but this place is just right.

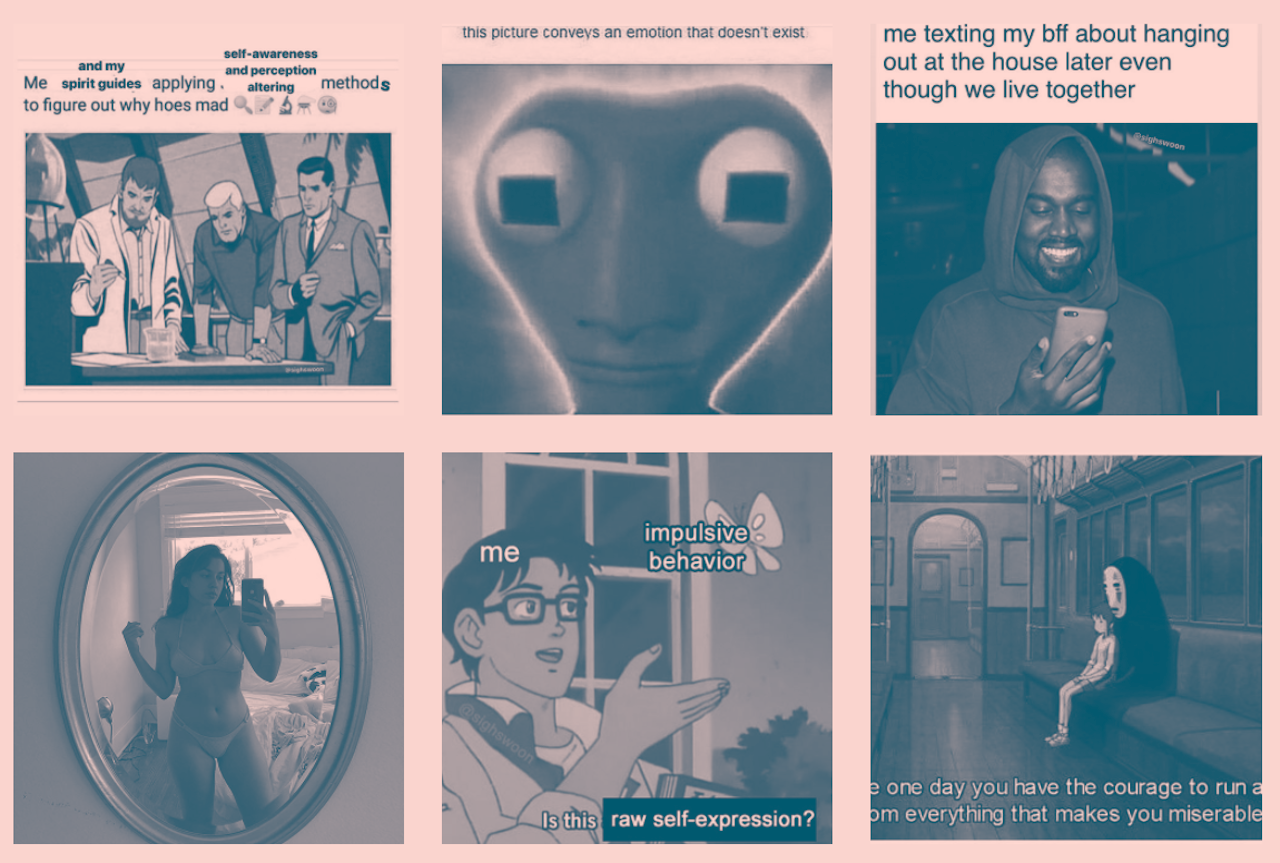

If you’re lucky enough to stumble upon Gabi Abrão’s enchanted Instagram account @sighswoon, you may feel as though you’ve unwittingly entered an existential funhouse of familiar thoughts. The account reflects and refracts particular beams of internet visions, blending into a meme-scape made of the lo-fi internet aesthetic to which online audiences have grown accustomed. It showcases oil paintings and grumpy chiuauas and photos of Abrão in thrift store dresses. There are screenshots of texts messages with your Higher Self and memes of Penelope Cruz realizing things in varying emotional states.

When I first came across the account, I felt as though a mirror had been held up to own latent feelings and half-epiphanies about social media, selfhood, and creativity. Abrão’s how-to guides on topics such as How to Embrace Your Shape-Shifting and Ever-Changing Nature (a guide to the non-fixed self), Things You Can Pretend to be When You Feel Uncentered (a lush, self-sustaining island or a cat napping in the sunlight are instructive, she writes in the post), and How to Have a Positive Experience on Instagram (the mute feature is magic) are genuinely useful in an age where it seems like personal branding is a fact of existence.

The specificity of Abrão’s descriptions of being a human on the internet is what sets @sighswoon apart from a crowded landscape of Instagram creators. Like most successful meme accounts, there’s a deep relatability to her content. But perhaps unlike most meme accounts, the voice behind that relatability is self-reflexive, writerly, and skeptical of her own likable illusion. “I’m not your woke bae or eternal sun,” she wrote in a post reflecting on the gap between content creators and consumers. “I do stuff and learn lessons and live like every other 25-year-old girl. I just meme and write about it publicly.”

In September, Abrão posted a video of herself attempting to destroy a magic eight-ball. Inspired by Alejandro Jodorowsky’s psychomagical belief that undertaking “poetic acts” can alter the mind’s perception of reality, she tries smashing it with a hammer, wedging it open with a screwdriver, and even burning it with fire. Eventually she pierces through the plastic to retrieve the small die floating in murky blue liquid, each icosahedron edge revealing an alternate fortune. “I was tired of imagining my fate was determined by something other than myself and my environment,” the caption read.

