As a journalist and almost constant consumer of media, I feel a hint of guilt admitting this, but: I didn’t listen to the first season of Serial, and I don’t plan to. It isn’t for lack of quality; I just don’t really like podcasts. When I’ve found myself tuning in, I eventually get distracted enough to research the story with visual aides, and forget the podcast entirely. I’ll listen to them when a friend is involved, making me feel obligated, or when they include interviews with my favorite musicians. But overall, when I’m in the mood to listen to something, I’ll pick music over someone yapping in my ear any day.

So when I saw the ads for The Case Against Adnan Syed, HBO’s new documentary that picks up where Serial left off, I was intrigued. Of course, my interest was partly based on hype from friends and colleagues, because it wasn’t a documentary about another white male serial killer we all know is guilty, and because of the underlying concept of investigative journalism’s potential to influence legal cases, but nothing caught my attention more than the simple addition of a visual element.

If you also didn’t listen to the first season of Serial, the story is about the 1999 murder of high school student Hae Min Lee. Lee was missing for almost a month when her body was finally found by a passerby in Baltimore’s Leakin Park. Almost three weeks later, her ex-boyfriend, Adnan Syed, was arrested and, after an initial mistrial, was convicted of first-degree murder and life in prison in February 2000. In 2016, following the Serial podcast about the murder, Syed’s conviction was vacated and a new trial was ordered.

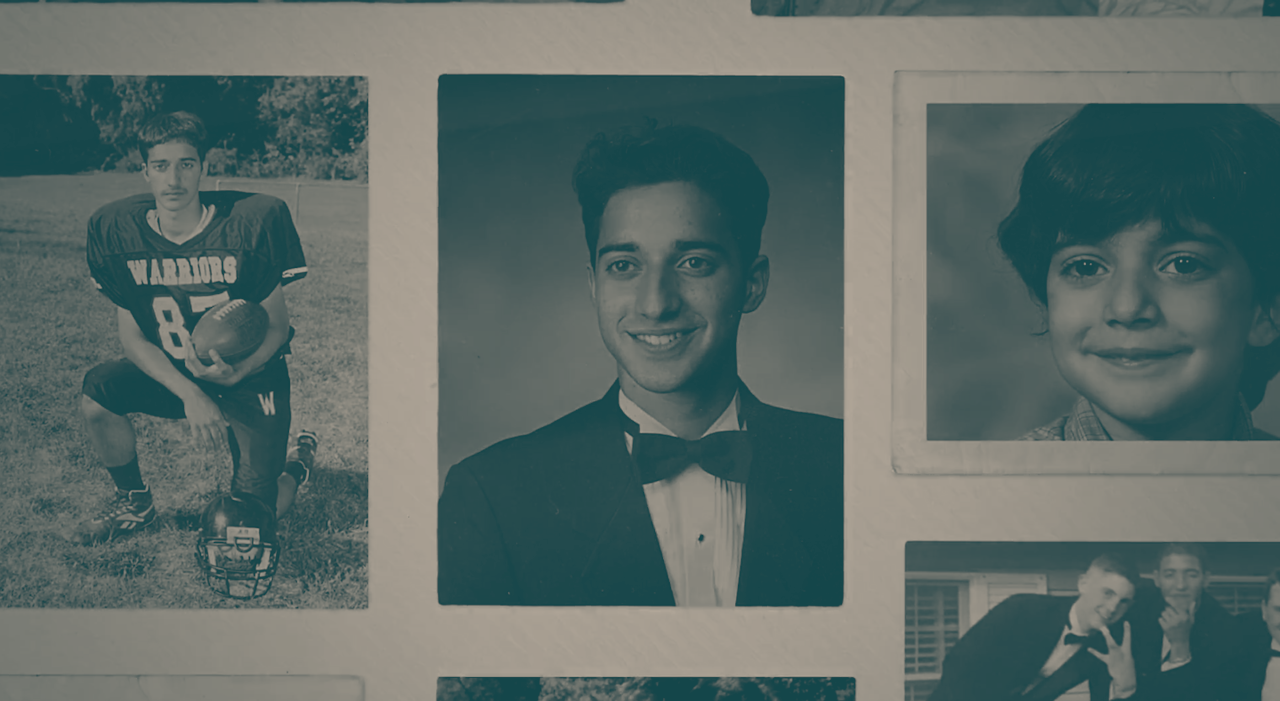

The new HBO documentary begins after the murders have already happened, and rewinds to build a timeline of Lee's disappearance, juxtaposed with explorations of Syed's supposed guilt from the present day. The young faces of Lee and Syed — in yearbook photos, during their junior prom night, and with friends — are used throughout the first part of the documentary to give an intimate glimpse into their lives. Friends, family, classmates, and teachers who serve as necessary pieces to an ever-expanding puzzle also appear in the documentary through archival pictures as well as video interviews. We witness the gruff attitude of Alonzo Sellers, the man who discovered Lee’s body, in court; the emotional facial expressions of Lee’s loved ones when they speak about her; the clear attempt, by Syed’s mother, to hold back tears when speaking about the case in the present day.

One example of the benefit of adding a visual component is how the 18th birthday party of Krista Meyers, one of Lee’s closest friends, is depicted. The documentary includes photographs of Lee’s friends and classmates at the party; they’re shown dancing, smiling, and Meyers is blowing out her candles. There was a large snow storm during Lee’s two-day absence before the party, which led to numerous car accidents and power outages. Up until the party, many brushed off Lee’s unknown whereabouts, assuming instead that she was with her new boyfriend. The birthday party marked a turning point, as Lee’s closest friends knew she wouldn’t have missed it. Lee’s absence is marked by the photos from that night, and the visible juxtaposition between her friends’ joy and their haunting voiceover realization that something is direly wrong is unsettling. It increases tension in a way a podcast never could.

The documentary’s use of animation is also spectacular, particularly when bringing Lee’s diary (what she calls her “memoire”) to life. The colorfully animated depictions of her entries give the audience a chance to see what she wrote about Syed, often loving musings about their interactions. One of the most striking scenes is when animated versions of Syed and Lee stand face to face. Syed’s brother talks about his infatuation with Lee as the animated Syed shrinks, and animated Lee grows in size. She picks him up, opens a heart-shaped door to the inside of her chest, and places him inside. The dreamy sequences makes their heartfelt connection even more believable, upping the tragedy of what ended up happening.

Given the breadth of stories available to tell, that The Case Against Adnan Syed exists at all may confuse some viewers. The first season of Serial ended in 2014, and the HBO documentary has been in the works since October of 2015. As director Amy Berg told Esquire, “we picked up where Serial left off. They did such a great job at creating the interest and picking the case apart, and I felt like we had an opportunity to go even farther into what happened after Serial.” That may be, though the reality is that Syed’s conviction won’t change: On Friday, he was denied a new trial. (And although the show has a few more episodes to go, the gist of its attitude towards Syed’s guilt is in the title.) Regardless of the real-life outcome, I’ll be following along. It’s not a podcast, after all.