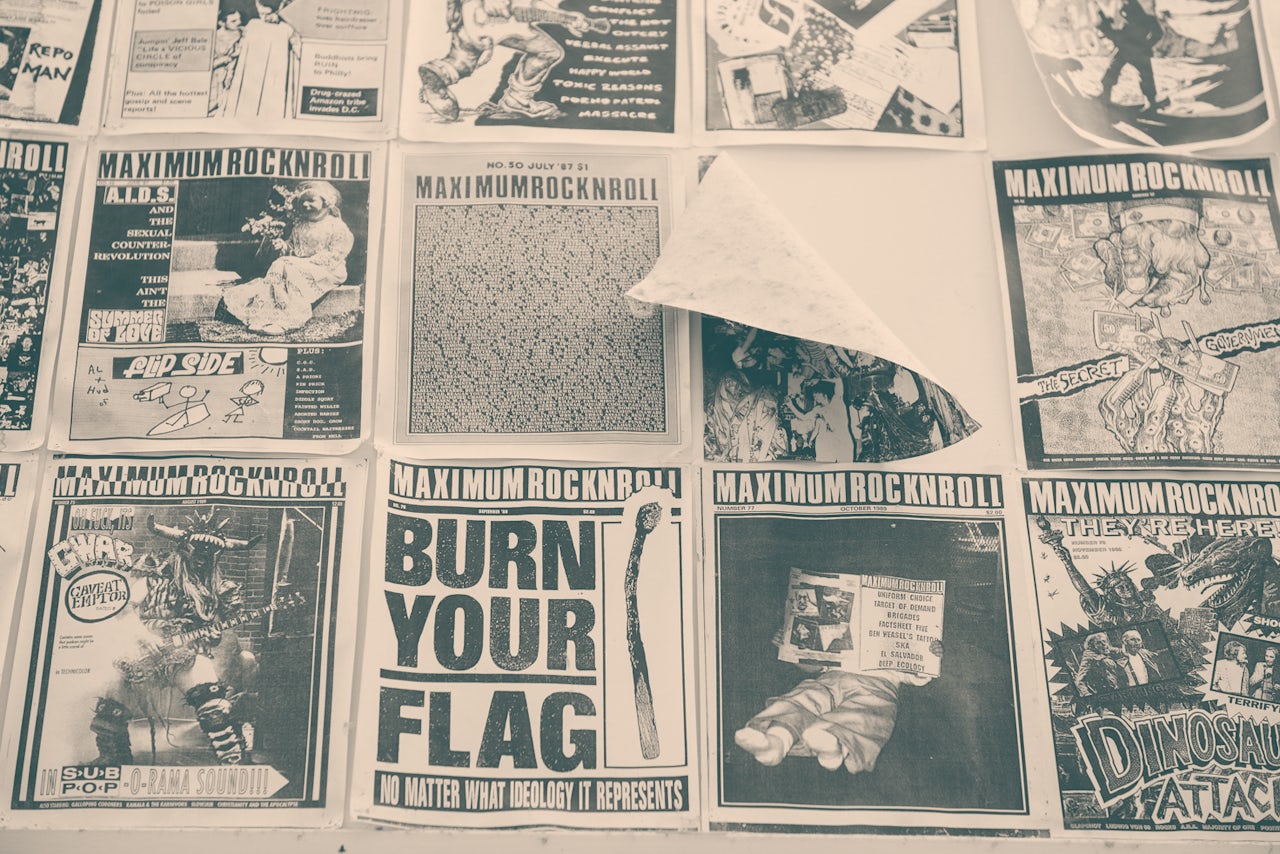

Amid old cymbals, bikes, and back-issues, 55,000 punk records lined the industrial garage of endangered punk magazine Maximum RocknRoll’s San Francisco headquarters, packed carefully in austere white boxes stacked four high. Each crate was numbered and organized alphabetically by absurd, occasionally recognizable band name: Box 63 had Disorder through DOA; Box 159, Pennywise through Phantom Head; Box 103, Human Error through Hüsker Dü. “This is what happens when a bunch of anarchist punks try to run a business,” Maximum RocknRoll editor Grace Ambrose sighed, staring at the collection.

