but this place is just right.

In the wee hours of September 4, as the world was burning, Brits were contemplating a swift Brexit and Americans were bracing for a hurricane, my favorite Twitter account, @PastPostcard, shared an arresting tweet: A photo of two people in a tiny red tram, high above an alpine valley, with the words “I shall bring the sausage.”

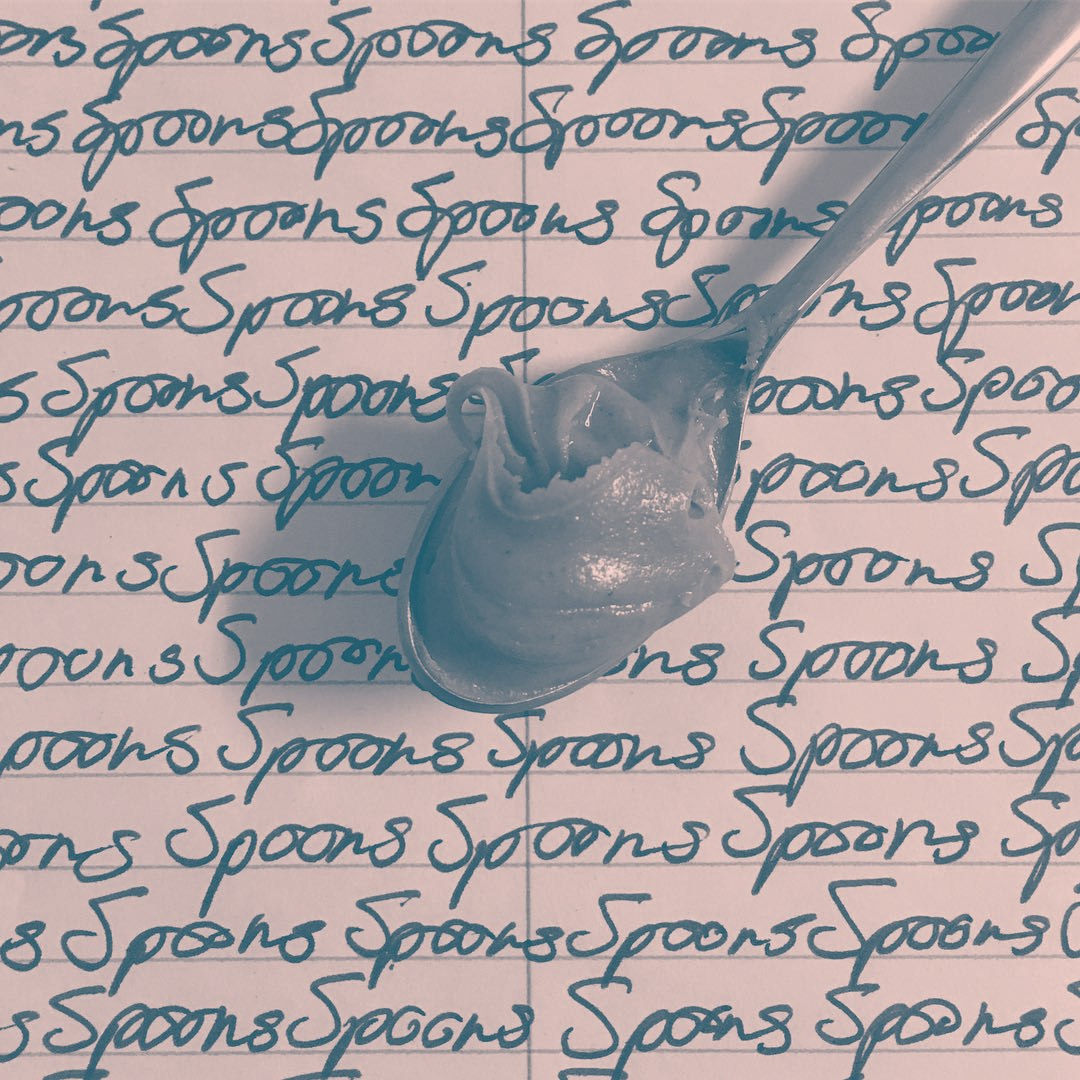

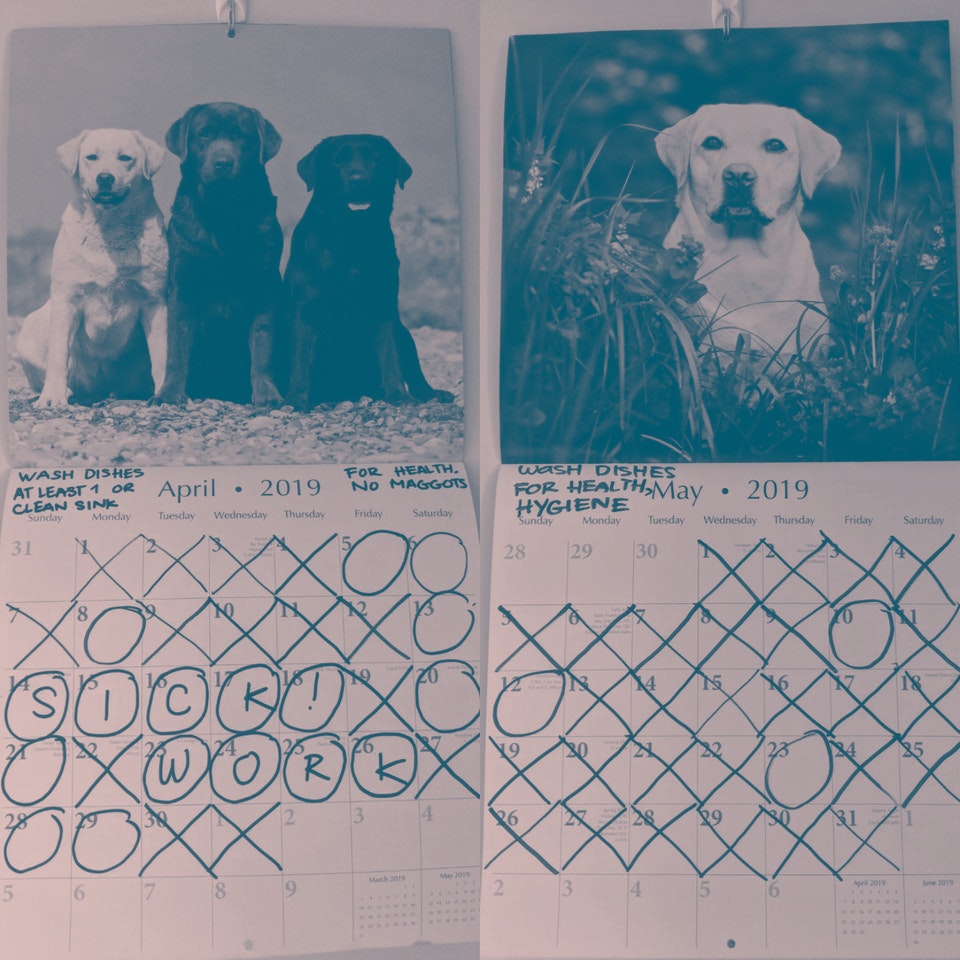

Tom Jackson, a director of television commercials in London, created the Postcard From the Past project in 2016. His cardboard empire now includes a book and a podcast, but it’s best known for little social media moments like these. In an otherwise apocalyptic newsfeed, followers find lovely vintage photographs of England, alongside completely incongruous lines pulled from the correspondence on the back. Many of the posts are relatable in their dreariness, like an image of an abbey with the understated caption “The thought of work — offputting.” Others are in all-caps, the written equivalent of a guttural scream, like a blurry picture of Christian art beneath the query, “WOULD GOD REALLY TELL US TO LOVE OUR ENEMIES — THEN HAVE HIS SLOW ROASTED FOR EVER IN HELL?” But my favorites are delightfully rude, like a serene image of a pasture juxtaposed with the absolutely sick burn, “Elizabeth’s ear has continued to be a real pain — to everybody.”

Elizabeth’s ear has continued to be a real pain - to everybody. pic.twitter.com/EvmGeNJYOT

— PostcardFromThePast (@PastPostcard) August 21, 2019

The project began when Jackson, who collects postcards in his free time, made a few acquisitions online. The century-old curios arrived stuffed between more recent postcards — throwaways from the ’70s inserted into the envelope to ensure nothing got bent out of shape in the mail. Jackson noticed the surplus cards had messages on them. Boring ones, but conceptually interesting messages nonetheless. “So I started buying cards from this era, from the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s in some numbers,” Jackson said. (He describes his methodology as “Flick, flick, flick, flick — oh, fantastic…”) Now, Jackson has roughly 70,000 postcards from this period filling his garage, and just as many Twitter followers, all reveling in the grotesque display of feeling tucked behind the perfect picture.

