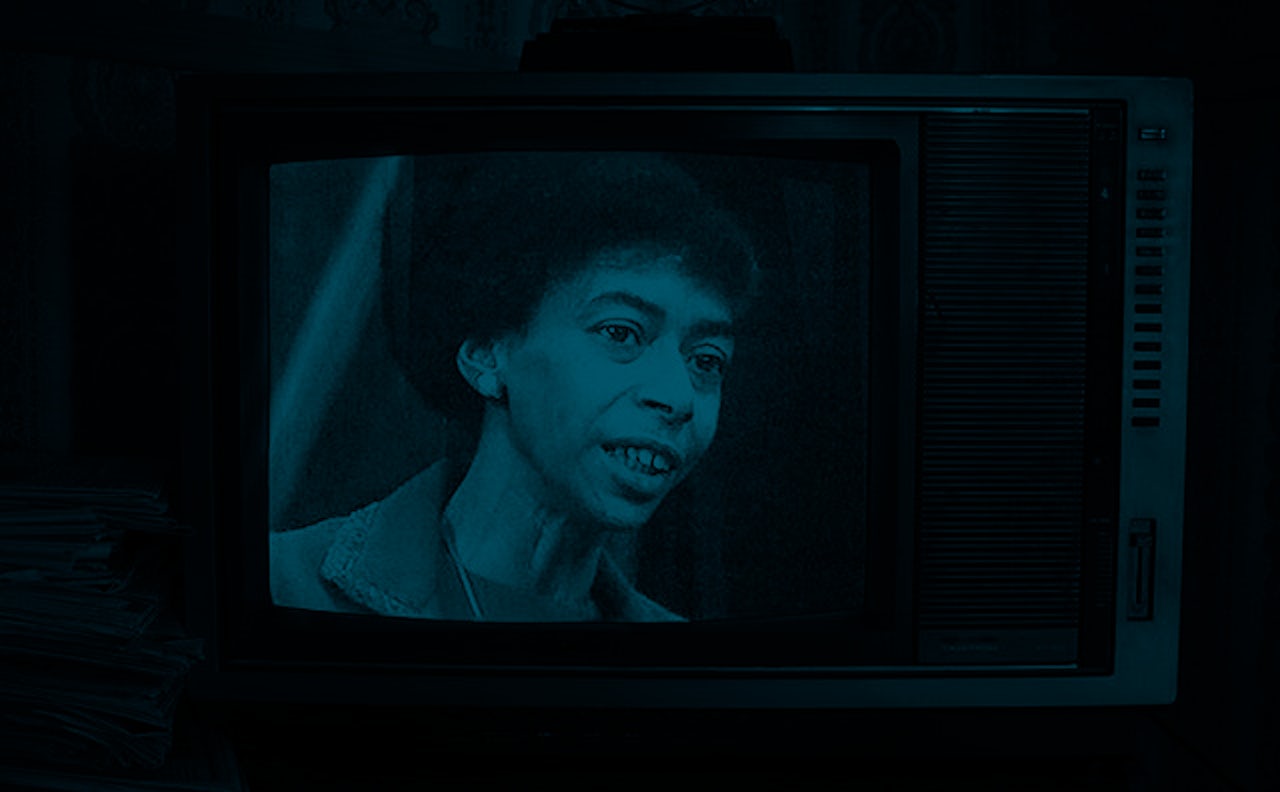

In December 2013, the Internet Archive, a non-profit in San Francisco committed to creating a free digital library, received 70,000 VHS tapes comprising a treasure trove of televised news. Apart from coverage of historical events like 9/11, the tapes contained quirky local stories that never commanded particular attention beyond the day they aired. They all came from a single source: Marion Stokes, a Philadelphia woman who began recording the news during the Iranian Hostage Crisis in 1979, and didn’t stop until her death in 2012.

Stokes is the subject of Recorder: The Marion Stokes Project, a new documentary that highlights her work as an archivist, but paints a complex picture of a woman who was brushed off as an eccentric for most of her life. For over 30 years, multiple tapes (sometimes as many as eight) would record concurrently across multiple televisions as Stokes personally watched two monitors at once. If she was attending gatherings or running errands, her outings would end abruptly when she had to go home to change out the tapes. Her obsessive work furthered her isolation from friends and relatives, as well as her son Michael Metelits, adding to the mystery as to why she undertook and continued such an ambitious project.