Inside the building, known as “The Compound,” a dizzying mix of priceless punk artifacts, obsolete office equipment, and useless junk exploded out of every possible orifice: a jar jammed full of illegible receipts; kitchen drawers bursting with unfilled water balloons, ethernet cables, and user manuals for long-broken Cuisinart appliances; chairs piled with staplers and tape dispensers; walls papered with show posters and political manifestos; a Slayer skateboard.

The squat brick structure sits on an increasingly-trendy block of San Francisco’s NOPA neighborhood, nestled between multi-million-dollar Victorians, a 3-month-old tapas restaurant, and a boutique marijuana dispensary. It’s unassuming; the only external indications of The Compound’s true identity are the decorative records hanging in its windows and the occasional legendary garage sale.

But since 1982, MRR has chronicled, criticized, and catalyzed the punk movement via its independently-produced, globally-distributed zine. Now, facing the most expensive rent prices in the country, on top of all the ominous trends in media you’ve read about, MRR must at long last shut down its print operation and vacate The Compound, where its volunteer “content coordinators” have produced its 100-page-plus monthly issues and lived rent-free in lieu of earning a salary since the ‘90s.

It was mid-March: move-out weekend at The Compound. I, along with half-a-dozen beleaguered punks twice my age, came to dismantle the storied clubhouse. Our main objective wasn’t just to clean out a work/live space filled with 30 years of counterculture, but to shepherd the magazine’s crown jewel — an eight-ton archive of punk LPs and 7”s, the largest collection of punk records in the world — to its secretive, temporary safe house at an undisclosed location in the Bay Area.

When I arrived, I was met by a handful of long-time volunteers working quietly away, seemingly resigned to — or perhaps just worn down by — a fate that had threatened to befall them for decades. I had reached out a few months prior when I saw the farewell announcement online: “It is with heavy hearts that we are announcing the end of Maximum Rocknroll as a monthly print fanzine.” More specifically, I called a landline I’d found in an old issue. To my surprise, someone actually picked up. Since then, I’d been on the list of “shitworkers” (what MRR calls its volunteers) helping MRR ship its final issues and get their affairs in order.

When I arrived, we waited for a Uhaul to come back from its undisclosed location for another truckload of records — the first of four trips it would take this weekend. Longtime shitworkers Matt Badenhop and Julia Booz, along with unofficial Editor in Chief Paul Curran (MRR’s flat, democratic structure precludes hierarchical titles) had just finished delivering the 7”s to the secret drop-off point, and the LPs were next. I counted 268 50-pound boxes in all, not including the 7”s — about “six-to-eight tons of Punk,” Curran later told me. We passed the time waiting for the truck by categorizing the various defunct office supplies. “Man, the number of times I’ve been looking for some goddamn tape,” Curran would mutter when he returned, looking at the bucket of various adhesives before him. No one had any idea what to do with all of it.

In the ‘80s and ‘90s, MRR’s issues reached thousands of readers across the world and mobilized anti-establishment activists from Milwaukee to former Yugoslavia. It profiled independent punk bands like Black Flag when magazines like Rolling Stone wouldn’t even review their music (today, Black Flag’s Damaged sits in their top 500 albums of all-time). Even 42 years later, on the penultimate “new issue day,” I still saw thin bags of issues going to countries like Italy, Switzerland, and Brazil.

As we worked, MRR’s volunteer bookkeeper Mark Dober, a white-haired, bespectacled seismologist, put on a record — an EP by Wichita punk band The Embarrassment, submitted for review. From the beginning, that’s how the whole operation worked: Bands sent in a physical copy of their record/EP/demo and one of MRR’s editors reviewed it. The only rules were that it had to be punk, and it had to be independently produced. No record deal, no major label.

