At the end of August, 15-year-old Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg arrived on the shore of New York City after sailing across the sea in an emissions free-yacht to make an appearance at the U.N. Climate Summit. Across the globe 1.4 million students have protested alongside her, joining her in the Youth Climate Strikes reflecting the growing anxieties and fears stemming from new reports and research, seemingly released every few months, that paint an increasingly grim future about the planet’s health.

With the timer rapidly counting down, education about climate change remains increasingly important. According to a survey conducted by NPR, more than 80 percent of parents in the U.S. support the teaching of climate change, and 86 percent of teachers agree that climate change should be taught. But these robust supportive numbers don’t match up to the true state of education around climate change for young people and children: 45 percent of parents said they had never spoken about the topic with their children, and 55 percent of teachers said they’ve never covered climate change in their classrooms or even talked to their students about it.

Children’s literature is trying to pick up some of the slack. There’s proof that engaging in conversations across generations can be an effective first step into the movement against the climate crisis. One 2019 study found that young people can increase their parents’ level of worry about climate change, and teaching 10-to-14 year olds about the crisis oftentimes led to a direct change in the parents’ views on the subject. What better way to start that conversation than a bed-time story?

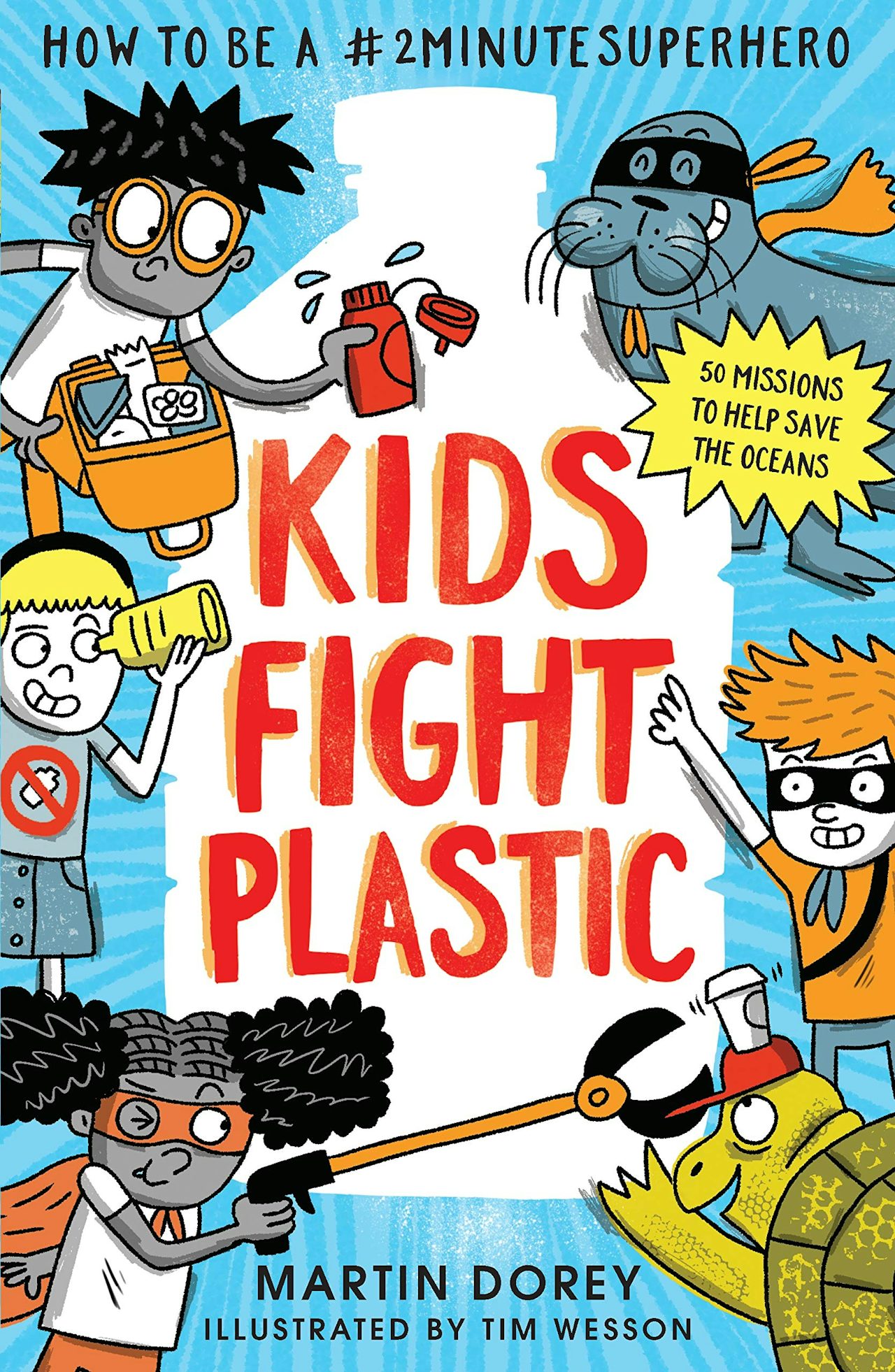

Modern authors have a challenge on their hands: find new ways to teach young children about a multifaceted, often depressing environmental issue while remaining realistic and optimistic, and attempting to offer feasible solutions suitable for children. These authors must find the best way to execute the information, rather than just screaming the facts. “How do you tell kids to tell their parents to put solar panels on their roofs?” Martin Dorey, author of Kids Fight Plastic, a children’s book about how to combat plastic use for children aged seven to 10, told The Outline. “You can't do it. So it has to be done in a way that’s almost like second hand communication.”

Kids Fight Plastic is a largely a solutions-based book, informing kids about “two-minute” solutions to the plastic problem. Dorey asks his young readers to do things like monitor their family’s plastic bag usage as well as what their parents buy at the supermarket, or something as simple as picking up trash and litter when you see it. Coming from his background as an anti-plastic activist, these sorts of practical, individual-based solutions are a natural fit for Dorey’s foray into children’s literature.

