but this place is just right.

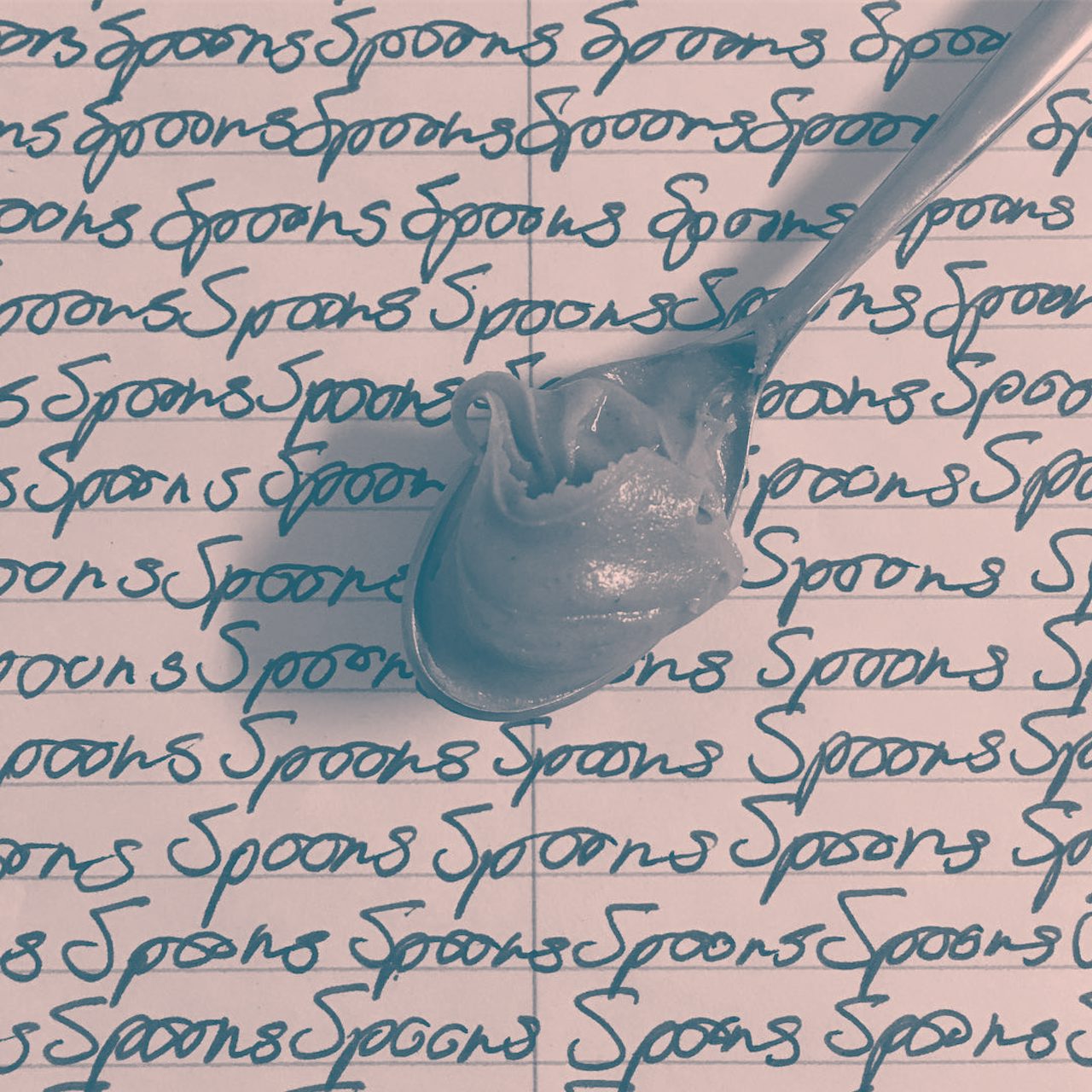

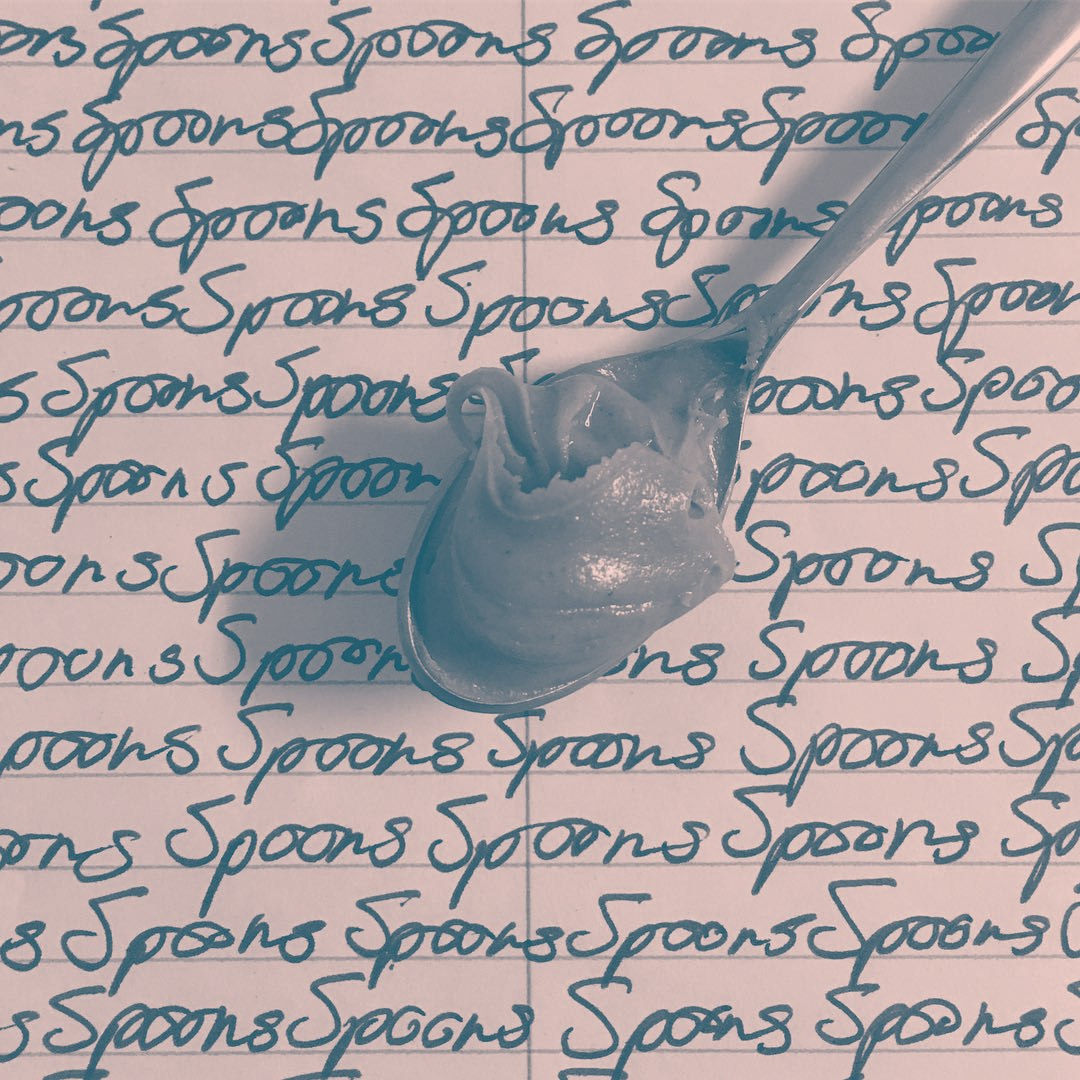

In March of this year, a small manilla package arrived in my mailbox via air mail from Edmonton, Alberta, Canada. Conspicuously, my name was absent from the post. Instead, it was addressed to my Instagram handle. On the customs label affixed to the package, under the itemized list of contents, it simply read, in delicate script: Spoon.

Cruise your internet explorer of choice over to the Instagram page @arden.angley to see the origin of the spoon, and the artist’s performative obsession over the utensil. One of my favorite things about Instagram is finding users who break the expectations of the form, transforming an image-sharing app into something beyond the single image. No doubt that @arden.angley succeeds, and does so through creating something ritualistic, peaceful, and bizarre in its banality. Here we have the notion of single-serving blogs, manifested into single-serving reality, quite literally: a spoonful of peanut butter, in a photo. That’s it. That’s the blog. Please feed me.

A few years back, I was a daily contributor for what was then called the Art and Design channel at a major music and lifestyle publication. Part of my responsibilities included keeping apprised of, and searching out, odd or extravagant or inspirational Instagram accounts. The purpose served the publication of the next, ever-looming listicle: “50 Instagram Photographers Who Will Blow Your Mind!” or “Check Out These 25 Photographers Under 25 Years Old!” or “The Top 10 Fucking Best Instagram Photographers You Must Fucking Follow Right Fucking Now!” You get the point. Often, this went as smoothly as finding a grip of photographers with fewer than 1,000 followers whose aesthetics I agreed with on a gut level. The pace of my work did not allow for much critical reflection, as I wrote close to 900 articles (five a day, give or take) for this publication in about six months.

This alcohol-and-caffeine-fueled fever dream broke my egalitarian belief in the Internet. Because the goal stood, honestly, not to illuminate the work of marginal artists. The goal stood to forcibly affiliate marginal artists to the relentlessly assertive lifestyle brand in real time. Instagram photographers gratified the prime directive of my job description (content! content! content!) because photography manifests as excision of space from time, in visual form. The contemplation and execution of the art practice exists far away from the post itself. In other words: photographers, in particular, made my work more comfortable, by doing the heavy lifting for me. If you trust a photographer, you trust their technical ability in the context of their eye for beauty, truth, or a combination of both. It’s easy to parse the aesthetics of photography without any critical reflection whatsoever: input/output, yes or no. My posts on their posts were a shining example of the confirmation bias machine of the internet hard at work.

