produces the instinct to feel some sort of shock and horror. The problem is that the internet by nature makes it difficult to identify what the horror is, whom it is affecting, and how it is affecting them. In this gap, the act of moral performativity emerges — “THIS. IS. NOT. NORMAL! [photo of Trump grabbing Ivanka’s butt] or [photo of Jeff Sessions drinking a milkshake through a swirly straw] or [photo of a monkey reading the Constitution]. (You can fill in the blank with whatever your “not normal” is.)

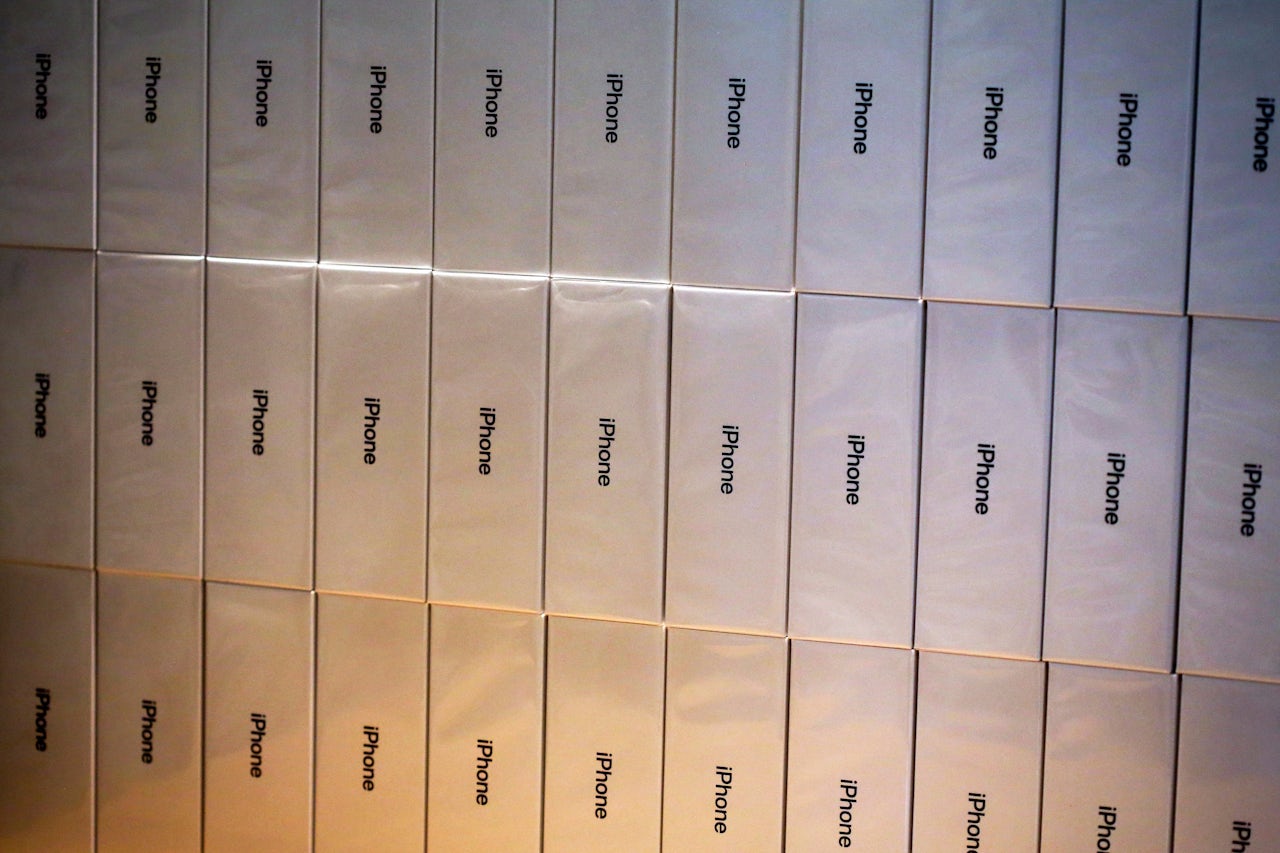

One thing I complain to my therapist about a lot — and I’m very sorry to my very kind and wise therapist for existing as his patient, but as he would say, it’s not my fault I was born! — is feeling alienated in social settings because everyone is always on their phone. This is not really fair to the “everyone” I am mentioning here, because I am also guilty. My left hand might as well be a phone, it would make things easier. I wish I could not be on my phone as much, but in social settings when people pull out their phones to broadcast the sunset or see what new ridiculous horror has rained down in Washington, I pull out my phone too. The phone has become our new defense mechanism in the face of too much reality: we go to it both to remove us from seeming trauma and to bring us closer to it — but only the former can actually happen. If there is aggression implicit in every use of a camera, as Sontag wrote, there is passivity implicit in every use of a smartphone to express solidarity with someone else’s struggle. Being online can traumatize a person on an individual level, but that experience shouldn’t be mistaken for the embodiment of someone else’s pain.

The phone has become our new defense mechanism in the face of too much reality.

In her book Performing Feeling and the Cultures of Memory, Bryoni Trezise, a professor at the University of New South Wales in Australia, discusses moral performativity in the context of visiting concentration camps. Trezise uses Dachau as an example, writing that the camp “stages the history of victim identities as an affective residue located at the site, one that pre-exists the spectator bodies who experientially source it.” In other words, concentration-camp memorials acknowledge that the visitor wants to feel what a concentration-camp prisoner felt in order to bring them closer to that trauma; the goal is to allow visitors to “imaginatively explore… history in lived memorial space.”

Trezise writes of Dachau: “While visitors can only ever corporeally misrecognize the site’s historical repertoire, it nonetheless aims to produce a forceful alignment between feeling like a Jew and feeling for Jewish victims.”

