Last week I went to Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland is not an edgy or particularly fashionable place to visit. In many regions sheep outnumber people. The Titanic was built there and we all know how that ended. The radio plays a lot of Ed Sheeran. But there is a lot to be learned there about people who hate each other.

My traveling companion and I arrived in Belfast a few days after Martin McGuinness, the former deputy first minister and Irish Republican Army leader, died. McGuinness was a controversial figure, like most politicians who gained prominence during the Troubles, the three-decade period of strife between the Unionist Protestants and Republican Catholics that terrorized the country. On the one hand, he likely ordered many deaths through his involvement in the IRA: “Behind the smile, Martin McGuinness was a mass murderer with menace in his eyes — who only turned to peace when he was beaten,” proclaimed the Daily Mail. On the other, he was a talented politician instrumental in bringing a peace to the country, and eventually formed a media-friendly relationship with his former adversary, the evangelical loyalist Ian Paisley (the pair were dubbed “the Chuckle Brothers”).

Belfast had more or less emptied out for McGuinness’s funeral. An Irish politician’s worth is measured not by how many people attend their victory parade but by how many show up to their funeral, and McGuinness’s, as the Guardian reported, was the closest thing his embattled hometown of Derry had “experienced to a state occasion.” McGuinness was buried there in the Republican section of a cemetery; Bill Clinton eulogized him. A laminated computer print-out posted to the gates of city hall in Belfast told visitors that a book of condolence in McGuinness’s memory had been opened. The sign was covered in some sort of dough as if a scone had been thrown at it. Our tour guide, a jocular Catholic named Kevin, told us that most of the fleet of cab drivers who take visitors on so-called “Troubles tours” of Belfast had gone to Derry to mourn.

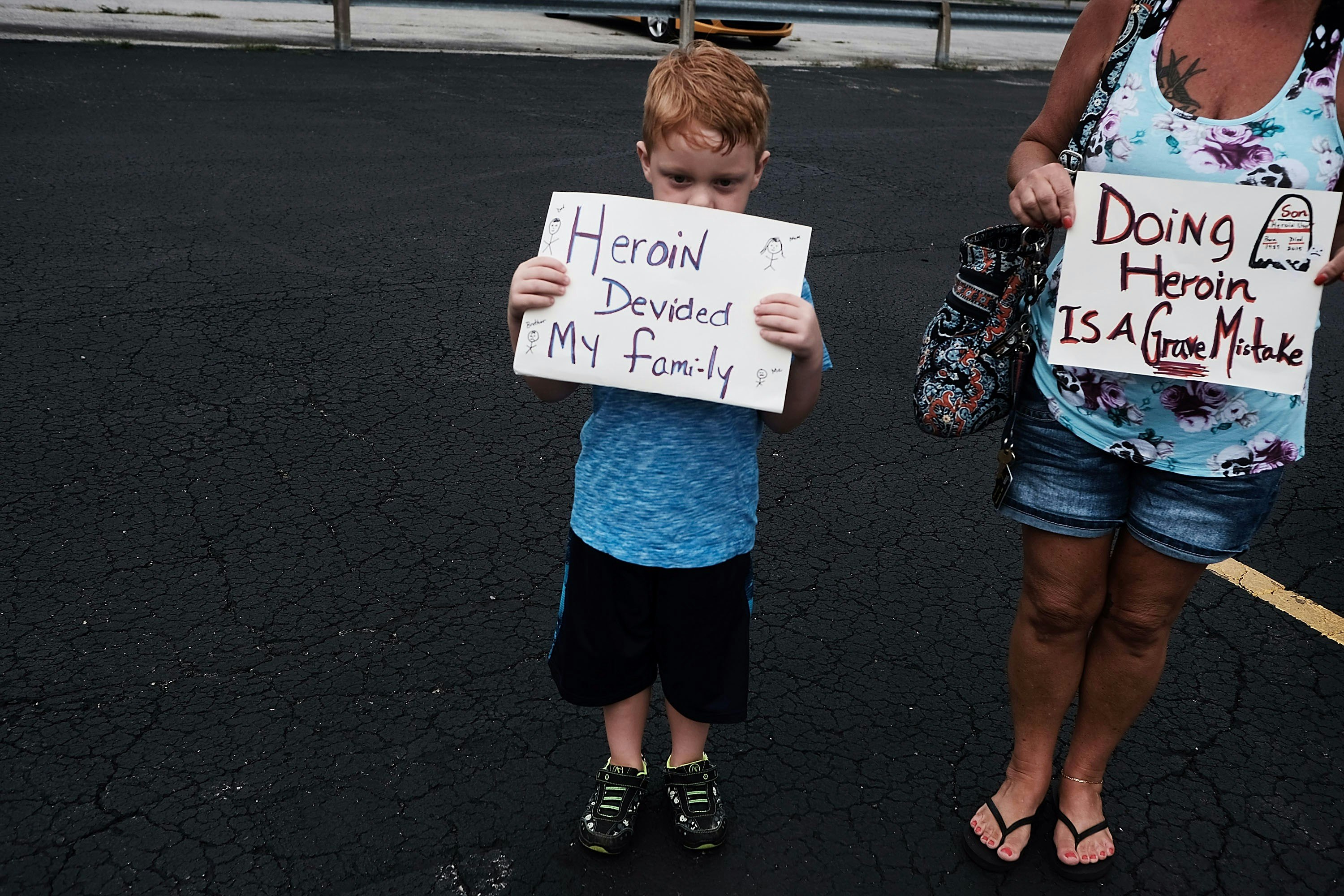

Kevin drove us around that day to show us the walls. Belfast is still divided by them: Catholics on one side, Protestants on the other. At 6:30 each evening, gates close off one side of the city from the other. Despite the formal peace process that commenced in 1998, the country remains largely, and actively, segregated. Ninety percent of children in the country go to schools according to their religion. In Belfast, 94 percent of public housing is segregated. Despite positive discrimination policies, less than a third of the Northern Ireland police force is Catholic.