Stokes’s archival work is unprecedented; a time machine back to the advent of the 24-hour news cycle covering historical and cultural events that otherwise would have been overlooked. It was also a lot: Her tapes, books, computers, and other belongings lined the hallways of her home, as well as her other apartments, and her relatives’ homes. Stokes left her collection to Metelits who, after some consideration, decided to donate his mother’s tapes to the Internet Archive. Right now, the tapes are stored in two full-sized shipping containers stacked on top of each other in the Internet Archive’s physical archive and “seamlessly going on into infinity,” Roger Macdonald, the Director of the Internet Archive’s Television Archive, told The Outline. While some of the tapes have already been digitized, the Internet Archive is currently trying to raise the $2 million dollars necessary to digitize the rest of the tapes, and put them online for free, where they can be preserved, used, and repurposed by journalists, researchers, and anyone interested in television news history.

The Outline spoke with Matt Wolf, director of Recorder, about why he made his new documentary, the process behind it, and Stokes’s unparalleled archival work. Recorder premiered at the Tribeca Film Fest last week and is set to play in May at Tribeca, HotDocs in Toronto, Montclair Film Festival, and Maryland Film Festival. Further distribution is yet to be announced.

When did you first hear about Marion Stokes?

When the Internet Archive originally acquired Marion’s collection, there was a wave of initial press. The information was limited, and I tracked down Michael, her son, through someone I knew at the Internet Archive. My producer, Kyle Martin, and I went down to Philadelphia and we saw where her son was living at the Barclay. When we entered her apartment, Michael was there with Marion’s secretary Frank. There were hundreds of Macintosh computers in their original boxing, and they were organizing and liquidating Marion’s computer collection. We were like, “Wow this is not what we were expecting.” The conversation we had with Michael and Frank was very emotionally intense, and we realized that this wasn’t just a story about an unusual and unprecedented collection, it’s a pretty intense family story too.

Is the family story what drew you in?

Initially, I was just intrigued by the idea of trying to grapple with an archive that kind of has everything and anything. I liked the idea of fuzzy degrading aesthetic of VHS tapes and so I was drawn to it for those artistic and conceptual reasons, but as I learned more about Marion, I recognized how unusual and fascinating a character she is. As I was making the film I found myself gravitating more and more to her personal story and trying to figure out how the archive illuminated that and vice versa.

What was it about her personal story that most interested you?

This tension between idiosyncrasy or eccentricity, and insight and vision. I think that’s something I gravitate towards in subjects for films in general: something that can be dysfunctional and insightful at the same time. Someone can be marginalized and they can also be visionary. In the case of Marion, there was great personal sacrifice in her personal life and great personal pain caused for others by Marion in pursuit of this project. So I thought that rather than psychological explanations for Marion’s projects, I was more interested in these larger ideas about pursuing unprecedented projects privately outside of the mainstream and outside of institutions and the consequences of that.

In your documentary, you touched on how Stokes’s work was a subversion of power.

Yeah, I think what she was doing was anti-authoritarian. Obviously we know that in her political history she was a communist and was spied on, but she retained a kind of skepticism of official histories and institutional power and that’s partly what led her to pursue this ambitious project on her own terms, privately. I think some people might cast that away as hoarding or as eccentric, but in fact there was a political rationale to it, I would argue.

You don’t just focus on the positive aspects of her work, but you also pointed out her faults and negative sides to her work and her personality. Was that difficult to do?

No, it’s a problem to romanticize subjects, but it’s also a problem to demonize or psychoanalyze them when they’re not around to speak for themselves. When I make films about other deceased subjects, I think the fundamental issue is fairness; fairness to the person who can’t tell their own story but also fairness to the people whose lives were affected by their stories. I felt that it was only fair to tell a balanced story about Marion, and she’s a paradoxical and complex figure who did remarkable things and also did some destructive things as well.

You used a lot of archival footage in the documentary. Was all of that from the collection?

Yeah, almost all of it. There’s a few minor exceptions, material before the period which she was taping. But yeah, all of the other material came from Marion’s tapes.

How was it navigating those 70,000 tapes?

We had to index Marion’s entire collection in a grassroots way. Marion wrote on the spine of all of her tapes the date, the network, the time period she was recording, and sometimes other information that we called meta-data. She had packed up all of her tapes through the course of her life in cardboard filing boxes, which Michael and Frank had organized and put into storage, and then shipped to the Internet Archive. We worked with an archivist at the Internet Archive named Trevor von Stein, and we created a kind of unique conveyor belt system in which a camera was mounted above to take photos through the top of the box to capture the spine of the tapes. When you zoom in you can read what Marion wrote. We put out a call for volunteers which, to our surprise went kind of viral, and over 50 people from around the world signed up to help us log tapes. Via Dropbox and via a Google spreadsheet that was shared globally, people began to transcribe what Marion had written on these tapes into what we called an index.

