Maybe Parasite winning Best Picture at Sunday night’s Oscars was a real breakthrough for Korean and global cinema after years of institutional neglect; maybe it wasn’t any of that, but simply the right choice at the right time before we get back to our usual regimen of Green Book-esque winners; maybe it was (lowers sunglasses) the monied Hollywood elite attempting to defang a righteous message about class inequality and prove I totally get it, ha ha, great movie that’s not actually about me by sucking it into their meaningless spectacle.

The Academy Awards are a perfect tableau for this kind of analysis, where cultural events are graded along a scale of Actually Meaningful to Basically Fine to Completely Not Okay. They’re so perfectly engineered to reflect the tastes and anxieties of what remains America’s most desirable cultural elite, even considering the slow disappearance of the monoculture, of the cinema, of taste and attention spans and movies that aren’t in the Marvel Cinematic Universe and so on. Much like the Super Bowl, even people who are completely contemptuous of what they represent are nonetheless curious about what they contain, because it always seems to signify… something.

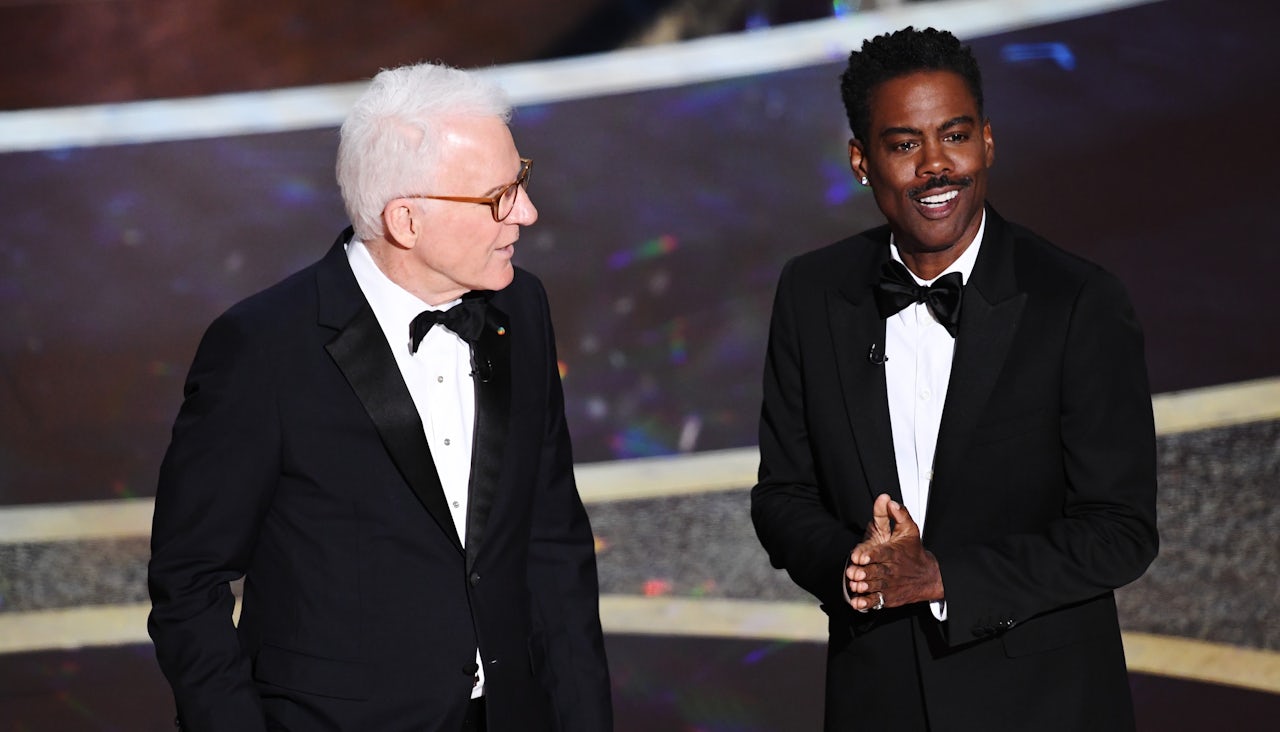

In particular, during last night’s telecast I was attuned to the quantity of references to how the Oscar nominees were so not diverse, ha ha. “Cynthia Erivo did such a great job hiding black people, the Academy got her to hide all the nominees,” Chris Rock said about the Harriet nominee. He and Steve Martin also joked about how no women were nominated for Best Director, and how the Academy had barely upped its numbers of black nominees over a century of ceremonies. “It’s time to come alive, because the Oscars is so white,” Janelle Monae sang during the opening segment, which featured characters and costumes from the diverse movies that weren’t nominated: Us, Dolemite Is My Name, Queen and Slim, and more. (She also said “we celebrate all the women who directed phenomenal films.”) Utkarsh Ambudkar contributed a completely inessential rapped recap of the show to date, including a line about “winners who don’t look like me.”

Aside from that, the producers attempted to bridge this gap by installing a bizarre slate of pre-presenters, mostly non-white, non-male actors like Zazie Beetz, Kelly Marie Tran, and Beanie Feldstein whose job it was to announce the more reconizable presenters. They were so formally second tier that they had to say their own names, because of course the people at home wouldn’t know who they were. All of this amounted to a nervous chuckle: It’s true, the Oscars are pretty white and male, just as they often are, but we’re aware of it so don’t make too much of a fuss… okay? Please?