“[Plastic] is really tangible, and it’s problem based,” he said. “Climate change is just nebulous to so many people.” Now he’s working on a second book in the Kids Fight Plastic series, which will be called Kids Fight Climate Change.

Many of these practical solutions may seem overly simplistic, and a Band-Aid for a much larger problem — because they are. A recent report found that just 100 companies are responsible for 71 percent of global emissions since 1988. This month, Elizabeth Warren, in a seven-hour town-hall on climate change, spoke about rhetoric pushing for individual action distracting from real culprits like the fossil fuel industry.

However, these simple steps for young kids can protect their mental health. A 2017 study by the American Psychological Association on mental health and climate change, found that “connecting climate impacts to practical solutions encourages action while building emotional resiliency.” In children that had already experienced the detrimental impacts of climate change, through disasters like devastating hurricanes or floods, data found that a combination of reflection on the climate, coupled with hope and advice from caregivers, brought “positive transformation and healing.” In a recent speech at the World Economic Forum Greta Thornburg told the audience, “Adults keep saying, ‘We owe it to the young people to give them hope.” she said. “But, I don't want you to be hopeful. I want you to panic. I want you to feel the fear I feel every day. And then I want you to act.”

Panic itself is not the healthiest route of instilling action in children. The APA found that children who fear losing control over an unknown future due to climate change can often develop obsessive compulsive behaviors as a result. This can range from picking up every piece of garbage on the way to school to the extreme example of one young patient who had to check off a rigid nightly routine of preparing and educating himself on climate change in order to “ward off panic attacks and insomnia.”

Children’s books that explain the climate crisis, while weaving in an aspect of community and collective action, find the right balance. In 2007’s Winston of Churchill by Jean Davies Okimoto, one polar bear becomes the leader for the entire group being threatened in Churchill, Manitoba, where “global warming” is impacting their habitat. Led by Winston, who even gives one of Churchill’s impassioned speeches to rouse action, the polar bears make signs and protest. (Obviously, the book elided some of Churchill’s other beliefs.)

