Enzo Traverso, an Italian historian of the Holocaust, said in an intervew last year something that I think about a great deal, which is that there are basically “two antipodal figures that dominate the Jewish world in the first and the second half of the twentieth century: Leon Trotsky, the wandering Jew of world revolution, and Henry Kissinger, the strategist of US imperialism.”

For the bulk of the last 100 years, if the fight for the soul of the Jewish diaspora was between the archetypes of Trotsky and Kissinger, then you could say that Kissinger kicked Trotsky's ass. After all, Stalin had Trotsky killed via ice pick and the Soviet Union collapsed, whereas Kissinger committed and aided genocides, and still lives and circulates among the world’s elites. In fact, he goes to baseball games where is feted by people who are ostensibly tasked with preventing genocide.

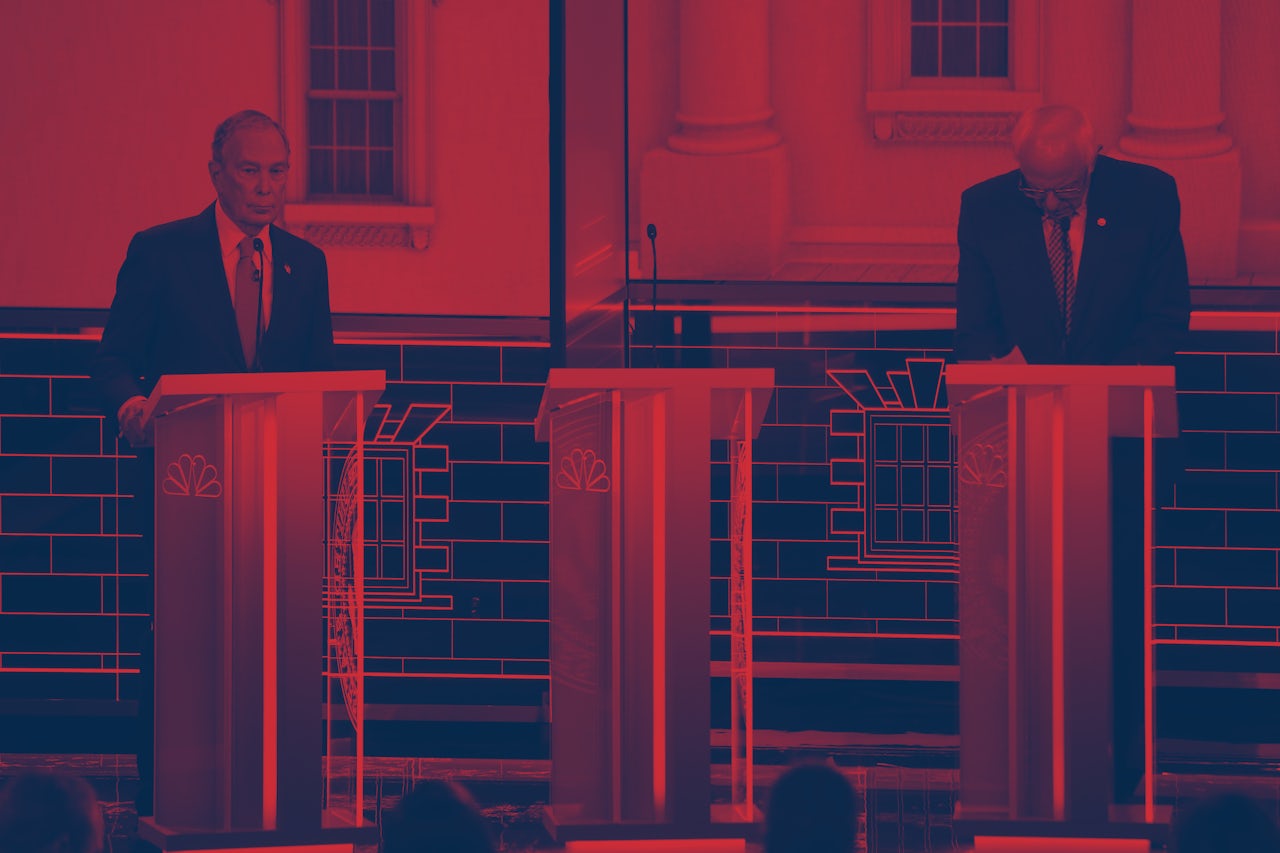

But the spirit of Kissinger is wounded. Its truest avatar in the 2020 presidential race, Mike Bloomberg, billionaire media mogul and the former mayor of New York City, has dropped out. Propelled into the race by his own ego and innumerable riches, the idea was that Bloomberg would right the centrist ship. Amy Klobuchar, Pete Buttigieg, and Joe Biden, so it seemed last November, could not beat back either Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren. After a Tuesday morning blowout, in which Bloomberg’s hundreds of millions only won him American Samoa, the billionaire has bowed out. It’s the wandering Jew who’s won this round.

Born in the Boston suburbs in 1942, less than six months after Sanders was born in New York, Bloomberg’s trajectory has been straightforwardly Kissingerian.

This contrast between Sanders and Bloomberg, the two zaydes, is more than figurative. Born in the Boston suburbs in 1942, less than six months after Sanders was born in New York, Bloomberg’s trajectory has been straightforwardly Kissingerian. Johns Hopkins to Harvard Business School to the investment bank Salomon Brothers to the creation of the financial services behemoth that bears his own name.

In the same way that Kissinger has bounced between Republican and Democratic circles since his time in the Nixon administration, Bloomberg has also shown a propensity to play both sides. Though he taken on the mantle of center-left progressivism in recent years, steering money to climate initiatives and gun control and other liberal causes, Bloomberg was a proud endorsee of George W. Bush back in 2004. When considering Bloomberg’s own history of misogyny and reactionary politics, his campaign seemed to be less about any meaningful liberal agenda he claimed was the goal of his campaign, than an attempt to administer American empire the right way, unlike the excessively blatant Donald Trump.

