On April 19 last year, the body of the 42-year-old Mexican rapper Mr. Yosie Locote was dumped in an empty lot in the western city of Guadalajara. A note claiming he had been killed because of a connection to an enemy of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel was pinned to his chest with a screwdriver. In a separate case three days later, authorities arrested another local hip-hop star, the 24-year-old Christian Palma, known as Qba, who confessed to dissolving the dead bodies of three film students in sulfuric acid on the orders of that same organization.

Both artists were pioneers of rap malandro (thug rap), a style of hip-hop the Mexican press has cast as the soundtrack to the country’s drug war. With performers rapping about meth abuse and massacres, the media blames the music itself for perpetuating gangland violence. But defenders of the genre argue that rap provides youngsters from poor urban areas with an attractive alternative to drug cartel recruitment.

Young people have taken to this music with enthusiasm in Guadalajara, the capital of the state of Jalisco and Mexico’s second-largest city. Although Jalisco is better known for tequila and mariachi, Guadalajara’s low-income Oblatos sector has become a mecca for the country’s hip-hop scene, spawning numerous stars including Mr. Yosie Locote and Qba.

“[Hip-hop] is blowing up right now,” said Guadalajara rapper Push El Asesino (Push the Killer). “But problems can follow you when you’re rapping about the streets and violence.”

Oblatos is home to 250,000 people and around a dozen warring gangs. The gunfights and grieving parents multiply each year. “People used to scrap with stones,” Push, who grew up just outside the neighborhood, told me. “Today, everybody has a pistol.”

At 31, Push is a veteran of Guadalajara’s rap scene. He has collaborated with most of the city’s top rappers, including Qba, who appeared on his 2016 single “El Vicio & La Calle” (“The Vice and the Street”). Push also worked with Mr. Yosie Locote on early tracks such as “Dame Un Motivo” (“Give Me a Motive”) from 2012 and “La Calle En La Piel” (“The Street in the Skin”), released two years later.