Unless the band explicitly stated that they wanted the record back, it was added to the archive and lined with green tape to denote its official induction to the collection. The tape was an idiosyncrasy from late MRR founder Tim Yohannan, who supposedly started using green tape in the ‘60s to separate his personal record collection from his brother Tom’s (who used blue).

One shitworker told me that at its height, MRR received upwards of 1,000 records a month. Today, the archive is a massive anthology of the obscure and underground, of self-recorded garage bands and pimple-faced teens who could barely play their instruments, right alongside self-recorded rarities from cultural touch points like Hüsker Dü and The Minutemen.

Now, its fate, like MRR’s future, sits in limbo. No one was certain how long the collection would stay at the new location; they’d considered donating it, but the thought of the records locked away in some researcher’s basement didn’t sit right with them. “We don’t want to move it to some museum, we want it to be accessible,” Curran told me.

The Uhaul finally arrived after a few hours, allowing us to start loading boxes. Curran had devised an elaborate plan to keep them organized: we loaded them in reverse-numbered order, facing backwards, snaking left-to-right from the back of the truck. George, a 60-plus-year old tech retiree who has been with MRR since 1991, barreled past me with a crate, loading with surprising speed after all the hours of heavy lifting. “Punk ruined my life,” Ambrose grumbled as she muscled a box up into the truck to fellow shitworker and record reviewer Allen McNaughton. “Ah, punk made you,” McNaughton shot back.

We finished loading by mid-afternoon and I hopped in the truck with Curran to drive out. Unfortunately, thanks to the farmer’s market happening just outside, a car was partially blocking the driveway. “Can somebody move their Tesla?!” Curran screamed out of the Uhaul window, to no one in particular. We didn’t have to search too hard for the metaphor here.

Eventually, we managed to maneuver around the stone fruit shoppers and get on the road. It was my first chance to talk to Curran alone. Curran is a wiry guy in his mid-forties with bright blue eyes and a nervous smile. He’s been a shitworker at MRR since he was a teenager and has seen the magazine through some tectonic shifts since Yohannan’s death in ‘98. On the drive, he conceded that at times MRR’s anti-establishment ethos has gotten in its own way. “That’s the problem, no one’s in charge,” he admitted. “We have 20 people on the board [a nebulous, semi-active group of longtime shitworkers formed after Yohannan's death to vote on issues concerning the future and editorial direction of the magazine]. It’s hard to get stuff done.”

It’s a wonder MRR has survived this long. Set aside the economic feat of producing and distributing a print magazine by hand via volunteers — the brutal self-policing of the punk community alone should have done it in. Punk music has been pronounced “dead” at least ten times throughout MRR’s existence and since its inception, the zine, and the genre as a whole, has arguably “sucked.”

Except it didn’t suck, obviously, and everyone there knew it. MRR reached punks in prison, on remote islands, under totalitarian regimes. The 432 novella-sized issues were themselves a masochistic testament to the “do it yourself” ethos of the genre. Month after month, its shitworkers never failed to ship an issue, even when money was tight (and it always was).

MRR continues to run its radio show every Sunday (give it a listen) and they’re slowly populating a website with reviews. But without a revenue stream, there’s still a metaphorical Tesla blocking their metaphorical driveway. I can��t say I’m not worried, but then I think about the final words of MRR’s farewell announcement: “Punk rock isn’t any one person, one band, or even one fanzine. It is an idea, an ethos, a fuck you to the status quo, a belief that a different kind of world and a different kind of sound is ours for the making…” Not even rent prices can stop that.

We pulled up to the house to unload the final crates, and for the first time I saw the archive’s new home. Much like the archive’s previous accommodations, it’s unassuming. I can’t tell you much, for the security of both the residents and their new charges, but I’ll say this: The little house has bold green trim around all the windows and doors. It looks just like tape.