The media covers drugs in a very weird and retrograde way. I've noticed a few extremes. Stories are either unusually judgmental of drugs and drug users (“Local Teens are Sinning by Doing Weed”), super naive (“The Story of How a Rich, Highly Educated White Father and Upstanding American Citizen Became Addicted to Drugs, Despite the Fact That He was Rich, Highly Educated, and White”), or inordinately aggressive (“I Did Heroin in My Eyes With ISIS”) (that example is obviously Vice).

There was a big story in the New York Times this past weekend about a lawyer who became addicted to heroin and eventually died from a bacterial infection related to intravenous drug use. You can go read it if you want, before I tell you why I thought it was lacking. [Pause] Okay? Okay. The story is by Eilene Zimmerman, the ex-wife of the lawyer, who is only identified as Peter. It is a painful and raw account of a man’s death, but it also reveals a lot about how poorly drug addiction is portrayed in the media.

The article is framed as a sort of journalistic inquiry into how no one around Peter knew he was a heroin addict, despite the fact that he was getting syringes delivered to his house in bulk and displayed the classic, haunting symptoms of a wretched addiction. But what it really hammers at is that Peter was very smart and successful and therefore his addiction, only discovered upon his death, came as a shock. Some excerpts:

“Not only was Peter one of the smartest people in my life, he had also been a chemist before becoming a lawyer and most likely understood how the drugs he was taking would affect his neurochemistry.”

“That day in Peter’s house, the emergency medical workers told me right away that it was probably a drug overdose. I remember saying, ‘That’s impossible.’ After all, I said, he was a partner at a law firm. He had an Ivy League education.”

“In many ways, Peter’s personality and abilities read like a wish list of qualities for a lawyer. Trained as a scientist, he approached problems in a deliberative, logical way. He was intelligent, ambitious and most of all hard-working, perhaps because his decision to go to law school was such an enormous commitment — financially, logistically and emotionally — that he could justify it only by being the very best.”

You can see the implication here: that being smart, successful, educated and, yes, white, are traits incongruous with drug use and addiction. Zimmerman fully acknowledges that she was clueless when it came to drugs and addiction, but her dubiousness underscores the inadequate way stories of addicts are told in the media. Wealthy, elite (and yes, predominately white) ones like Peter are given the cover of the Times Sunday Business section; non-white ones, well, their stories might never get told — and if they do, they get told as crimes (Zimmerman’s article makes no mention of race).

