In “The Drowned Giant,” a short story written by speculative fiction writer J.G. Ballard, a large giant’s corpse washes up on the shore of a small town. The narrator is taken with the monster from the beginning, visiting it when he can, but his fellow townspeople seem more interested in how they can put it to use. Men, women, and children climb on top of the monolith to get a better view, and slowly parts of the giant begin to disappear. Its limbs are removed and sold or put on display; its skin is tattooed and branded with immature slogans and hateful symbols such as swastikas. The monstrous corpse becomes the canvas with which the townspeople express themselves, before they erode its identity for their own enjoyment.

Ballard’s drowned giant is an apt metaphor for a lot of things, such as how religious belief involves a lot of projection on the worshipper’s part, and how death becomes a public display and exploitation of suffering. Today marks the 10th anniversary of Ballard’s death, which was followed by the requisite eulogies and tributes, all of which — as is now standard for the post-death content economy — tried to make immediate sense of his life. Some of this involved grappling with the apparent contradictions: As Martin Amis wrote in The Guardian, Ballard was a suburbanite and quite a cheerful fellow, a peculiarity given the themes of sex, violence, and alienation in his work. How could someone who lived in the cheery suburbs dream up such wild and, at times, disturbing stories? Well, as theorist Mark Fisher wrote in his own short tribute to Ballard, surrealism is abounds in the suburbs. Ballard was a product of his environment: high-rise apartments, brutalism, exuberant wealth, and the clash of the ’60s counterculture. In that context, it wasn’t difficult to imagine at all.

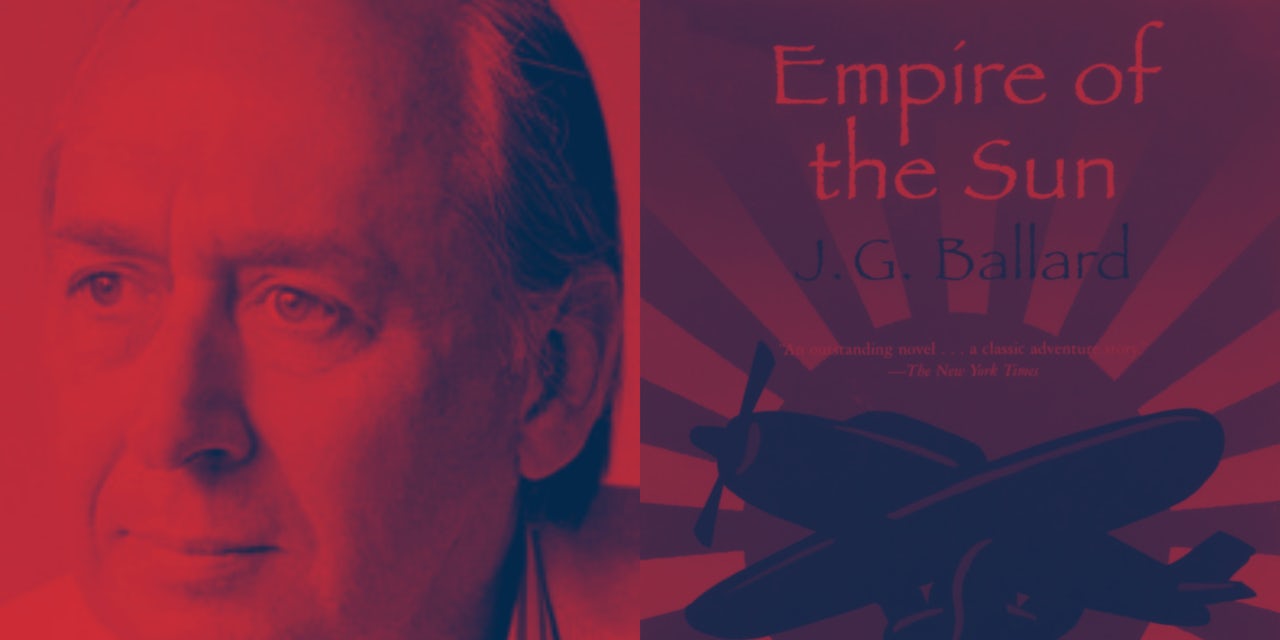

In his tribute, Fisher wrote that “assimilation is sometimes the most effective kind of assassination.” According to Fisher, Amis was a co-conspirator in this ongoing assassination by focusing on Ballard’s oddness, rather than his work. It’s in his work, not his life, that we find familiar traces of our current reality: a growing class divide (Millennium People), the isolation that results from overuse of modern technology (Super-Cannes and Crash), and our turn from outer space to what Ballard called “inner space” — a close encounter with our bodies and ourselves, opening up a space for greater recognition through confessional posts on Twitter and autobiographical writing (a theme that can be found in most of his work, but especially Empire of the Sun). The author’s work has not faded from relevance; his ideas have been taken apart and scattered throughout society.

Unfortunately, apart from the narrator, the drowned giant is forgotten. Bits and pieces of the giant human body exist in other spaces, but are not seen as what they came from; they’re instead displayed as part of a sea monster or beast with no origin. The story ends with the giant’s skeleton still washed up on the shore — overlooked during the winter but used as a perch for seagulls in the summer. Fisher ends his tribute to Ballard by asking: “Where are his 21st century inheritors, those who can use the fiction-kits Ballard assembled in the 60s as diagrams and blueprints for a new kind of fiction?” They may not realize it themselves, but Ballard’s inheritors —both fictional and factual — have already been here for quite some time.