One volunteer, Katrina Dixon, rose to the occasion and she became the supervising archivist and completed this index of 70,000 tapes. Then the next step was figuring out what to pull, obviously. So I relied on Wikipedia because every year from 1975-1989 has a Wikipedia page, and that’s an assortment of big ticket historical events to weirder marginal histories. So anything from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the collapse of the Miss America Pageant stage. I was interested in both so I made a wish list of dates that were of interest to me. Katrina would go through our spreadsheet and identify tapes from that day or that time period or the following day, and we would send those to our preservationist at the Bay Area Video Coalition who would digitize and preserve those tape. We only digitized 100 tapes, but Marion recorded in Extended Play [a setting that allowed for up to 6 hours of recording time, at the expense of visual quality] so we had approximately 700 hours of footage. Then I would kind of scrub through all that footage marking material of interest and what I found is that the most interesting stuff wasn’t what I was looking for, it was other kinds of detritus from the trashcan of history on TV.

Were there any historical events that you knew from the beginning you needed to include?

I knew that the Iranian Hostage Crisis is what catalyzed Marion’s project. The challenge of a film like this is not to just make a “greatest hits” timeline of history, and to repeat things that people already know. It’s difficult to go deep into any particular news events because it’s a distraction from the central narrative, but the Iranian Hostage Crisis was both central to Marion’s story and a significant historical event that changed the medium of television.

One event that sticks out in my mind that you included wasn’t necessarily historically significant, but was a story about a woman being buried inside her Cadillac.

[laughs] There were so many amazing, weird local news stories like that... especially from the ’80s. There’s so much fascinating stuff, I wish I could have used more. There was another one about this enormous snake coming out of a woman’s toilet. There were so many that we couldn’t use that were so just weird and strange.

One of the more striking parts of your documentary is the news coverage of 9/11. You juxtapose reports from CNN, ABC, CBS, and Fox News and play the real time coverage on the morning of 9/11. What made you decide to do something like that, and with that event in particular?

We wanted to use the footage in a few ways. One was to actually show historical events like the Iranian Hostage Crisis; another was to show these marginal histories in little capsules and to collage material from the tapes almost like video art. We wanted to figure out how to use this material to show the depiction of news in real time. We also wanted to treat an event that everybody is familiar with but to show it to them and to help them experience it in an unfamiliar way.

9/11 seemed appropriate because of anything that’s happened in the last several decades, that’s one thing that is a collective experience that was witnessed on television that we all share. There’s a few of those things like the Challenger explosion or the Kennedy assassination, but for these times, 9/11 is that thing. Watching it in real time, I think the reason people respond to that is because it really viscerally puts you back to the moment where you first saw those images on television. I think everybody has their own personal experience of going to a television and seeing what was happening and ever since that happened, the politics of the world have changed. It’s such a collective experience that happened through television that it’s uncanny and a bit strange to see how information spreads in real time across TV and how at a certain point we are all collectively experiencing history together through TV.

Are there more recent event that you think were experienced in the same way?

I think a recent historical event that people experienced on TV collectively or streaming online via TV was the Kavanaugh hearings. I was on set filming, but everyone I know was watching that live. There’s lots of examples of that, but that’s a recent one where it’s a devastating thing that people saw in real time, and it was a collective experience. There are many of those. Some are more permanently imbued in our minds and memories than others, but it happens. Even now that the media, the nature of it, has changed and been stratified in a different way. An aspect of the media that I think is important to recognize is the collective experience that people have.

You said during the Q&A after the premiere that you hope your documentary will help spread awareness about Stokes, her work, and the Internet Archive’s plans to archive her work. Is that the central takeaway you want people to have from your documentary?

No. I think I want people to have an emotional experience hearing about a very unfamiliar story from a very unexpected figure. For me, my films are always about grappling with big ideas that are huge in their stakes, but also having an intense yet specific emotional experience. It’s about holding two things simultaneously, having an emotional encounter with a family story that’s very unfamiliar but maybe universal to a certain extent, and then also grappling with the totality of media. I mean, it can’t get bigger than that. But, you know, through specific examples and a specific demonstration of this archive and its value in the present, like how things from the past inform how we think about the present and the future, that’s why it’s important to hold on and to save things.