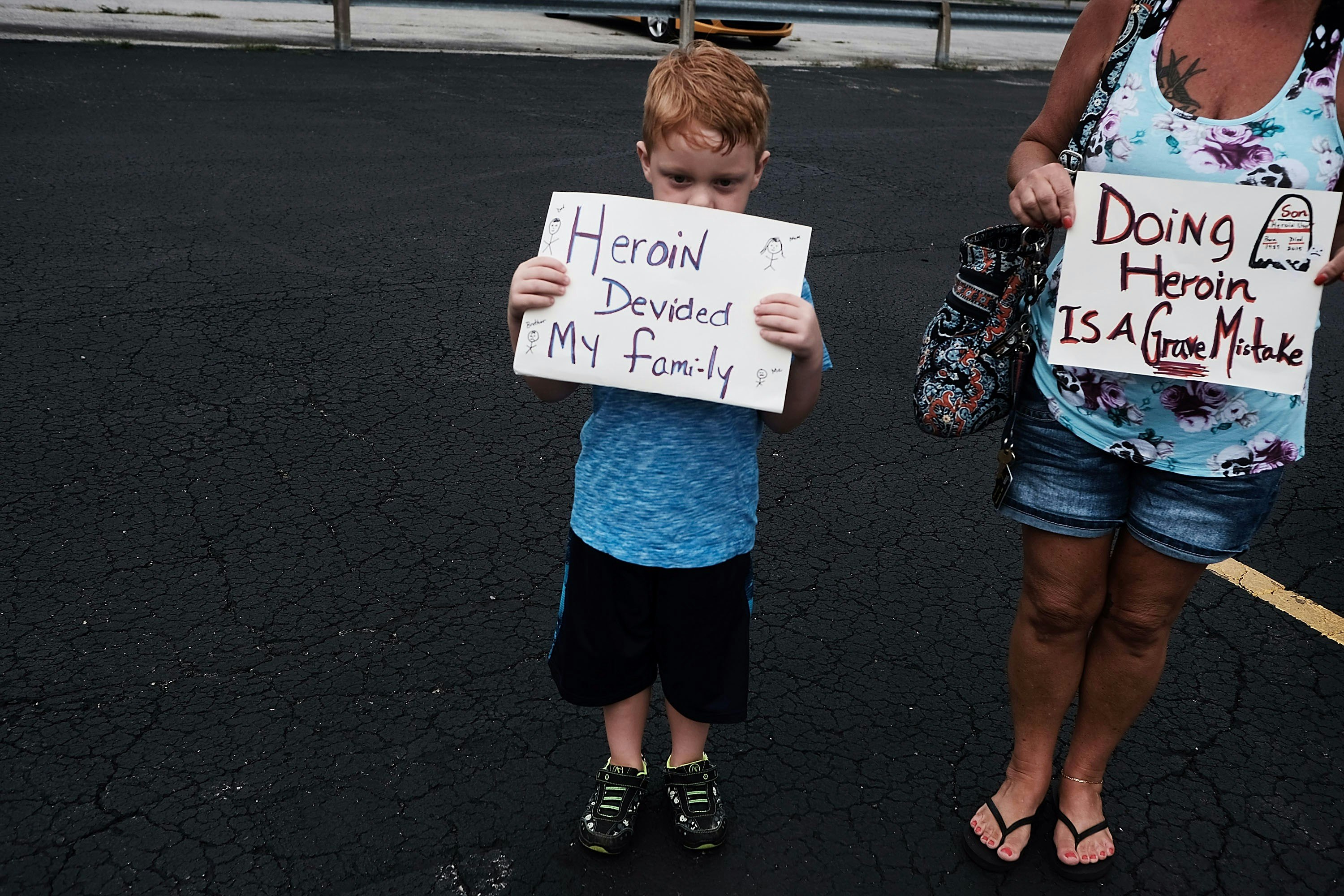

An October 2015 article in the Times titled “In Heroin Crisis, White Families Seek Gentler War on Drugs” highlights this disparity: “When the nation’s long-running war against drugs was defined by the crack epidemic and based in poor, predominantly black urban areas, the public response was defined by zero tolerance and stiff prison sentences. But today’s heroin crisis is different. While heroin use has climbed among all demographic groups, it has skyrocketed among whites; nearly 90 percent of those who tried heroin for the first time in the last decade were white.”

