Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

As a teenager growing up in Billings, Montana, where the oil refinery injects thick smoke into the sky at all hours of the day, I grew to love extreme art: industrial and noise music, transgressive cinema, anything that would churn my stomach. I voraciously read works by Supervert, Michael Gira, and other scholars of the perverse. I aimed to be disturbed, and like all other edgy teenagers, felt like I could handle anything.

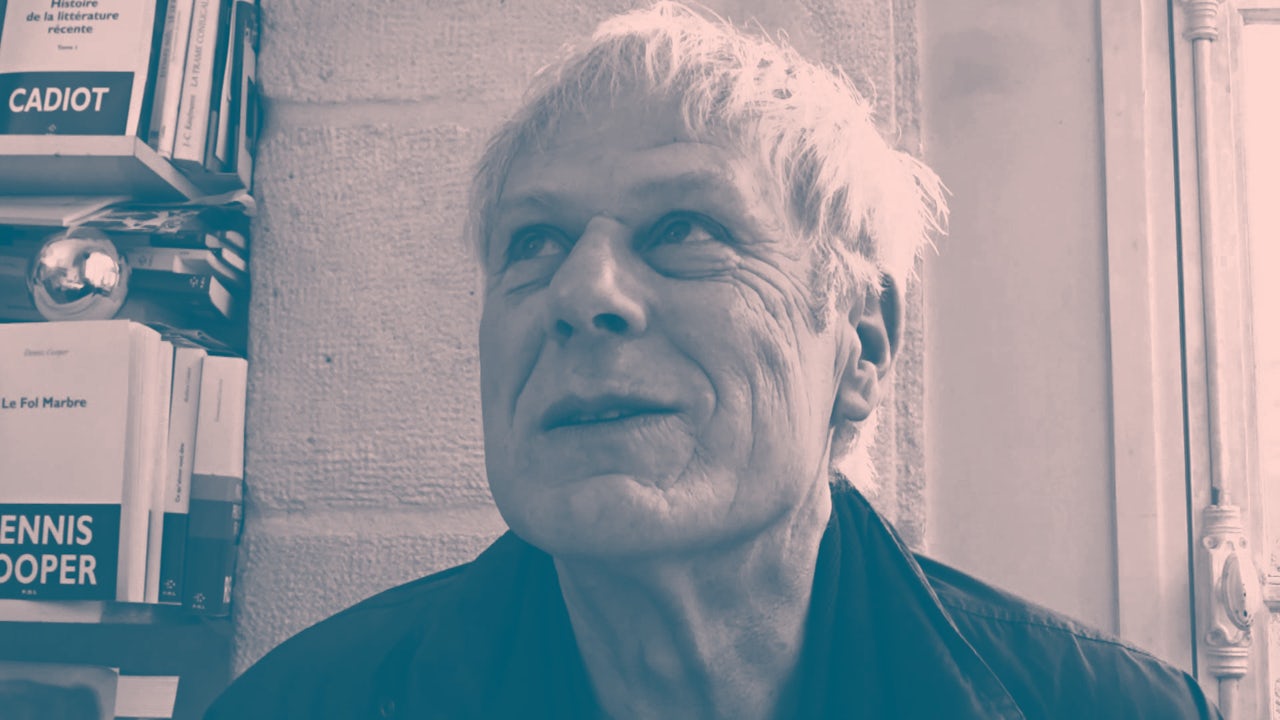

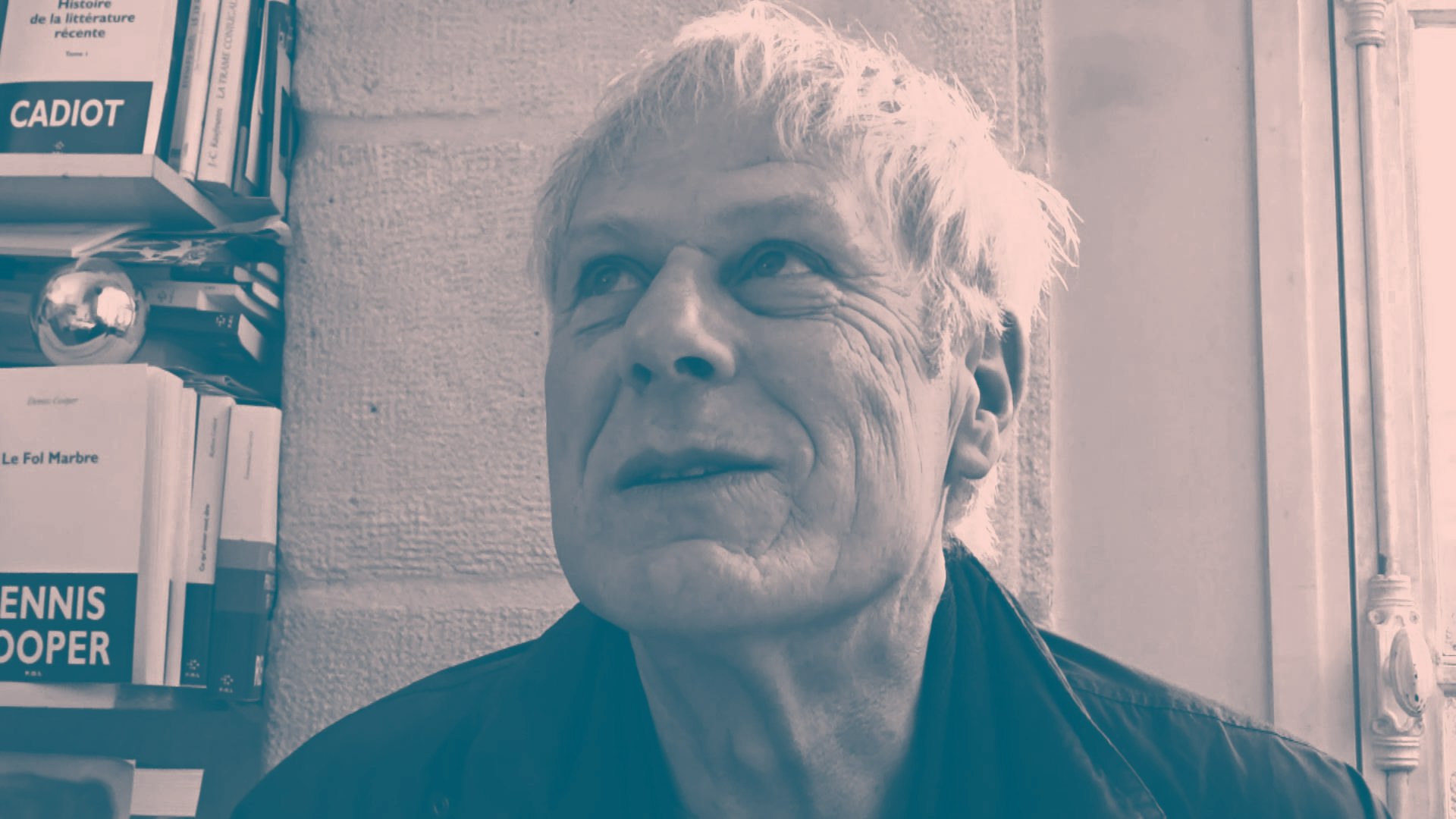

But the writings of Dennis Cooper, first encountered when I was 17, unsettled me before they even resorted to violence. On the advice of a book forum, where I was cautioned about his extremity, I bought a copy of Cooper’s 1991 novel Frisk. I made it about 10 pages before I stopped reading.

The novel opens with a party, where rich teens quaff mysterious pills and engage in mostly anonymous sex. Nothing much happens; two male characters, one heavily intoxicated and fresh out of the bedroom with another guy, exchange phone numbers. Something about the scene, though, was unnerving. There were no murders, no defiling of corpses. It simply felt wrong, simultaneously familiar and otherworldly in a manner more disquieting than any explicit act of perversity. It remained on my e-reader, unfinished and forgotten.

In the years that followed my first attempt at reading Frisk, several things changed: I moved from Billings to Missoula, came out as a trans woman, and lost a good deal of my teenage edginess. My fondness for the grotesque had not disappeared, but I was no longer content to read splatterpunk and gore for gore’s sake. To paraphrase Supervert in his philosophical treatise on deviant sexuality, Perversity Think Tank, the more one explores the perverse, the less perverse it seems. But given how body-centric the queer experience is, doubly so for trans people, there is catharsis in seeing physical forms destroyed.

I didn’t return to Frisk until last month, reading it in two sittings while standing behind the counter at my convenience store job. This time, I got to the expected murder, the necrophilia, and the snuff porn. It was deeply upsetting, of course, but there was a surreal and lyrical quality too. Behind all the gore was something grasping at profundity.

In the six years it took to get back to Frisk, I had not abandoned Cooper. I began religiously following his blog, where he currently posts lengthy screeds about his favorite art and artists nearly every day. His site’s devoted fanbase came out in droves after a previous iteration of the blog, then called The Weaklings, was deleted by Google after it was flagged for containing prohibited content. All of his work was lost, and the deletion sparked a fierce debate about the intersection of the First Amendment and the arts.

