Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

Few things make me feel as invincible and alive quite like karaoke — namely, when my Creed requests get the top of the queue. Interspersed between the “Jagged Little Pill”-era Alanis, Weezer, and assorted tracks by angsty ‘90s morose female powerhouses like Fiona Apple that I torture my captive audience with, there is always “One Last Breath.” Always.

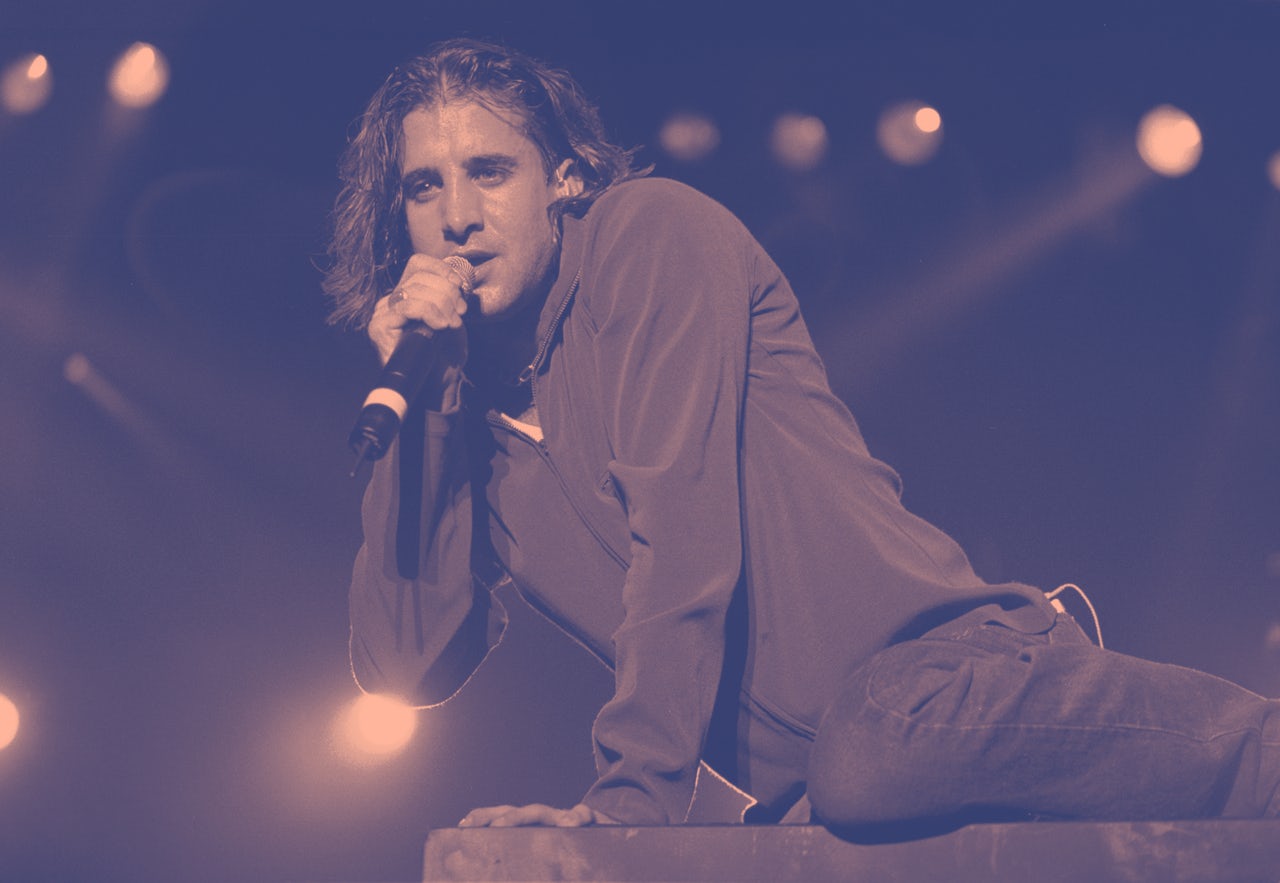

I love Creed. They’re a delicious junk food of a band, a truly guilty pleasure tucked in my most-played Spotify lists amid artists with far more critical acclaim and credibility. Specifically, I can’t get enough of the band’s frontman Scott Stapp, who reached spectacular, undeniable heights of commercial success while also inspiring intense vitriol from vocal haters — and then publicly unraveled. During Creed’s heyday, Stapp became synonymous with Christian rock, as he somewhat resembled Christ himself, long locks flailing as he belted lyrics about overcoming his struggles through faith. Tight tees barely concealed the massive crucifix tattoo on his bicep; beyond that, he had a penchant for extremely shiny shirts, like a plunging, nearly navel-deep lace-up stunner, or this flashy crimson version, and consistently accessorized with copious amounts of man jewelry.