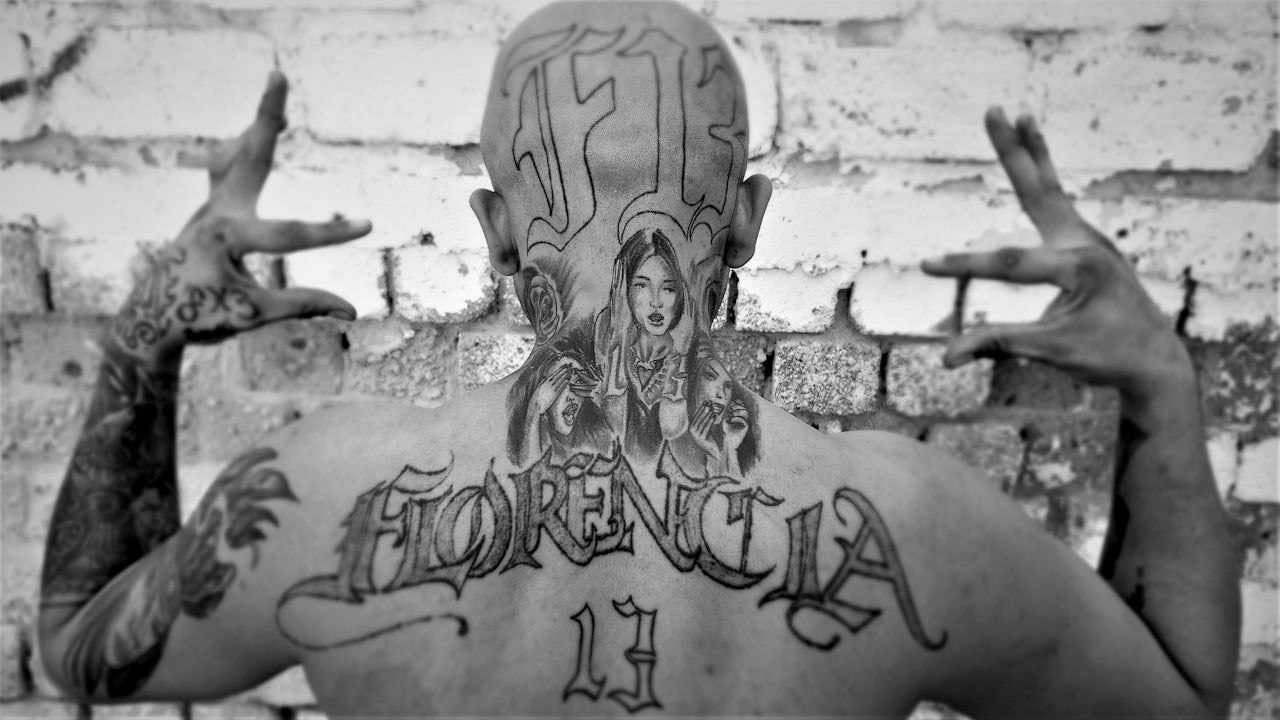

Push stressed that his relationship with both rappers was purely artistic and he had no street gang or cartel affiliations. In contrast, Mr. Yosie Locote was a known member of Florencia 13, an offshoot of the Los Angeles gang of the same name. Florencia 13 is the largest of the “first generation” cliques that emerged in the 1990s when Mexican deportees returned from the United States, bringing gang culture with them.

“These groups correspond closely to their Mexican-American counterparts,” said Miguel Vizcarra, the general coordinator of the academic study Puro Loko de Guanatos: Masculinities, Violence and Generational Change in Corner Groups in Guadalajara. “We see identical tattoos and graffiti. They also have a similar organization, with pseudo-military ranks like generals and soldiers.”

Florencia 13 aligns with the Sureños, a Southern California group linked to the Mexican Mafia, a U.S. prison gang. They flaunt the blue bandanas associated with Sureño gangs, while avoiding the red clothing of the rival Norteños from Northern California. Gang members adopt the “cholo” dress code of shaved heads and baggy tees. They wear tattoos of the number 13 — representing the thirteenth letter of the alphabet, the letter M, for Mexican Mafia.

In Oblatos, gang affiliation does not historically imply links to the cartels. Groups such as Florencia 13 are more interested in a shared identity wound up with their specific territory. They gather at night on their designated corners and defend the neighborhood from unwanted intruders (including rival gangs and the police). In fact, Vizcarra said many locals feel the gang provides protection from criminals.

Florencia 13 garnered media attention after the U.S. rap label Cirkulo Asesino signed Mr. Yosie Locote, releasing his first album Trece Reglas del Varrio (Thirteen Hood Rules) in 2012. The record offers a vivid portrait of gang life, set to dark beats influenced by West Coast G-Funk. But despite his growing profile, Mr. Yosie Locote stayed in Oblatos. He was a regular on the street corner, even as predatory newcomers eyed his territory with interest.

Gang culture in Mexico transformed after the rise of the Jalisco New Generation Cartel (Cártel de Jalisco Nueva Generación, or CJNG) in the early 2010s. This ferocious group came to dominance amid a shocking wave of violence in Jalisco. The cartel was behind massacres, deadly ambushes of security forces and a rocket launcher attack on a military helicopter in 2015. “A battle for control of the streets is raging,” Vizcarra said. “It is not just between gangs and police. Today, there is a third actor — organized crime.”

In Guadalajara, the sprawling syndicate is battling Nueva Plaza, a splinter group headed by Carlos Enrique Sánchez, alias “Cholo.” As the turf war rages, homicides have soared. Jalisco recorded 2,420 killings last year, more than five times the number for 2008.

Mr. Yosie Locote was one of the highest-profile casualties of this conflict in Guadalajara. The rapper vanished from an Oblatos market on April 17 last year. His butchered corpse surfaced two days later under a threatening message scrawled on white card. “This is going to happen to all those who keep supporting ‘Cholo,’” the note began, essentially accusing him of an alignment with the principal rival of the CJNG in the Guadalajara area. However, little concrete evidence of such an association exists, and while fans demanded justice, no one has been charged with the crime.

While the murder of Mr. Yosie Locote sparked domestic media interest, it was nothing compared to the storm of global attention that stirred the following week.

On April 22 last year, police arrested two men, including Qba, in connection to the kidnapping and murder of three film students. Authorities said the recording artist had confessed to working for the CJNG, disposing of bodies in acid for 3,000 pesos ($160) a week.

The film students — Javier Salomón, 25, Daniel Díaz and Marco Ávalos, both 20 — had been missing for more than a month. According to prosecutors, CJNG operatives seized the trio in a Guadalajara suburb, perhaps mistaking them for rivals as they filmed a school project at a house tied to Nueva Plaza. The disappearance sparked nationwide protests and statements of outrage from Oscar-winning directors Alfonso Cuarón and Guillermo del Toro.

Last December, the United Nations insisted Mexican authorities keep searching for the students and prosecutors reopened the case. Jalisco Attorney General Gerardo Octavio Solís has said that despite his confession, Qba and the other suspects could eventually be released due to irregularities in the original investigation, though few specifics have been released to the public.

Nevertheless, five people are behind bars for the crime. Qba sits in Guadalajara’s Puente Grande prison, where he could face the maximum penalty of 140 years.