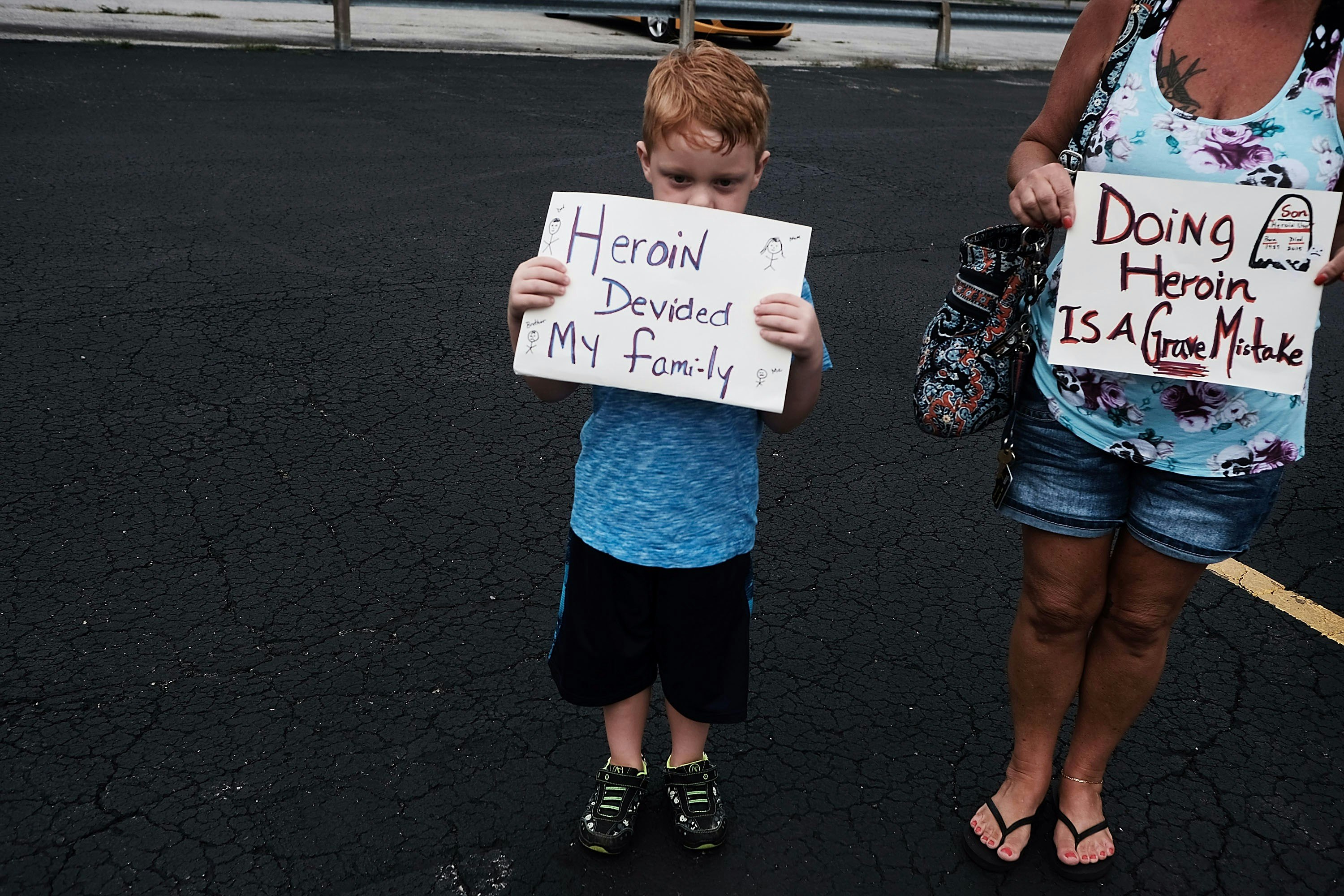

But this operation is plagued by a problem, Trezise says: “This very promise of identification involves… a sensing of Jewish victims as it is produced in relation to a sensing of visitor selves.” So, in order to truly feel trauma, well, you had to have been there. Visiting a site of trauma after the trauma and wanting to be moved by it lends itself to a phenomenon University of Cincinnati professor Gary Weissman calls “the fantasy of witnessing.�� Weissman writes that Americans are “haunted not by the traumatic impact of the Holocaust, but by its absence,” and when we study the Holocaust “we are not overcoming a fearful aversion to its horror, but endeavoring to actually feel the horror of what otherwise eludes us." It’s kind of like theories about women and true crime: we seek to process the horror to which we risk being subjected — but this does not ultimately help us understand that horror any better.

In order to truly feel trauma, well, you had to have been there.

Who actually wants to experience trauma? As Weissman writes, “one’s own place in the hierarchy of suffering has much to do with one’s professed ability to ‘feel the horror.’ A person’s intellect and moral fiber are measured by the degree they have come to ‘endure the psychic imprint of the trauma.’”Also known as: moral performativity. Non-witnesses want an authentic relationship with trauma; witnesses wish they never had one. As Weissman writes, this is “the kind of wish only one who was not there could have, and only then because one knows it cannot be fulfilled.”

“Direct experience” is a funny thing today. The internet makes it easy to see traumatic things occur in real time; everyone who is watching along thinks they have an authentic relationship to those things. The resulting knee-jerk reactions take on a patina of credibility which, I suppose, is why everything is so awful all the time. The question of our social-media age is whether such performativity can effect real change. Because broadcasting is ultimately a self-centered pursuit, I’m thinking no, but I’m hoping to be disproved.

Get Leah Letter in your inbox.