Attachment to external signifiers is @sighswoon’s favorite nemesis. Recently, she made a 30-minute video about why she gave up astrology. In one of my favorite posts, Abrão photoshopped her ex-boyfriend out of a picture of them together at Disneyworld. In his place is nothing but a figure made of puffy white clouds against a blue sky. “Relationship status: A tumultuous yet satisfying open partnership with the ether.” She invited her followers share their own photoshopped ex photos; the submissions are as heart-hurting as they are funny.

In her 1966 essay “Against Interpretation,” Susan Sontag wonders if film is one of the few modern artforms that has escaped over-intellectualization “in part due simply to the newness of cinema as an art.” Sontag laments the “mucking about” of her contemporaries, who insist on digging behind art for a corresponding metaphor to make sense of it. She criticizes the neatness of this act: how audiences can cling to prescriptive meaning without experiencing the sensual knowledge of what’s right in front of them. “For such a long time [films] were just movies; in other words, that they were understood to be part of mass, as opposed to high culture, and were left alone by most people with minds.”

The same might be said of social media personalities in 2019. It’s been about five years since the alluring grips of the algorithm have sucked in and churned out people into smooth archetypes of themselves. The glossy veneer has grown tiresome. The samey interests, weddings, color palettes, vacations; even the bleary-eyed “getting real” selfies adhere to a prefabricated set of steps. The lifestyle influencer occupies such a fraught position in today’s cultural discourse because she inundates us daily with a flattened experience we’re meant to aspire to. If Instagram is performance art, the truth is most of it is not very good. (And while Instagram and the art world have intersected plenty, the term “influencer-artist” has only grown pricklier over time.)

This is not to say that an Instagram account is unworthy of artistic consideration, however. Like film in the ’60s, Instagram’s newness (and the volume of content it holds) sometimes tricks us into overlooking its cultural value. That so many of us are adept at creating on Instagram has made it difficult to distinguish between someone who has a genuinely interesting perspective and someone who’s good at performing “interesting” on Instagram. Is there a difference?

“Perhaps the way one tells how alive a particular art form is, is by the latitude it gives for making mistakes in it, and still being good,” Sontag wrote. The mechanics of the Instagram feed don’t allow for much latitude. If you take a step outside its set choreography, most of the time your work just won’t be seen. But some of the most dazzling (and successful) Instagram artists have been able to harness the constraints of the algorithm to create work that jolts you.

The shapeshifting artist Amalia Ulman, for example, embodied multiple fictional personalities on Instagram in 2014 in her project, “Excellences and Perfections.” Ulman performed the online aesthetics of a cutesy LA “It Girl” (often sneaking into upscale hotels and restaurants to take photos for her feed), a sexed-up sugar-baby, and a faux-spiritual wellness influencer with unsettling accuracy. In content, Ulman was doing what we all do: bending the contours of our own image to create something more exciting on the Internet. But Ulman played her role as influencer with such profound exaggeration at such an accelerated pace, the absurdity it revealed was louder than usual.

Shapeshifting is a recurring theme in @sighswoon’s online presence, too. Abrão sells totes and crewneck sweatshirts embellished with, “The cyborg in me recognizes the cyborg in you,” and she has cited Donna Haraway’s feminist essay, “The Cyborg Manifesto” as an influence. Part machine, part human, Haraway’s cyborg is a fusion of partial identities who blurs divisions through her transcendence of them. The cyborg exists in an imperfect world — one defined by the constricting dualities of human/robot, male/female, us/other — but because of her engineered versatility, she moves powerfully and fluidly through it in ways the mortal world can’t comprehend.

With over 100,000 followers, partnership posts with fashion brands like Hara and The Great Eros, and brand-tagged shopping roundups, Abrão certainly seems to be part influencer. At the same time, @sighswoon’s content publicly grapples with pillars of its own existence within the influencer economy: interrogating the value of visibility, fixed traits, consistent aesthetics, monetizability. Social media isn’t the first place and likely won’t be the last where artists negotiate their creative practice with their need to make money.

Like any cyborg, Abrão is aware of her own powerful contradiction. Here is @sighswoon playing to the tune of the algorithm and our culture’s fetishization of the female form (and in ad form, no less), and here is an inexplicably wholesome photo of Abrão's crotch in a fluorescent bathing suit. While today it seems like influencers only guide us down a dotted line of how we should aspire to feel, buy, and live, @sighswoon offers something more murky.

When I reached out to Abrão while writing this piece, she kindly declined my request for an interview. She didn’t cite a scheduling issue or a conflict of interest, but instead told me that there are some ideas she’s working with that she doesn’t feel comfortable putting into words just yet. The gesture reminded me of Barbara Kruger speaking about her own art in 2014: “One of the great joys of being able to project your subjectivity into an image or an object or a building means you don’t have to be there physically. You don’t have to be the face of your work.”

Without exacting descriptions from the person behind @sighswoon or a digital avatar reliably turning herself inside out to me, I had no other choice but to turn to the work itself. What I found was a soup of ambivalent imagery and text that’s hard to capture with words alone. There was so much to interpret, but interpretation failed me.

I suppose that’s the thing about cyborgs. It’s rare, if you find them, that they’ll speak with you directly. Instead, recognizing the cyborg in you, they ask you to feel for yourself.