Last week, a man’s open Instagram “love letter” to his wife (or, really, to his wife’s “curvy body”) went viral, as open letters are often intended to do. Robbie Tripp, the man behind the letter, was quickly praised for his public, #relationshipgoals-worthy display of love — and then rightly criticized for thinking his love for his “curvy wife” was extraordinary or brave. Tripp’s post was more than a cheesy, if mediocre, public declaration of love: It was shameless self-promotion for his own public speaking career and for his wife’s “body positive” fashion blog. Tripp may not have known the post would go viral, but his wife, Sarah, pitched it to at least one publication after it started picking up steam, apparently in hopes to use their newfound microcelebrity to cash in on the increasingly lucrative body-positivity movement.

The Tripps, like so many before them, are cravenly using body positivity to sell you shit. Despite the criticism, it’s working.

It’s not rare for brands — and for people who want to be A Brand — to use body-positivity to market themselves, with varying degrees of success. Earlier this year, Dove announced it would be selling body wash in limited-edition bottles that represented women’s myriad body types. Like the Tripps, Dove was mercilessly mocked. But other brands that use body-positivity, “empowerment,” and feminism as a marketing strategy are often celebrated for bucking conventional beauty norms. Blink Fitness, a barebones gym chain with locations in New York, New Jersey, and Philadelphia, was praised for a January ad featuring “real members” from its gyms across the country instead of models. Last year, Nike was similarly praised for a sports bra ad campaign that featured models with different body types. Aerie, a bathing suit and lingerie brand owned by American Eagle Outfitters, has been putting out unretouched ads featuring “real women” since 2014. Last month, Proenza Schouler commissioned a video purportedly for Planned Parenthood that featured a cadre of #influencers, including Grimes, Jemima Kirke, and models Hanne Gaby Odiele and Hari Nef, none of whom ever uttered the words “Planned Parenthood.” Instead, they discussed gender, notions of femininity, and their relationships with their own bodies.

The response to body-positive advertising has been mixed but skews favorably, especially from ostensibly feminist websites that seem to have little purpose other than convincing young women to buy things. (The word “empowering,” for example, appears more than 7,000 times on Refinery29 and nearly 3,500 times on Bustle.) These websites regularly run uncritical, press release-like posts praising brands and products — like a makeup line with “self-affirming” packaging and Khloé Kardashian’s clothing line — for being “empowering” and therefore feminist. These brands only get criticized when, like Dove, their advertising ever-so-slightly crosses the line, or when their clothing doesn’t fit as advertised.

The messaging has changed, but the purpose remains the same: Companies want you to buy their shit.

There’s money to be made in marketing products as inherently “empowering” instead of as tools women can use to fix problems society tells them they have. Makeup is no longer a way of covering up blemishes, but instead a tool of self-expression. Gym memberships and activewear aren’t for losing weight, but for gaining strength. Bath bombs, spa treatments, and manicures aren’t occasional indulgences; they’re an empowering form of self-care. The messaging has changed, but the purpose remains the same: Companies want you to buy their shit, and they’re happy to trick you into thinking consumerism is a form of self-expression to do so.

In her book We Were Feminists Once, feminist writer and Bitch magazine cofounder Andi Zeisler calls this phenomenon “empowertising:”

The idea that purchasing itself was a feminist act became a key tenet of emerging marketplace feminism, an embrace of feminism that’s depoliticized, decontextualized, and less about ensuring equal rights for women than about empowering them as consumers,” Zeisler writes. “Empowertising builds on the idea that any choice is a feminist choice if a self-labeled feminist deems it so, but takes it a little bit further to suggest that being female is a constant source of empowerment.

Reclaiming traditional markers of femininity is at the heart of this consumption-driven feminist movement, which seems to scream “I’m a feminist, but like, not one of those ugly ones. I wear lipstick!” or, alternatively, “How dare you think my hotness makes me less of a feminist than your lack of hotness?”

Model and actress Emily Ratajkowski has built her brand on this type of feminism. Ratajkowski regularly brings up her feminist credentials in interviews, usually adding that her overt sexuality makes people question whether or not she’s a feminist. “Our society tells women we can’t be, say, sexy and confident and opinionated about politics,” model/actress Emily Ratajkowski wrote for Glamour last year, finally putting an end to the age-old question of whether one can be both hot and a feminist.

But Ratajkowski’s feminism doesn’t often extend far beyond declaring herself — and by extension, her actions — feminist. “A selfie is a sort of interesting way to reclaim the gaze, right? You’re looking at yourself and taking a photo while looking at everyone,” Ratajkowski told Harper’s Bazaarlast year. “When I take nude photographs, I’m not there for the boys. It’s about owning my sexuality and celebrating it,” she said in a 2015 interview with Women’s Wear Daily. Vogue published a listicle last year detailing “all the times Emily Ratajkowski fought the patriarchy,” all of which were, strangely, defenses of her own actions. Embracing empowerment feminism transforms Ratajkowski from a model who happened to star in a music video about non-consensual sex to a feminist icon — while still allowing her to reap the benefits that come with her model status. (This doesn't mean Ratajkowski isn't a feminist, but rather that not everything a self-proclaimed feminist does is automatically a feminist act.)

