IT HAPPENED

is a series reflecting on our memories of 2017, one month at a time, as we head into the new year.

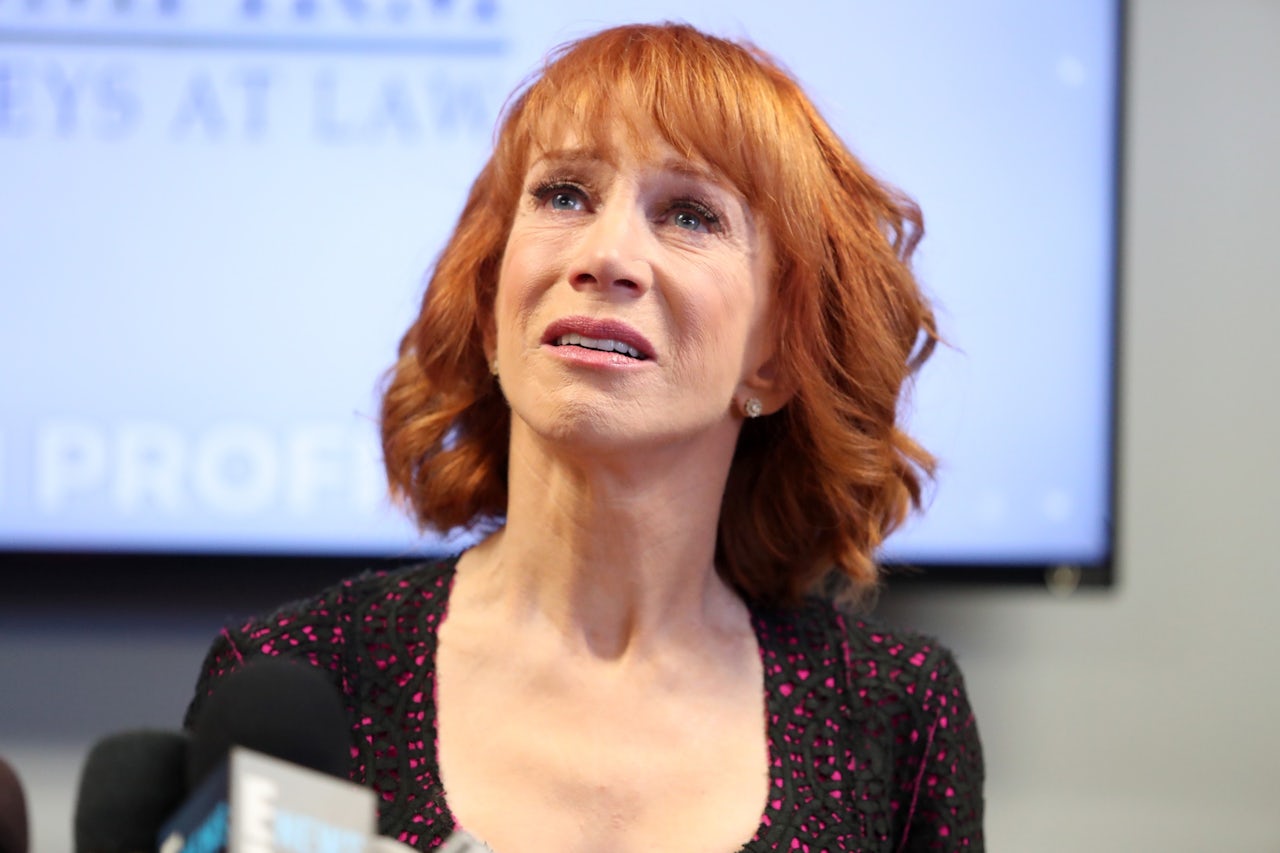

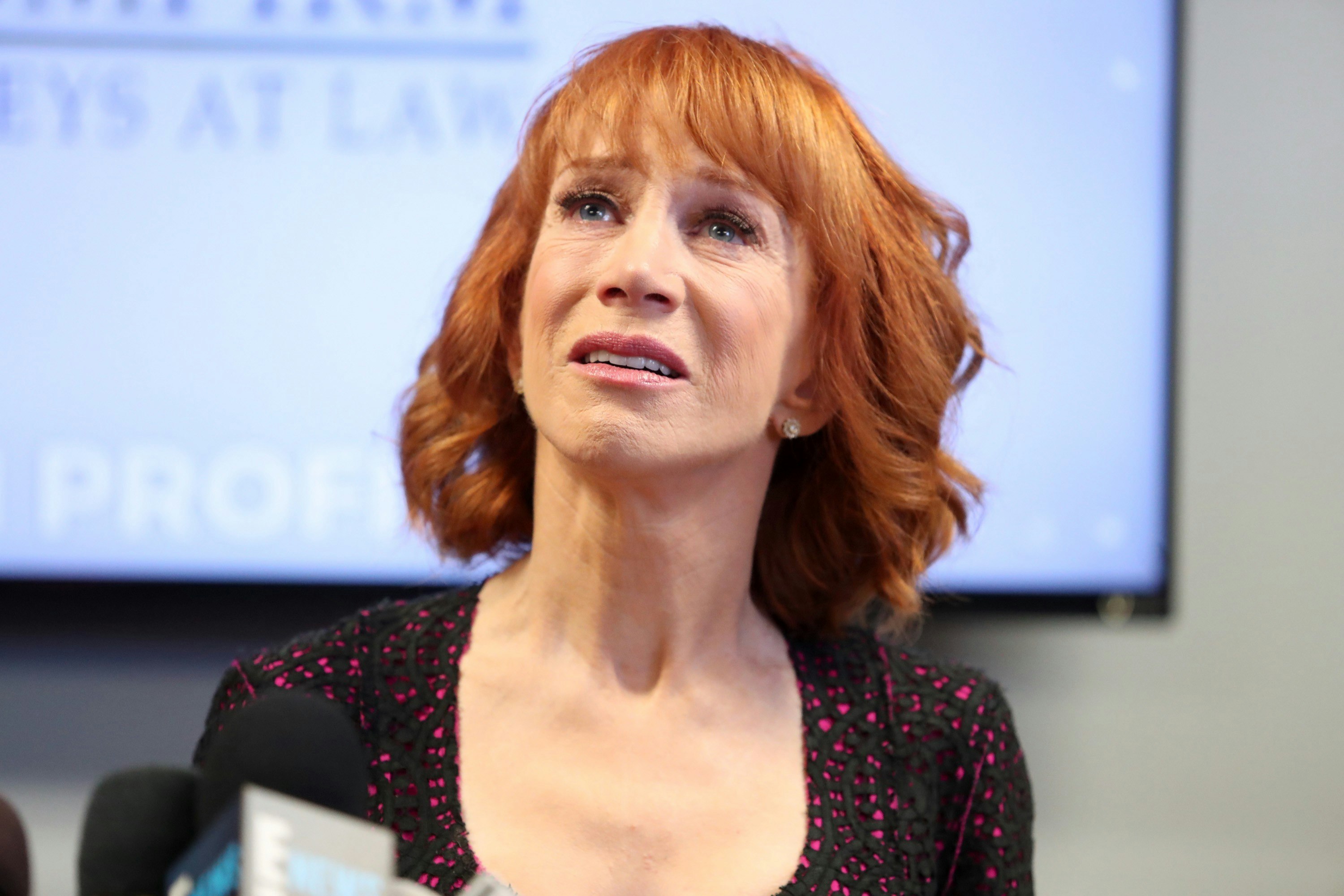

There was something desperate and sad in the photos of Kathy Griffin holding what was supposed to be the severed head of the President of the United States. Here was a late-period ‘90s comedian perhaps most famous for a reality show about how unfamous she was, face slack and mouth pursed as she gripped her political metaphor. Kathy Griffin, really? Nobody in the world was begging for her to emerge as a leading political voice, and yet here she was, intent on making a point about … well, I was never really quite sure.

That Griffin was met with universal outrage, from the conservatives who insisted she intended to literally murder Donald Trump, to the liberals who chided her lack of tact, was an entirely predictable outcome. Subtext is not always easy to divine from a still photo, and regardless of intent it really was an artlessly unpleasant image. But it was astonishing to see how high up the controversy went: Within hours, Griffin had been denounced by the president himself, who turned the full force of the gin-blossomed radio corps and Pepe-brandishing failsons onto the former co-star of Suddenly Susan. In the last few years, I’d seen countless people excoriated for making a vulgar yet hardly serious joke about the wrong subject. This was something more intense: Hard evidence that it was possible for poor taste to become, however briefly, the most dominant topic in the country, a thought chilling enough to stay the hand of thousands of would-be jokesters.

The writer Kyle Wagner once proclaimed that the future of the culture wars was Gamergate — a world where every action and comment would be cleaved of its context, and warped to prove some flawed thesis concocted by the most humorless, partisan dolts. In this world, you could be a sarcastic little shit, as many of us often are on the internet, and end up costing your employers millions of dollars. I, and most of the people I know, would be completely toast, because increasingly bleak humor often feels like the only sane response to the horror show — especially now, when almost all public discourse bends back toward Trump, whose existence is a satire unto itself. Without the freedom to roll our eyes at these chucklefucks, the daily parade of hypocrites and bigots would leave one as mentally unhinged as any Korn video.