My cynicism, here, now, manifests as shame turned backward. I’m not saying anyone I wrote about did not deserve to be written about. I’d suggest, rather, that the breakneck pace of such a blogging job constrained my purview to instantaneous aesthetics. Durational projects had no place in the confirmation bias the internet seeks to reinforce. If I had written about Arden, simply including one photo of one spoon in a larger list of nice-looking photos from a semi-randomly selected list of nice-looking Instagram accounts, would that have been representative of the project whatsoever? I submit that it would not.

Though Canadian, Arden possesses a perfect understanding of the nihilism immutable to our moment. On November 8, 2016 — Election Day — the account posted an empty spoon. The next post, on November 10, 2016, disrupted the pattern Arden set up for weeks, simply by repositioning the spoon in the frame. First, the utensil jutted from the bottom left into the center. Now, and since the election of Trump, the spoon has interceded from the top right, implying an inverted perception of reality, to that which we had previously conceived. There is no escape from this upside-down nightmare. There is only how we frame it.

There are two things to consider, here, in the critical evaluation of Arden’s project: 1) peanut butter, and 2) spoons.

The American folklore of the peanut, as with much American folklore in regard to truth, reframes the history of peanut butter as explicitly “American.” Which is true, in that the legume in question (the peanut is not technically a nut) originates from South America. The Aztecs and Incas get credit, in alternative histories, for the first-known iteration of peanut butter. It is surmised, through recorded development in language, that Portugese imperialists helped the plant spread through Northern Africa and the Middle East and Asia, where it found a welcome home among Chinese and Thai cuisine.

Accelerated developments in peanut processing coincided with the American Industrial Revolution — yet a Canadian, Marcellus Gilmore Edson, first patented peanut paste, in 1884. History consistently miscredits George Washington Carver, an American advocate of the versatility of the peanut, as the “inventor” of peanut butter. Looking back, he seems to have been a dilettante with a freakish obsession with not just peanuts, but also sweet potatoes, soy beans, and pecans. Even in light of Carver’s contributions to the world of peanuts, I’d call him an artist before anything else. His higher education kicked off in music and illustration, which led him to drawing plants, which led him to botany. As he ascended into leadership positions as a botanist and plant pathologist, his fixation became expanding the usage of the aforementioned crops. He is the first African-American to have a national monument dedicated to him.

Yet again, there does seem to be a certain Amercian Exceptionalism to peanut butter. Consider the National Peanut Board’s claim that the average European eats less than a tablespoon of peanut butter a year, while Americans cumulatively eat enough to “coat the floor of the Grand Canyon.” An impossible statistic! And yet it is on the “fun facts” page of the National Peanut Board’s website.

Onto spoons. In the 1760s, the Irish poet Oliver Goldsmith wrote a phrase which commonly gets truncated into a condemnation of privilege: ”One man is born with a silver spoon in his mouth, and another with a wooden ladle.” The second part of this idiom rarely gets relayed, but with the context it adds, suddenly we see the material conditions of inheritance disrupted by a spiritual meditation on equilibrium and coveting. For what difference does it make, having the silver spoon or the wooden ladle, if neither person has a bowl of soup before them? The virtues of a “spoon” rarely extend to the material itself. Further, the etymology of “spoon” (Old Norse) derives specifically from wood. The silversmiths are liars. Privilege is bullshit. A spoon is a fork with more surface area. A spoon is a knife with more opportunity, less intention. A spoon is a bowl, a shovel, a cradle, a net, a pool. If it can’t be done with a spoon, is it worth doing at all?

It is easy, and perhaps preferred, to spread peanut butter onto a slice of bread with a spoon. The concave side acts as vessel. The convex side acts as distributor. Only the bold will choose “spoon” over “knife” in the war of sandwich making. But those are the Edsons and Carvers of the world, those who look at a peanut and see a jar of protein paste, who look at a spoon and see the ideal object with which to spread it on bread. That’s the internet, in a nutshell: nothing is as it seems. I know nothing about @arden.angley. But I know Arden Angley mailed me a spoon. And that’s the “heavy lifting” I was referring to earlier: the lightness of a single post distracts from the soothing wholeness of Arden’s project. What may have started as a curiosity developed into a ritual, a practice, an exploration of comfort. And we must remember: these are photos. The project expands because of the obvious, endless, inventive spirit demanded by such artistic constraints as “take a photo of a spoonful of peanut butter.”

As someone who became addicted to the internet and social media over the last decade, it made me uncomfortable when Arden skipped a post, though it’s incredibly self-centered of me to not imagine a life for this benevolent spoon deity beyond the frame of Instagram. Arden’s practice brings me comfort, because it shows the audacious potential of humankind stretched to the limits. Comfort is not an amenity, or even a luxury. Comfort derives from reliability of a circumstance. We become addicted to comfort. We find comfort in addiction because addiction becomes reliable. The cycle perpetuates through delusions of necessity: I do not need Arden’s posts, but I think I do anyway. But the greatest comfort derives from the reliability of the self. Siddhartha achieved enlightenment not because of the ascetic conditions of the hero’s journey, but from the truth manifested from within. And here is the truth: there is no spoon — until the spoon is mailed to you.