Ten years ago, the Nintendo DSi was released into the world. It first hit the market in Japan on November 1, 2008, three days before Barack Obama was elected as president, four months after the release of the iPhone 3G, and seven months before my eighth-grade graduation. For my personal momentous occasion, my parents gifted me my very own DSi, an upgrade from the Gameboy Advance SP I had been using to burn the eyes out of my skull.

Whereas the Gameboy Advance SP was the natural progression of the Gameboy Advance — it had better games and a bigger, backlit screen so you could see without having to position yourself in that rare sweet spot between shade and direct light — the DSi was something new and bewildering. It boasted not one, but two screens, one of which responded to touch. Before the ubiquity of smartphones, this was a big deal. But the main selling point for the DSi was its two 640 x 580 pixel cameras — one on the back and one for selfies.

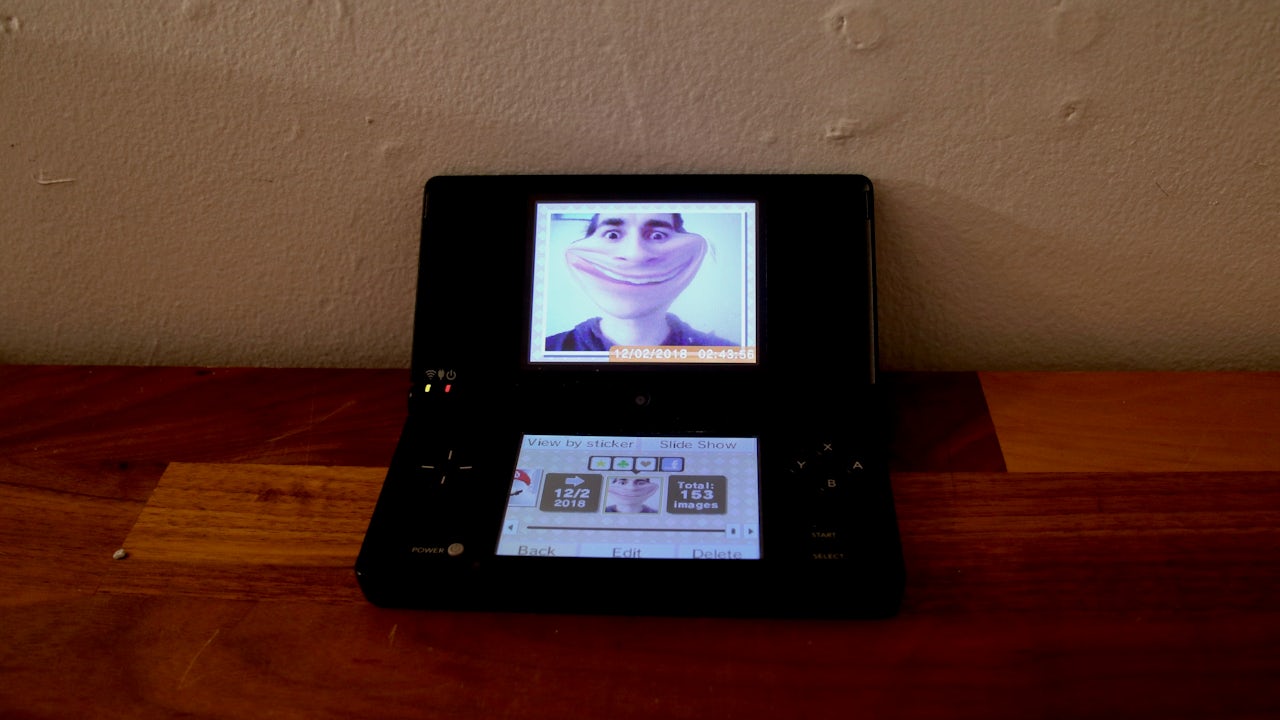

I took one picture with my DSi the day I got it, and 150 more throughout my time in high school. Then I lost my charging cable and eventually moved away for college and left the device at home, where it lay dormant for the next five years. It wasn’t until this past May that I — after a torrid affair with a GameBoy Advance emulator — decided to revive the DSi and rediscover the joys of handheld gaming, only to stumble on these photos instead.

