Why would anyone in the 21st century choose to be a philosopher, or to read philosophy? Putting aside the fact that philosophy is an academic discipline that essentially originated with a guy writing fanfiction about his teacher, many of the big philosophical questions feel farther and farther from the experience of the world. And the ones that do feel relevant are largely assimilated into either broader cultural conversations or other, newer academic disciplines and ways of thinking that have taken up the tools of philosophy to comment on the world, often grouped under the banner of “critical theory.”

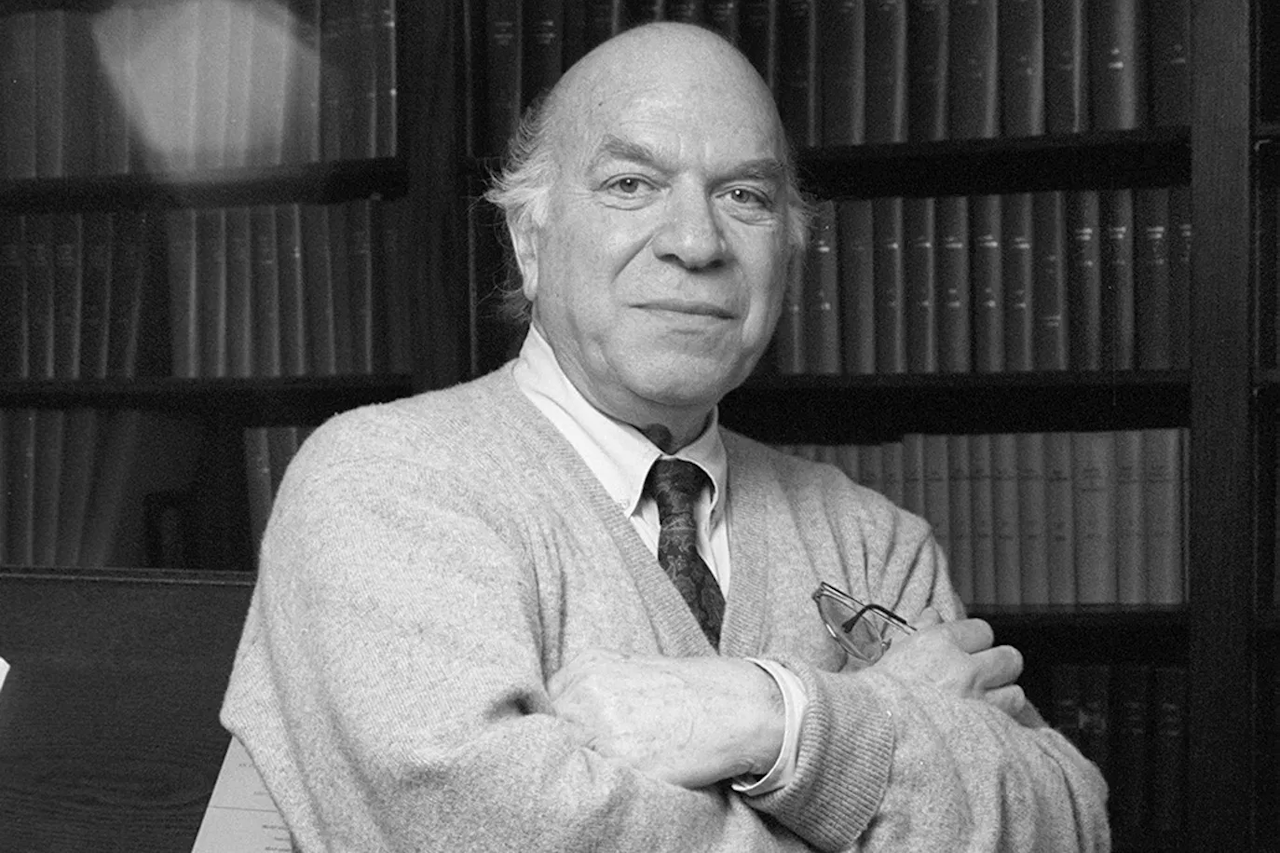

Still, I continue to read philosophy — in large part because of Stanley Cavell, the philosopher who died in June at the age of 91. Born to a pianist and long convinced that he was meant to be a musician, Cavell spent several formative years watching a lot of movies before discovering philosophy and joining the academy. Where even the career philosopher might see their work as residing firmly in the clouds, even at its broadest and most relevant, Cavell resolutely thought out of his own experience of day-to-day life. One passage in his 1979 work The Claim of Reasons proceeded from the experience of trying to teach his young daughter the meanings of different words. Having learned what a “kitty” was after seeing a cat, the girl clutched a patch of soft fur and nuzzles it while murmuring the word “kitty.” In what way was she wrong? Cavell asked.

Much of his writing was about the experience of watching movies, especially the landmark 1977 book Pursuits of Happiness, which attempted to engage in philosophical readings of a series of classic films he termed “comedies of remarriage.” An essay published in the 1984 volume Themes Out of School took focused on the experience of watching an experimental short film by Serbian avant-garde filmmaker Dušan Makavejev composed of several minutes of non-verbal sequences from Ingmar Bergman movies, literally cut out of the film reels and edited together into what was, essentially, an early version of a supercut. Makavejev, who presented the short film in person at a conference on Bergman at Harvard, created it in part as a way to understand what Bergman’s films did, and to give the assembled scholars in attendance the opportunity to ask what they got out of his (Bergman’s) work.