Themes of protest and community organizing continually crop up as solutions to the climate problems in many of these texts. “For older kids, and middle school, the leap from we can all do our part no matter how small to civic engagement is really one that I hope is there,” Okimoto told The Outline. “That’s how they’re going to get involved and get leaders who change the system.” All of these strategies are interconnected: small individual acts will hopefully lead children to be more environmentally conscious, which then increases pressure on parents to act or seek out information, which eventually gives way to a civically engaged teen holding their elected officials accountable.

“Kids played a real part in changing the culture in this country about smoking,” Okimoto said. “Kids who were in schools were taught about the dangers of smoking and what it did to your health. And of course, they'd go home and hear their parents smoking, so they would put a lot of pressure on the parents to change their behavior.” She’s hopeful a similar pattern will follow for climate change.

Perhaps the best book to execute the delicate balance between reality, optimism, and collective action is 2016’s The Tantrum that Saved the World, which started as a Kickstarter campaign and quickly garnered support from hundreds. The book follows a young girl approached by dozens of climate refugees moving into her home. Among them are polar bears, Syrian farmers, Bengal tigers and New England fishermen. As she tries to find a solution to their homelessness, she faces off with the corporate suits at City Hall who tell her no solution can be found because “fixing these problems will put us in debt.” She follows this rejection with a tantrum strong enough for the whole world to rally around, leading to protests, collective action and organizing with neighbors and animals from around the world.

The end was the trickiest part for co-author Megan Herbert, who wanted to find a middle ground between a positive ending (especially for a book that might be read to children just before bed), while remaining realistic. “[The protagonist] made some headway and some success with her activism, but she acknowledges that she's just beginning the work she has to do,” Herbert told The Outline. “That's the message that that gives kids agency, but doesn't dumb it down. It doesn't say, ‘and everyone lived happily ever after because they went to one protest.’ It says, ‘this solution will work, but you have to do the work.’”

She continued: “One of the essential things I found out early on, was that if children get small snippets of information about very big, scary topics, and they're of an age where they can't fully process what it all means, then they will fill in the gaps in their own mind, and usually imagine something a lot worse. If you've talked to any psychologist about kids dealing with those sorts of issues, they'll all agree that it's much better to inform children in language that they understand, rather than make it a taboo subject.”

Ultimately, all these approaches mean nothing if the market doesn’t enable them. I visited my local Barnes and Nobles’ children’s area, hopeful I’d at least find the Magic School Bus Climate Change edition. But I could only find three stories that addressed climate change, in the one science aisle among the rows and rows of picture and chapter books. I picked out nearly every picture book with penguins or polar bears on the cover, hopeful that they’d be about the warming Arctic, only to find pictures of penguins carrying suitcases full of winter hats and scarves instead.

“There aren’t a huge number of climate change books out there,” Herbert said. “The reasons for that are complicated, but boil down to the fact that traditional publishers generally don’t like message-heavy, issue-based books, and climate breakdown is not really an easy topic for a picture book.” She and her co-author Michael E. Mann decided to go the Kickstarter route for a number of reasons, among them the lengthy process of traditional publishing and a desire to cross genres, rather than being labeled as strictly a picture book, or strictly educational text. But the demand for books like these is only increasing. The Guardian reported last month that children’s books looking at the climate crisis, global warming and nature have more than doubled over the past 12 months, according to data from Nielsen Book Research, as have sales.

The books that I did find all had widely different approaches to the subject. Chelsea Clinton’s Don’t Let Them Disappear was lukewarm, offering only a bulleted list of actionable items for children reading at the very end. Another, World Without Fish, leaned into the dystopian, dark reality in its opening passage: “This is the story of how the Earth could be destroyed.” Of course, these are all approaches you can find in writing aimed at grown-ups, too. There is no consensus on how to write and teach climate change to children, partly because the adults in the room are still trying to figure out how to talk about it among themselves.