I took my first picture in the dining room of my childhood home. Based on the woeful composition of the photo — the camera held below my neckline and angled up — I feel comfortable saying this was my first selfie. My large face, encumbered by the baby fat which I only recently lost, dominates the frame. Unlike my Myspace profile pic, I didn’t have my hair carefully pulled down as far as it will go over one eye (My Chemical Romance-style), or my mouth slightly open and eyes slightly narrowed to convey how deep I was. The straight-faced photo was a new look for me, my own small rebellion against the lifelong dictum of “smile for the camera.” I was not an angsty teen.

In a photo from the next day, I am enjoying a meal at what I thought to be the apex of decadence: Souplantation. You can tell it’s a fancy occasion — my eighth-grade graduation — because I’m wearing a collared shirt, and you can tell I was a huge nerd because I brought my Nintendo DSi with me. My face is even wider in this one, because I used a distortion effect that makes me look like a Flooglie from the original Spy Kids.

In a photo from a couple years later, I am a sophomore in high school and, apparently, still a huge nerd. On a school trip to San Diego to visit a couple colleges, I took eight pictures of me and my friend Eric seated next to each other on the bus, a few looking off into the distance, one with our mouths open as big as they could be, a couple filtered to give us the appearance of Olmec stone heads. It was a fun day, sequestered on a bus with 40 other 10th graders and a few tired teachers.

Most of my saved photos are lo-fi selfies taken by me or my friends, twisted and adorned with poorly made filters and clip art. These photos didn’t go into the cloud or on social media; they got stored on the device’s 256 MB hard drive. Looking at the photos, it’s clear that they weren’t taken with an eye towards consumption. They haven’t been curated to reflect the current status of my relationships with the people in them, the way many people’s Facebook profiles or Instagram feeds are now. I didn’t purge the camera roll of my high-school girlfriend, or the former best friend-turned-nemesis. I was wholly unprepared for the pictures of my old, dead dog, Koko, whom I don’t have any pictures of elsewhere. Nobody can dredge up my old photos by liking them, and I don’t get reminders every year telling me that I once took a picture.

It’s increasingly rare to find a trove of photos that is bound to a physical space. I could download my DSi photos onto an SD card if I wanted, but outside of the device, they are just some relatively poor-quality photos. With its technological affordances and limits, my DSi is an artifact of its time; with the photos of I’ve taken, it’s a piece of my history as well.

I don’t expect that future anthropologists will go to my DSi to learn about late-aughts culture, but I think that in 10 or 20 years, I will be able to power it up and study the person I was. Is it pretentious to say that the pictures on my DSi seem more honest compared to the ones on say, my old Myspace account? It feels like it, but I’d be lying if I said this wasn’t the best primary source document of my life at a specific time. I’m not saying that we are most truly ourselves when we don’t expect other people to look — that’s some Etsy-embroidered throw-pillow psychobabble — but that the apparent lack of intention behind the DSi pictures reveals something that my social media doesn’t: the clumsy work of building an identity, rather than presenting one. It's cinéma vérité versus reality television.

When I got my DSi, I was delighted by small acts of creation. I enjoyed recording myself on the DSi sound app, and having my exhortations regurgitated back at me in a low baritone, which seemed like a life goal fulfilled in the throes of late-onset puberty. I loved pictures that made my face look weird. I liked color filters on that, with the proper attire, could make me look like I was from the Old West or industrial England.

I don’t really like taking pictures anymore. I typically don’t care to capture my experiences to share with others, and it’s been a long time since I made my face look weird just for fun, because it always seems trivial and meaningless. But with hindsight, self-documentation and small expressions of creativity actually seem quite meaningful, even if at the time they don’t appear to be worth much.

Even with this newfound appreciation for capturing little moments, I probably won’t become an avid diarist or photographer. But I know that small doesn’t necessarily mean trivial, and in 10 more years, I’ll probably want to look at a picture of me, at this time, with my face twisted into a big, dumb, goofy grin.