Cavell was not and is not unique among philosophers in his focus on the small and quotidian. Building on the writing of J.L. Austin and Ludwig Wittgenstein, Cavell’s work took up the tradition of “ordinary language philosophy,” which, broadly speaking, aims to defuse philosophical problems by recentering conversations about the meanings of words on the way those words are used in everyday human conversation. For many, this turn away from seeking objective, unalterable truths was a reason to give up on philosophy altogether, or to transform philosophical work into something that resembled therapy more than it did extended argument. (In Philosophical Investigations, Wittgenstein characterizes the purpose of philosophy as “show[ing] the fly the way out of the fly bottle.”) For Cavell, philosophy became something else, or at least something more — a way to push back against the stubborn and seductive pull of rarefied nonsense, what Cavell calls “the world’s receding from our words.”

Throughout his career, Cavell committed wholeheartedly to even the most seemingly trivial parts of the world. In Cavell’s eyes Buster Keaton was not just a silent film star; he was a symbol of and inroads to discussing human limitation and self-knowledge. The Star Wars franchise was not just a fun space opera; it was a way to think about the potential of serial storytelling, and what it meant of a work of art ceased to be able to “end” in a conventional sense. Taking pop culture and the minutiae of daily life too seriously has its own pitfalls, something that is obvious to anyone who’s tried to avoid a conversation about how capital-I Important Marvel movies are. But taking a silly thing seriously does not mean demanding that everyone view casting decisions as a matter of life and death.

Philosophy isn’t thinking about things ordinary people never think about; it’s thinking about precisely the kinds of things that ordinary people think about all the time, without distraction.

The romantic comedies covered in Pursuits of Happiness meant something to Cavell, not because they contained ideas that needed to be extracted like ore from a mineshaft, but because they struck him in a certain way. I haven’t seen most of the movies he took as his subject matter for that book, but I’ve watched enough romantic comedies and convinced myself I’ve been in love enough times to understand what he saw in them. Rather than getting bogged down with debates about “objective” quality or, even worse, canon, Cavell used film, television, and music as ways in to asking questions about the nature of existence, the use of words, and the character of knowledge. In Cavell’s hands, the silliest image became a way to, in all earnestness, examine the experience of being alive and human, of being in the world. What more could you ask for from an academic discipline that largely consists of just thinking?

Unfortunately, one of the professional consequences of taking everything that seriously is that you start to sound like a huge dork. If you’ve spent enough time consuming online writing, you’ll recognize the broad strokes of that phenomenon — painful, unhelpful earnestness — in some of the dumbest, worst stuff you can possibly read. Although his prose was far more readable than that of the average academic, Cavell’s writing was decidedly over the top and overwrought in many ways, largely because everything for him read as simultaneously a matter of the utmost importance and something that could be endlessly debated, the subject of the same elliptical, vaguely mystic style.

While some of his turns of phrase sounded like music to the right ears, it’s hard to deny that describing the act of sitting at your desk and writing as “taking thought” sounds a little full of hot air. The New York Times’ obituary for Cavell quoted philosopher Jonathan Lear’s review of The Claim of Reason, in which Lear described Cavell’s writing as “overwritten and self-conscious.” (A charge that Cavell did not quite deny.) I would argue, however, that this — Cavell’s unwillingness to every throw his hands up and say something was just a movie or just a philosophy of language argument — was the whole point of his approach, and part of the reason I love his work.

Cavell knew and convinced me of something that, in the years I had been thinking about philosophy, often elided my understanding: There isn’t any tension between philosophy and living in the world, or at least there shouldn’t be. Taking the world seriously means, in a sense, taking every part of the world seriously, and being willing (or at least capable) of expressing why you might refuse in any given instance. Philosophy isn’t thinking about things ordinary people never think about; it’s thinking about precisely the kinds of things that ordinary people think about all the time, without distraction.

As I read more and more of Cavell’s work, I discovered the way these smaller moments and observations were invariably expressive of a larger set of ideas and concerns that added up to create a delightful, nourishing, often funny body of work. In the preface to the updated edition of The World Viewed, Cavell’s book about the medium of film, he admitted to incorrectly remembering several scenes from the movies he examined — but refused to make changes to the manuscript, instead declaring that he was more interested in why he had remembered the movies in certain ways, and what that said about how people remembered films differently from other forms of art. Such an argument would be flippant today, but it totally changed the way I thought about criticism (and about thinking). Going out on a limb and being willing to be productively wrong, it turned out, was far more interesting than waiting to be right.

Still, while I loved Cavell’s willingness to plumb the depths of error and otherwise ignored phenomena, I also learned to read him for his advice on when not to think or speak. In the essay on Makavejev, Cavell recounts the experience of the entire audience sitting in silence for at least three minutes after the completion of the Bergman supercut, waiting in vain for the filmmaker to begin speaking and explain what he meant. In this experience, Cavell found a lesson that will be readily apparent to anyone who, like me, spends far too much time in compressed and agitated online spaces: “namely to recognize by oneself that one may have nothing to say in a given moment and that this need be no disgrace; a chance to see that it is no point of honor to make oneself a talking head, or machine, or monkey merely because someone (perhaps oneself) cannot bear silence and gives you a penny of attention.” Sometimes the lesson sticks; sometimes it doesn’t. (Please, share the link and tweet about this essay.)

It’s been a few months since Cavell died, and I’m still having a hard time processing it. I never met him, and never had any real interest in doing so — by the time I started reading his work, I knew enough to know not to meet my heroes. But revisiting his work in the past few weeks has reminded me of the quality I found in his writing that’s intentionally difficult to pin down, a certain springiness and flexibility that rewards a constantly renewed sense of curiosity and willingness to at least try to encounter bizarre, superficial things with a perhaps too-open mind. I’m not a professional philosopher, and I don’t know if I’ve responded as strongly, or communicated as effectively, about any piece of pop culture the way Cavell does. But I can confidently say I’ve let taking goofy things way too seriously define a lot of my life. Even in the dumbest possible spaces with the dumbest possible subjects, there’s still something to be gained from the simple act of thinking.