Sanders cuts as different a figure as one could imagine. Born to a family of impoverished Holocaust survivors, Sanders went from Brooklyn to the University of Chicago, participating in civil rights protests like many Jews of his generation. His “sewer socialist” tenure as the mayor of Burlington, Vermont gave way to a long, lonely period in the House of Representatives and the Senate, where he was a reliable glint of light in an otherwise dark place.

But Jews moved to the suburbs, joined country clubs or started their own, and the work of liberal Jewish politics fell to large establishment institutions reliant on money from donors like Bloomberg.

This contrast between Sanders and Bloomberg does not amount to a statement about the preferences of American Jews (who remain more liberal than the general population), as much as it does about the American Jewish establishment’s political legacy. Though many Jews of Sanders’ generation did participate in the Civil Rights Movement, a similarly large number of them did not. But Jews moved to the suburbs, joined country clubs or started their own, and the work of liberal Jewish politics fell to large establishment institutions like the American Jewish Committee or the American Jewish World Service, institutions reliant on money from donors like Bloomberg.

Of course, humming in the background of all this is the American Jewish establishment’s lockstep support for the Israeli government, a particular enthusiasm shared by Mike Bloomberg, who was the only Democratic contender still in the race to speak in-person at the largest annual Israel lobby conference this week.

Not to extrapolate too heavily from Bloomberg’s loss, but his exit from the presidential race is yet another sign of the weak health of this vision of Jewish politics. The visuals of the two septuagenarian zaydes going to war masks the vastly different constituencies behind them. One is an ancien regime that’s struggling to fill free seats on Birthright trips to Israel, and the other represents something new, a multiracial coalition drawn from the working class and the downwardly mobile middle class — the latter camp being where many young Jews (and young people more generally) reside today.

So now that the battle of the zaydes is over, a realignment has begun. Bloomberg is out of the race, and he has thrown his support behind Joe Biden. And Biden represents another goyische archetype that must be vanquished. Elderly and unconcerned with the urgency of the twin crises of inequality and climate change, the new progressive foe is similarly familiar, your gentile friend’s doddering grandfather. Whereas Sanders vs. Bloomberg was perhaps a test of the direction of the Jews, the more pressing and urgent question about the electorate as a whole is whether they will get behind zayde, or if they’ll open their hearts to... pop-pop.