The rapper was a rising star at the time of his arrest, registering up to five million YouTube views per video. But one friend, who asked to remain anonymous, said he earned little from music. The producers of his videos kept most of the proceeds from his work. With a young son to support, the rapper had spent years hustling as a tattoo artist on the side.

“His lifestyle contrasted with his YouTube numbers,” the friend said. “He wanted to do something with his life… Unfortunately, in that environment it’s difficult to keep things clear.”

As a teenager, Qba would meet his now-disbanded gang, Infernus 21, on the corner opposite his house. Since forming on the fringes of Florencia 13 territory a decade ago, Qba’s gang had fought the older, more powerful crew. The rapper even fled for his life in 2015 and lived in a drug den in the suburbs.

Over time, the influence of relatively benign Mexican-American gang culture has waned, while the nihilism of the domestic drug war has taken hold. According to Vizcarra, Infernus 21 was an archetypal “second generation” clique — loosely organized and with a more individualistic ethos. Its members also displayed a startling familiarity with violence, both inflicted and endured. Unlike older gangs, Infernus 21 affiliates claimed no allegiance to the Mexican Mafia, nor did they dress as cholos.

Hard drug use is another factor separating “second generation” gangs and rappers from their predecessors. While weed was the substance of choice for Mr. Yosie Locote, Qba’s lyrics celebrate industrial inhalants, crack, and above all, crystal meth.

In recent years, meth has flooded Mexican cities, devastating marginalized communities. According to government data, use of the drug in Jalisco nearly tripled between 2008 and 2016. The CJNG oversees all aspects of meth production, from smuggling precursor chemicals through Mexico’s seaports to cooking the final product in clandestine labs. In poor urban areas such as Oblatos, corner cliques complete the supply chain, dealing drugs to their neighbors at the behest of cartels. Gang members who refuse to cooperate (or work with rivals) face swift retribution. Many others have left their gangs completely to become full-time foot soldiers for the cartels. The meth epidemic has driven this mutation, as young addicts in search of fast cash make ready recruits for organized crime.

Unidentified gunmen killed Qba’s friend Luis “Cebo” Estrada in 2017. Other Infernus 21 affiliates died in shootouts soon after. Few survivors remained in the area. It was the same story across Guadalajara, as death squads came to claim the streets for the cartels.

“The idea of a neighborhood gang is dying out,” said rapper Nez Lemus. “No one wants to be on a corner today because there are other forces at work… I saw shootouts and friends die by my side, so I chose a more peaceful path… I chose music to talk about the things that happened to me.”

Following Qba’s downfall, several rappers reveled in the second-hand infamy and produced tracks celebrating him. The most popular of these was “Free Qba,” by AB Perez, another Oblatos rapper who was himself arrested on a double murder charge last July. By the time “Free Qba” made YouTube, both rappers were behind bars in the same prison.

But the fallout from the Qba case hit many rappers hard, with mainstream media singling out rap malandro for glorifying a drug war that has claimed more than 230,000 lives across Mexico since 2006. “The news affected everyone,” Lemus said. “People in rap thought, fuck, [music agents] are going to think we’re all involved and will stop working with us.’”

Many Guadalajara artists, such as José Maldonado, who raps as C-Kan, view their work as an alternative to the drug war, rather than a component of it. Since releasing his first mixtape in 2004, the 31-year-old has achieved unprecedented success. C-Kan’s most popular YouTube video has more than 130 million views. He has even crossed over to the U.S. hip-hop world, collaborating with artists such as Xzibit, B-Real of Cypress Hill, and Compton Menace.

I met C-Kan at a café in the upmarket neighborhood he now calls home. He spent his teenage years in Guadalajara’s Cuauhtémoc Zone, just outside of Oblatos, as a member of the Cancha 98 gang. “Growing up, we were surrounded by narcos,” C-Kan told me. “They could achieve things you could only dream of, like buying a house for your mom… If it wasn’t for rap I could have ended up doing that instead.”

C-Kan believes music can help young people resist the lure of cartel life, offering a legal path to the money and recognition many criminals are seeking. His career has forged a path for other Guadalajara rappers, such as Maniako and Tren Lokote. C-Kan’s success has also rippled out to the producers, videographers, event organizers and others who have worked in the city’s nascent rap industry. He surrounds himself with a team of people from similar backgrounds, creating a growing hope that creative endeavors can help young people leave street life behind.

“Drug trafficking is a cancer that has spread across the country,” C-Kan said. “For me, music has become an escape route... There are people that will pay you for music. YouTube will pay you for videos. [Hip-hop] meant I could take myself out, take my family out.”