My affinity for a Jesus-tinged band is weird since I’m the reform, mostly-cultural, solely go to temple on the High Holidays, had a Bat Mitzvah, never say no to prosciutto kind of Jewish. But I can’t get enough of anything about cults and extreme religious sects, many focused on Christianity, from Mormon polygamy to Scientology to Jim Jones. Same goes for “hipper,” more slickly packaged interpretations of Christianity: Bieber-vetted, sneakerhead pastors preaching in head-to-toe streetwear, weed churches, The Righteous Gemstones, and megachurches.

Showier displays of faith — religious allegiance telegraphed by big, blingy crucifix necklaces, tattoos of Jesus, or prominently flaunted Bible verses on T-shirts, Instagram bios, Facebook updates, and more — always felt foreign to me. Sure, jewelry shaped like the Star of David and Tree of Life exists: I had a few pendants as a tween, and if you saw Uncut Gems, you might remember Adam Sandler’s chunky, diamond-paved pinky ring. But Jews like Sandler’s Howard Ratner were the exception, not the norm, for how loudly and overtly identifiable one was supposed to be about this particular faith. Judaism isn’t a missionary religion; while actively seeking converts is common in Christianity. Jews don’t proselytize, or at least we’re not supposed to. Plus, converting to Judaism can be notoriously difficult. We are the theological equivalent of playing extremely hard to get during courtship, as Charlotte York’s journey from shiksa to Park Avenue’s Shabbat hostess with the most aptly illustrated.

Even without strong personal ties to Holocaust survivors in my family or life, I’m aware that, no matter how lax or a la carte my own Jewish identity is, my predecessors have had to hide this religious affiliation (or themselves, because of religion) for centuries. By comparison, Christianity’s history is largely unblemished by persecution by comparison. I always wondered what it was like to be the religious mainstream — to exalt your beliefs without that ancestral baggage of persecution.

Ergo my fascination with Christian rock, even the kind that dubiously, emphatically insists it is not Christian rock. Though Creed’s members, including Stapp, repeatedly balked at the Christian rock label, their Christianity was unmistakable. See their Thanksgiving 2001 Dallas Cowboys halftime show, a medley of the band’s best-known bangers accompanied by angel-like shirtless aerial dancers flying overhead and a youth gospel choir (oh, and clips of 9/11 rescue efforts). Or, the lyrics in most of the band’s oeuvre: “Higher” is basically a rumination on heaven, “the place where blind men see,” paved “with golden streets” where Stapp urges us, dear listeners, to “make our escape.”

But the group broke up in 2004, at the peak of Stapp’s drug and alcohol addiction issues, which he later acknowledged was the root cause of Creed dismantling. He technically went solo in 2005 and has put out a handful of albums on his own since, without much success — his most recent album, July’s The Space Between The Shadows, sold 10,000 U.S. copies in the first two or so months of its release. Their 2009 reunion didn’t go anywhere, and by the mid-2010s, Stapp was best known for his erratic behavior. His substance abuse struggles, and mental unraveling surfaced very publicly in 2014 as he enmeshed himself in dozens of conflicting conspiracies, detailed in some 30-odd minutes of videos he filmed and often posted on Facebook.

Rising and falling and rising again, for Stapp, must’ve felt like another part of the story, even when not as many people were paying attention as they once did.

Stapp’s breakdown was uniquely extreme, detailed and vivid, especially given his and Creed’s strong messaging about redemption. Art and life had bled together, in a somewhat sleazy way. The other members of Creed always held to their insistence they were Christians in rock, but at some point — when the checks started clearing, at least — they were just lying to themselves. They were missionaries of a sort, preaching the prosperity gospel with their millions of sales and surprising number of Grammys. Rising and falling and rising again, for Stapp, must’ve felt like another part of the story, even when not as many people were paying attention as they once did.

At least he seems to be doing much better now. He and Jaclyn are not only still together; she’s his co-manager these days. He got sober and took up running; they had another kid, Anthony, in 2018, and now he is even a Little League coach. When I try to imagine this all as one of Creed’s big, gloopy power ballads, suddenly Stapp really does seem a one-man redemption story: the highs of commercial success and fame, the lows of substance abuse issues, and ultimately triumph, even with a few inches less of those Jesus-esque tendrils. It’s a journey befitting all that big Christian energy, and I remain riveted, if not at least ready at karaoke.