Murals reflecting this state of affairs span either side of the walls. The Catholic murals pay homage to the Republican struggle for independence and honor men like Frederick Douglass and Nelson Mandela. (The absence of women in the murals is notable even though there were many female radicals; one mural does feature an IRA secretary.) The Protestant murals are more menacing — one, situated on a hillside looking down at the city, features gun-wielding soldiers and the slogan “Prepared for peace, ready for war.” Another confusingly depicts a dead Unionist wearing a beret that bore a Star of David. Kevin explained that although many of the more modern Unionists were akin to neo-Nazis, they aligned themselves with Israel because the Catholics expressed solidarity with Palestine.

The Troubles germinated in discriminatory housing practices carried out by Protestant Unionists, who retained control of the northern part of Ireland after the country was split in two in 1920. In his book on the Troubles, Tim Pat Coogan tells the story of John Currie, a Catholic lorry driver who was in need of a new home because, well, he was Catholic and on his way to having many children. In order to obtain a larger house, Currie had to present his case to the chairman of his local district council, a powerful Protestant named Moses Busby. Coogan described Currie’s meeting with Busby:

“As befitted a man on an important occasion, Currie had worn his Sunday suit for the interview with Busby, who indeed turned out to be decent enough. They got on together as Christians should. Then, having explained his mission, Currie, as the liturgy demanded, discreetly produced a five-pound note, ‘to make up for any trouble’ that his request might cause. Busby graciously accepted the large white English banknote, folded it carefully, put it away, and, assuring his Catholic caller that he was ‘a dacent man,’ delivered his verdict on Currie’s request: ‘The next time one of your own leaves a house vacant I’ll see that you get the first offer.’”

Catholics were further oppressed by the franchise up until the Troubles, which was tied to property ownership and manipulated in Unionist favor by excessive gerrymandering. Homeowners got one vote, those who owned more than one home could vote more than once, and those who lived in public housing or were renters were not allowed to vote. Thus Catholics, who were mostly unable to own property because of Protestant control, were denied a voice in the majority-British government, and their living conditions deteriorated. Anger fomented.

It was a raw day and my friend and I asked if we could stop at a nearby shop for tea. Kevin said sure but awkwardly hung back when we went inside; the shop was in a Protestant neighborhood and he didn’t want to be seen entering an establishment in what was still considered enemy territory. We grew very fond of Kevin even though we could only understand about every fifth word he said (a Dubliner later told us that people in Belfast talk “as if they had marbles in their mouths”). Some of Kevin’s claims seemed dubious, like when he told us that Belfast had the best hospital for heart transplants in the world, or that King William was a good fighter, “even though he was bisexual.”

I didn’t expect to be overwhelmed by the tour, but I was, especially after we stopped at the site where the Divis Flats once existed. This was where Jean McConville, a widowed, Catholic mother of ten who was erroneously suspected of being a British spy, was snatched from her home in 1972, becoming one of the nine people “disappeared” by the IRA during the Troubles. A New Yorker article from 2015 told of McConville’s now-adult son catching a taxi in Belfast, only to realize that the driver was someone involved in his mother’s death. Belfast is that kind of city — its history of violence, so recent and distilled, can make it feel suffocating. It’s one of the most disquieting places I have ever been.

We left Belfast for the republic and drove to the coast. We met a chatty man who, like most people we met on the trip, was eager to boast of the Irish’s accomplishments in America. Did we know that the man who designed the White House was Irish? Yes, from Kilkenny. Joe Biden — Irish. County Louth. Donald Trump was actually the first president not to have Irish in him (have not confirmed any of this). I bought a memoir by a former IRA man, Eamon Collins, who described in emotionless detail the satisfaction he gleaned from helping to carry out killings as a young recruit and his later regret for his actions. After the book was published, he was murdered near his rural home, beaten and stabbed to death while walking his dogs on an early winter morning. Gerry Adams, the president of Irish Republican party Sinn Fein, said that Collins had "many enemies in many, many, many places” (Adams, who was very close to McGuinness, has denied involvement in the IRA despite evidence to the contrary).

I realized then what had overwhelmed me at Divis Flats. In a world where hate is everywhere, Belfast felt unique. Unlike the American south, or Germany, Northern Ireland was resigned to its divisions. Beyond the specter of sectarian hatred, there were layers of abhorrence: The hate that festered in the ligaments that connected people on the same side of a conflict. The noxious mixture of pride and hate that was justified as a path to peace. These forms of hate could not be controlled by walls; they easily permeated them. We had planned to go back to Belfast, see the Titanic museum and all that, but I no longer felt up to it. We went to Scotland instead.

Get Leah Letter in your inbox.