His blog was eventually restored on a different host, and is now named DC’s. His mid and year-end lists of favorite books, movies, albums, and art are must-reads for fans of the bizarre and avant garde. He routinely champions and promotes the work of younger writers — Blake Butler, Laura Riding, Ariana Reines, and Grant Maierhofer among them. That’s been part of Cooper’s project from the beginning. Born in Pasadena in 1953, at the age of 23 Cooper founded Little Caesar, a magazine featuring early work by Eileen Myles and Amy Gerstler. His prolific career as a novelist began shortly after. At present, he’s published nine novels, three short story collections, nine poetry collections, two nonfiction works, and four “GIF novels.”

Most of this work focuses on a few key themes: queerness, deviant sexuality, violence, drug use, and overconsumption. The Sluts follows a young escort’s meetup with a client, and details all manner of horrors almost entirely on an escort service message board. God Jr. follows a father whose son was killed in a car accident, and his developing obsession with a building referenced in his son’s journals. The setup is generally simple, a vehicle for Cooper’s characters, who are almost uniformly hedonistic, misanthropic, and dangerous. They kill, eat, and rape each other with a cold aloofness that makes his work all the more revolting.

How much of that violence actually occurs, though, is debatable. Cooper’s work exists in the realm of hyperreality. Toward the end of Frisk, Dennis, the narrator, pens a lengthy letter to his high school boyfriend Julian, describing a series of brutal murders he committed after moving to Amsterdam. When Julian arrives, there is no evidence of any violence, and Dennis eventually admits that the whole thing was a fantasy-driven farce. But the violence’s authenticity isn’t really the point. On one level, his work reflects the limits of language. Cooper’s characters make bold statements only to retract them moments later, like this one, from Closer: “I’m totally evil. I want them to die. I want … I don’t mean any of this.”

On another level, oversaturating readers with grotesque and violent imagery is reflective of the violence regularly committed against queer people. His career took off at the height of the AIDS crisis, and that spectre looms throughout much of his work. Cooper’s characters defile and destroy each other in all manner of heinous acts. His protagonists are largely young and male, having sex with each other one minute and cutting each other open the next. This is done with a reflexive callousness, described in stark and uncompromising detail, mirroring the vicious anti-queer vitriol of the era.

In Cooper’s world, bodies are destroyed for pleasure; in ours, they’re annihilated for profit.

Cooper may not intend it this way. His novels explore deviant desire and meditate on queer bashing, a fuller range of ideas than the ones I’m mentioning here. But throughout my inaugural reading of Frisk, all I could think of were the gays, lesbians and trans people who have been murdered in a manner not dissimilar to protagonist Dennis’s disturbed fantasies. Violence is constantly a threat for queer people; exploring this threat through characters who might be turned on by that prospect makes for immensely compelling reading.

Of course, violence isn’t limited to the physical. Cooper’s characters are both literally and metaphorically deprived of their humanity. They overconsume, whether engaging in wanton sex and drug use with no concern for safety or by actually eating each other. All this excess feels, in a modern reading, like it’s pointing toward the consumption of identity. During the conclusion of this year’s Pride month, a time for brands to signal their support for queer people by plastering rainbows on website headers and profile pictures, it was difficult not to read Cooper through the lens of capital. Queerness is chewed up and repurposed as a marketing tool. Straight people have largely identified the oppressive forces aimed at queers as purely institutional; any positive depiction is, therefore, progress. But having our love, bodies, and sex used to hawk everything from high fashion to Oreos is deeply insidious. In Cooper’s world, bodies are destroyed for pleasure; in ours, they’re annihilated for profit.

The distillation of queer people to sanitized images ready-made for ad copy is probed all the more in his recent series of “.gif novels.” These works are like hellish scrolls through a fucked-up teenager’s Tumblr. Images from anime, video games, and pornography commingle to create something like a short story. In his words, it’s a way of eschewing all the things he doesn’t enjoy about writing prose. It’s a contemporary update of the cut-up works of Burroughs, experimental fiction that’s less psychedelic and more dissociative.

His willingness to probe the darkest recesses of human behavior attracted me to his output, but what makes him compelling isn’t mere transgression. Cooper does not moralize; he presents the actions of his characters, however abhorrent they may be, without judgment. He does something similar on DC’s, where he occasionally compiles escort ads and presents them without comment. They serve as something like proof that the desires he explores aren’t restricted to the realm of fiction.

All this makes his work difficult to recommend to polite company. Even as a fan of his writing, I still struggle through some of his more contemptible passages. The opening scene of Frisk may still be the moment of the book that makes me most uncomfortable, but it was the imagined murder of a child toward the end that I wound up not being able to finish. My instincts cry out for someone to tell me that what’s happening is wrong. I believe that’s the point.