When everything is so fucking stupid, the most refreshing point of view comes from those who can simply say so. Just as the buffoonery of the Bush era gave rise to smirking liberal comedians like Jon Stewart, Trump allowed leftists like the members of Chapo Trap House, whose mixture of aggrieved wonkery and arch toilet humor is pretty much the dominant online praxis for every Bernie Sanders supporter under the age of 30, to flourish. Still, it was startling to see how many professional comedians seemed to think it their task to take down Trump, though perhaps less surprising to witness their attempts at leveraging it into success. Was there anything more galling than watching the proficiently bellicose Alec Baldwin turn his wine-drunk impersonation of the Donald into a book deal? Was there anything more futile than any Saturday Night Live skit or late night talk show routine about whatever it was Trump did that week? It trickled down from television to Twitter; suddenly, everyone with a verified account and a passable joke was an expert.

I’ve never been a fan of comedians — comedy, sure, because I’m not a ghoul. But I grew increasingly wary of how many comedians had an inflated opinion of their ability to comment on the world, just because the nature of their work was to braid observation with judgment. They’re supposed to understand the way it is, since they make a living by riffing on the absurdities inherent to modern life, and so commentary about some piece-of-shit partner or piece-of-shit guy on the bus soon shaded into multi-tweet threads about how Trump was threatening a Constitutional crisis.

They were all part of the #resistance, whatever that was. The spectrum seemed to flow from community organizer to aggrieved poster — a person who spends his every moment in the service of some collective, tangible action against the president and his psychic agenda, and a person who spirals into inanity about how Russia flipped Trump because of kompromat, or something. Never before had it been so easy to identify as a freedom fighter. All it took was a hashtag, and the indefatigable self-righteousness that one is doing all they can.

Before her controversy, Griffin was not immune to the allure of this pomposity. Between the beginning of Trump’s presidency on January 20, and May 18, she tweeted #resist 44 times. After that, the word was absent from her lexicon. Griffin was initially apologetic. “I’m a comic,” she said in a video. “I crossed the line. I move the line. Then I cross it. I went way too far. The image is too disturbing. I understand how it offends people. It wasn't funny." But only a few months later, after correctly sensing how stupid it had all become, she retracted her apology entirely. “The whole outrage was B.S.," she said. “The whole thing got so blown out of proportion.” Her career did not implode, as she’d predicted, and she made her return to the stage in Los Angeles while wearing a Trump mask and brandishing the middle finger.

It was too simple to call this brave, because after all Griffin is at least moderately rich, but it was at least honest to see her drop the charade. Yes, she knew the image was disturbing; yes, she meant to offend people; no, she did not see the point in being contrite toward a bigoted pervert who rose to political prominence by befriending the maniacs who wanted to see Barack Obama hung for treason. She understood, as many people need to, there was no point in playing fair, and for a moment glimpsed the true cost of engagement for someone as privileged as her, and many of us, who experience the worst parts of Trump’s administration through a screen.

There is a fantasy, found most commonly in op-ed sections, that civility combined with the truth will be enough to beat back the spewing hordes — that fingers wagged at just the right tempo will summon some kind of shame or humility in the people who gleefully parrot Mike Cernovich. I can’t see any bravery in this appeal to decency — only a diffuse cowardice in the refusal to recognize the conditions of the game for what they are. And when you’re up against people who would be happy to see you dead, or at least not accounted for, insisting on an imagined compromise contrary to what the people really want makes you Charlie Brown, forever kicking at the mirage of bipartisanship.

Hence the appeal of rudeness, and calling these ridiculously uncool jokers out for what they really are. There were moments this year when I worried about the use of humor as a rhetorical strategy. The downside of jokes is that you’re never being quite as clever as you think, especially not when the other side threatens to Gamergate you right to hell. I have met too many people who can’t pick up on notes of sarcasm or irony to know that it can never, ever become the primary means of communication meant to reach millions of the people; most people in this country aren’t that hollowed out, thank God.

Even so, we may be slowly forging a collective understanding of what is just a joke, however unsexy the process. I gasped when MSNBC fired a part-time contributor because of a clearly in-bounds gag he’d made on Twitter almost a decade ago, and was heartened — shocked, really — that they hired him back immediately. My friend feared that “bad faith” would become a phrase as meaningless and weaponized as “fake news” by those who really were acting in bad faith, but it seemed that all we had to do was to not fall into the trap — to not hold ourselves up to imagined standards of conduct that the haters and losers never, ever will. We could speak to each other honestly; we could tell simply unfunny jokes without fear of causing a world war; we could call a failson a failson. We could be the first people to learn something from Kathy Griffin, and the chopped head dangling from her grasp.