It’s easy to see this as a defense against Twitter, whose marshaled political sensibility forced the literal cancellation of one Oscar host, and created a hashtag that did a lot to raise awareness of the Academy’s demographic imbalance, though whether it solved anything is clearly up for debate. Still, these winking references didn’t exactly excuse the Academy’s oversights, which critics of any ideological pole could point out. It’s hard to believe Hollywood’s attempts to address systemic sexual violence when its In Memoriam segment uncritically honored Kirk Douglas and Kobe Bryant, two men who were accused of sexual assault. We can also dig past the lack of black nominees to point out that Parasite was the first Best Picture winner to receive no acting nominations since 2009’s Slumdog Millionaire, another movie starring Asians.

But you wouldn’t find any references to this during the ceremony, because it wouldn’t be rudely funny — it would just be rude. Power shrinks from specificity; as anyone who follows politics knows, it’s much easier to throw your hands up at the big problem and go that’s a big problem than to actually do anything about it. And while I say this with the full caveat that the Academy Awards are mostly attended by unserious people who love attention — shout out to Anthony Hopkins and Joe Pesci, both nominated for awards and both not in attendance — there are more creative, effective ways to show dissent than by gesturing at it. Imagine, for example, if a coalition of the nominees and award winners agreed not to show up out of protest, and publicly explained why. That would be far more effective and attention-grabbing than stitching some names on your expensive dress.

Then again, the Academy Awards are not a vehicle of social transgression, and it would be truly naive to expect this. So if we are to make a sweeping cultural declaration, it’s not that these ceremonies are populated by hypocrites (though they are) or that the Oscars can’t fix everything through the magic of cinema (though they obviously can’t). It’s just that the entire song-and-dance demonstrates how joking about a problem isn’t really fixing a problem. In fact, it might even be worse, because if you know something is a problem, and have some small power to fix the problem, but choose not to use it, then you’re just the smartest, most useless person in the room. What use is your arch understanding of the situation, when it continues to endure — when that arch understanding has been implicitly condoned by the powers that be?

I don’t expect Steve Martin and Chris Rock to use their free time advocating for structural change at the Academy, because I know they have lives, and also it’s probably super fun to be rich as hell. But here their uselessness becomes its own message as the limitations of awareness, one of liberalism’s greatest buzzwords, are laid clear. In this small, depressing way, the Oscars finally have something to impart.