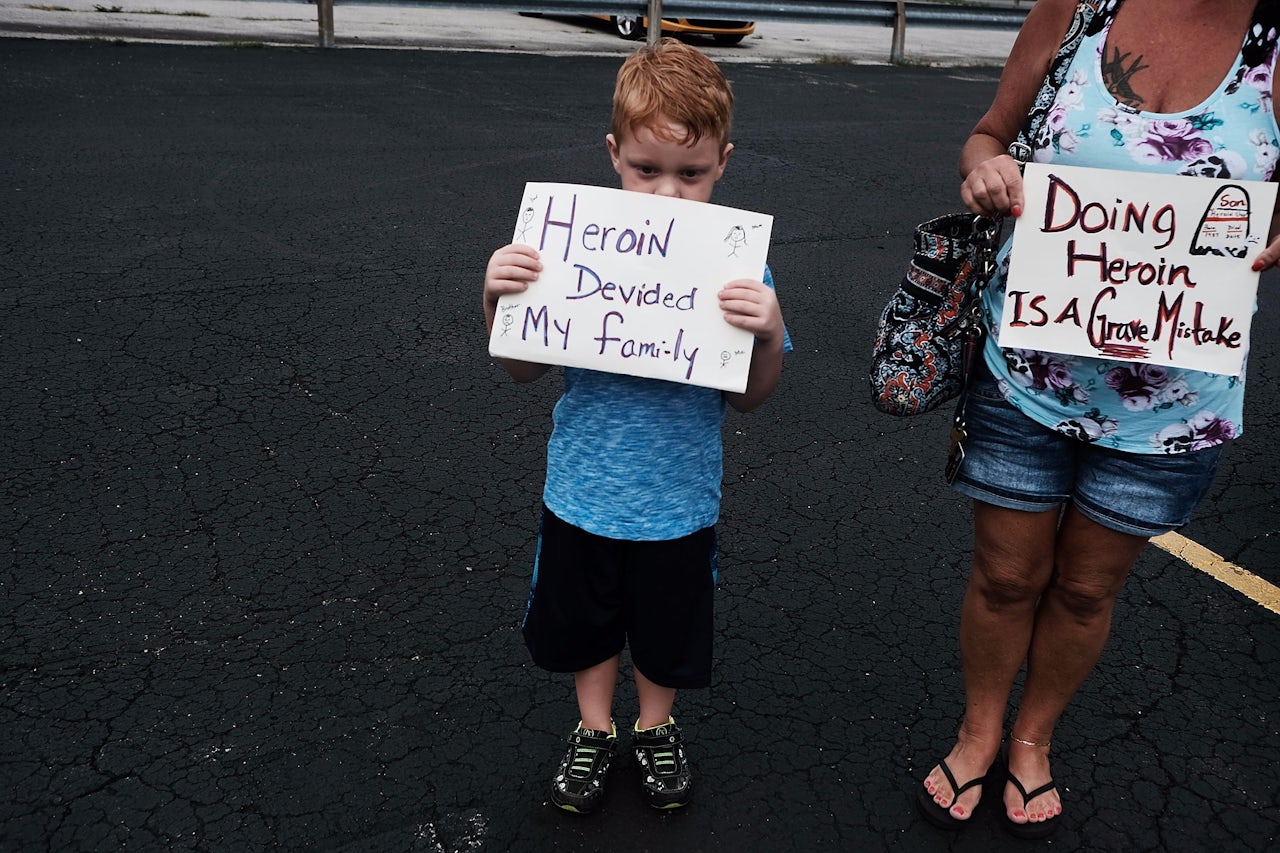

We can see this shift mirrored in media coverage of the separate epidemics. As Lauren Krisal wrote for Reason earlier this year: “The drug addicts du jour are no longer so ‘other’ — neither the poor, urban blacks that fueled crack cocaine panic nor the poor, rural whites of methamphetamine lore. They're ‘our sons, daughters, brothers, and sisters,’ they’re community members.” To the media, black drug addicts are criminals, white ones are humans. Medium blogger Son of Baldwin astutely captured this sentiment in a headline on one of his posts: “The Media Treats White Drugs Users Like Angels Who Lost Their Wings and Treats Black Drug Users Like Demons Who Must Be Returned to Hell.” And the real-world consequences of this are manifold — when drug addiction becomes a white-people problem, policymakers respond in kind.

This is not to say the media does not bear self-inflicted wounds when it comes to drug coverage; the canonical example of journalistic fabulism is still “Jimmy’s World,” a fake story of a child drug addict that the Washington Post published in 1980. The story won a Pulitzer before being retracted. In a piece for Time on the ill-fated article’s 30th anniversary, neuroscience journalist Maia Szalavitz analyzed its lasting impact. “Rarely mentioned in media discussions about fact-checking and editorial credulity, however, is the key reason that no one seemed to question ‘Jimmy’s World’: the fact that the story was about drugs and addicts,” she wrote. “The topic of illicit drug use has an ‘anti-skeptic’ effect on the media. If the explanation for any statistic or phenomenon involves drugs, then you’re pretty much guaranteed that no editor will query it.”

There was another recent article on drugs that rankled me in its cluelessness. This one was by the Associated Press, and titled “‘It’s Raining Needles’: Drug Crisis Creates Pollution Threat.” The article details how discarded syringes could be a public health threat, and although there are no reports of non-addicts becoming ill from a discarded syringe, one child put one in her mouth.

Upsetting stuff, certainly. But what’s really curious is that the article makes no mention of the humans on the other end of the needle — the anonymous addicts, whose lives are in danger every time they inject themselves, more so than a kid who picks up a stray needle. The mayor of Haverhill, Mass., James Fiorentini, provided a particularly illustrative quote: “We are all trying to get a grip on the problem,” he said of the discarded needles in his town. “The stuff comes from somewhere. If we can work together to stop it at the source, I am all for it.” That “somewhere” is the diverse world of addiction, a place that is humanized in some very messed up ways, or not at all.