In the age of instant messaging, sending a postcard feels like quite the undertaking, and looking at them online is a reminder of another time. On the rare occasion I actually get one all the way to the post office, I feel the warm glow of good manners. In three to five business days, the recipient will have physical evidence of my moral character. But those notions are apparently misplaced: In an episode of the podcast Ologies, host Alie Ward relays the story of noted prankster Theodore Hook, who invented the form in 1840 when he sent himself a garish hand-painted caricature of British postal workers. Hardly the sentimental origin story I’d anticipated, but postcards made long-distance communication so cheap and easy, they took off nonetheless.

Jackson’s private postcard collection draws mostly from the Golden Age of postcards, the period between 1900 and the start of World War I when people sent them by the billions. But his Twitter account focuses on what he calls the postcard’s Silver Age. Starting in the 1960s, millions of working- and middle-class people in the United States and the United Kingdom discovered vacationing. Companies and city governments were eager to advertise their tourism destinations, and images of the Hollywood Bowl or Manchester seascapes sent on another person’s dime were a great way to spread the word. In return, consumers got a miniature billboard for their experiences — a place to describe, however briefly, what they saw and how they felt about it.

To keep @PastPostcard (and his other, smaller accounts, @AmericaPostcard and @DreamPostcard) replenished, Jackson keeps a pile of cards with him at all times. When he has a few free moments at home or at work, he scans an image and uploads it with a select line. Over time, Jackson has come to see the account as an ongoing art project or an extended essay on 20th century life. “[I] don’t explain them, don’t put them in quotation marks, don’t say where the card comes from, don’t put the date,” he says. That way, “it’s as fresh as when it landed on someone’s doorstep.”

Jackson’s contextless approach has earned him a lot of fans. Something similar accounts like SovietPostcards or the NYPL Postcard Bot, which is bogged down by names, dates, and links, can’t claim. Most of his followers seem to understand his mission, he says. Interestingly, though, I noticed that a lot of emotional historians — people who study the way emotions change over time — follow the account.

Jennifer Wallis, who studies the history of medicine and psychiatry at Imperial College London, says she follows the account purely for its entertainment value. “The ones complaining about holidays are always amusing, but I also enjoy those cards where the image and text seem so at odds with each other,” she wrote in an email. “There was a recent card that was a photo of a sink plughole clogged with hair (can’t imagine why a company or place would produce this) and the news that ‘Annie got married last Saturday.’ I often find myself wanting to read the rest of the card when it comes to examples like that: Was Annie the writer's nemesis? Had they chosen an unpleasant card specially to relate that news?”

Annie got married last Saturday. pic.twitter.com/kY8Kedw4Xr

— PostcardFromThePast (@PastPostcard) August 30, 2019

Susan Matt, a professor at Weber State University, says postcards can be useful in emotional history research. “What really guides our history is what people are feeling,” she says. Newspapers and magazines can reveal the “feeling rules” of a society — how we’re supposed to perceive and react to different situations. But letters, diaries, and postcards show the messy reality — our real response to Elizabeth’s annoying earache, or the thought of returning to work on Monday.

I asked Matt about one of the most common @PastPostcard themes: complaint. Zippers break, scooters break, hearts break. “I got stuck in my deckchair” reads a card covered in flowers. “Beaucoup de vomit” says another, this one of a shepherd leading his flock up a hill. Matt speculates that some of these asides are an attempt to ward off envy on the part of the recipient. “Maybe the ‘I’m miserable,’ is a way to soften the brag” of traveling, she says. Yes, this beach is beautiful, but I assure you, it’s killing me. Whether it worked at the time or not is unclear. But for Twitter followers, reading a stranger try to soften the blow of a trip to Ibiza decades ago is undeniably amusing.

Just like a postcard, there’s a flipside to Jackson’s deracinated approach. “I do get one or two followers who think I’m singing a hymn to colonial Britain or something and I slightly despair,” he says. But Jackson’s not interested in nostalgia. In fact, he tells me, he’s “allergic to it — I think it���s dangerous.” That might seem strange coming from a dedicated deltiologist (the technical term for someone who collects postcards), but Jackson says the postcard’s “job is to surprise you.” He sees @PastPostcard as a reminder that “the past is not as knowable as people who trade in nostalgia like to think… [and] it’s not something you should readily crave.” People are about as funny, rude, and loving as they always were.

On a recent trip to New Mexico, I saw postcards everywhere. I bought them as I always do, to stuff in notebooks and pin to my wall. I selected an illustration of Bandelier National Monument and a lenticular image from a local art collective. This time, though, I successfully sent three of these postcards to friends and family. The Albuquerque post office’s automated processing mark obscured my opening words, and I appear to have arrived home before the letters actually reached their destinations. But even still, my grandma Facebook messaged me to say how much she appreciated hers.