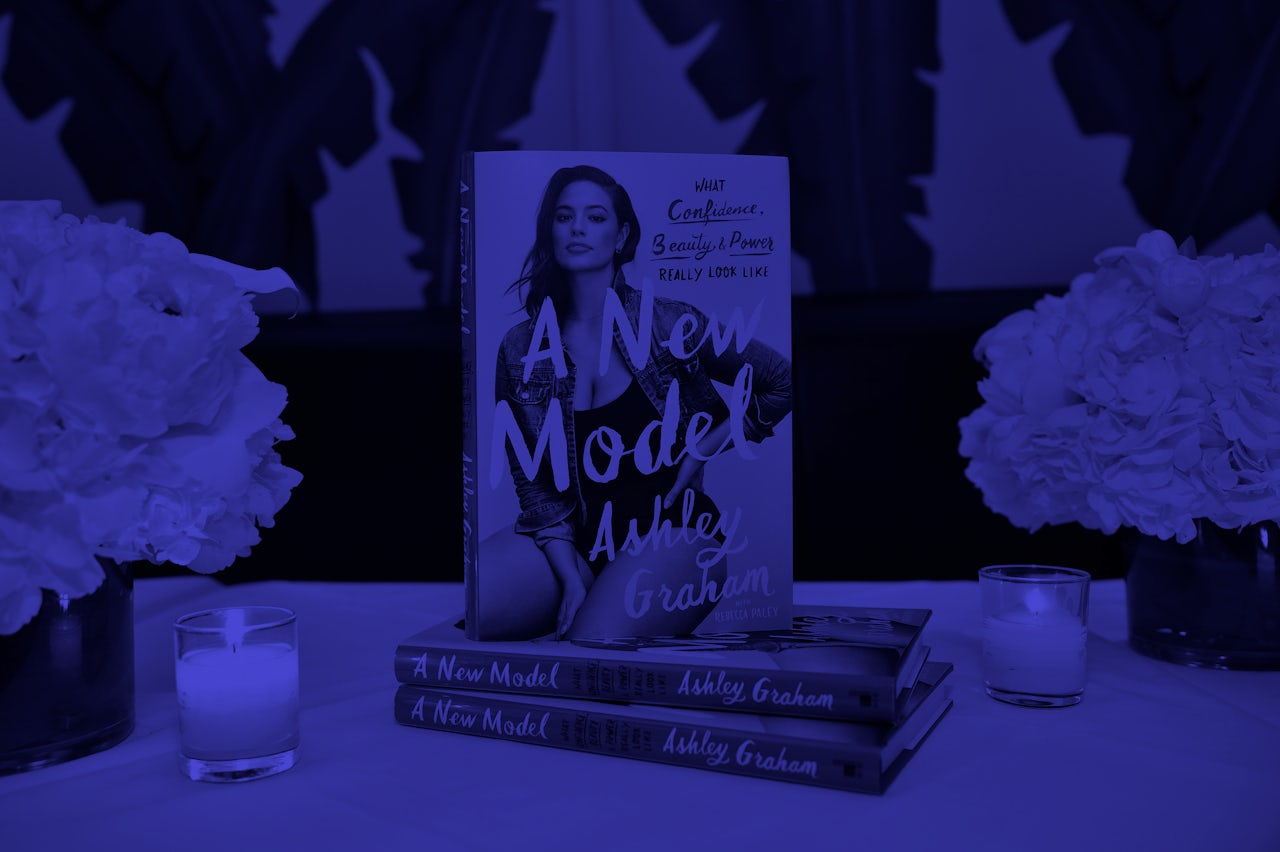

Ashley Graham, whom New York magazine recently called the “first plus-size supermodel” has a similar relationship with feminism. Graham, the first plus-size model to appear on the cover of Vogue, is often heralded as a sign that the fashion industry is becoming more inclusive. But Graham’s inclusion in the supermodel pantheon isn’t putting an end to a culture that objectifies women. If anything, she’s just expanding the category of who gets to be objectified. Graham, too, is profiting off empowerment. She partnered with Swimsuits For All to release her own line of plus-size swimsuits last year, and the brand is so successful it plans on expanding its sizing options to include smaller sizes in the near future. The launch party for Graham's book, A New Model, was sponsored by Lane Bryant.

Much like conscious capitalism, which seeks to reassure first-world consumers that the products they buy are somehow improving the world, empowerment feminism is a movement driven primarily by guilt. Thinking of every purchase as a radical act is a way of absolving yourself of criticism — buying a $15 “FEMINIST” T-shirt from H&M is empowering, even if the shirt itself was made by a woman in a sweatshop. The excuse of “empowerment” can turn even the least ethical purchase into a form of activism.

There’s nothing wrong with wearing lipstick or buying a Kardashian-branded bodysuit because it makes you feel good — but there is nothing revolutionary about it, either.