The start of the exhausting decade of superhero movies currently culminating in Avengers: Infinity War, Marvel’s overstuffed action bonanza that still has another movie to go, is officially attributed to Iron Man, which premiered in April of 2008. Iron Man did create the template for Marvel movies, and, increasingly, for most studio blockbuster movies. But only two months later, a more violent, slightly less successful movie premiered, one that far more accurately captured what superhero stories were about then, and what they’re covering up now: Wanted.

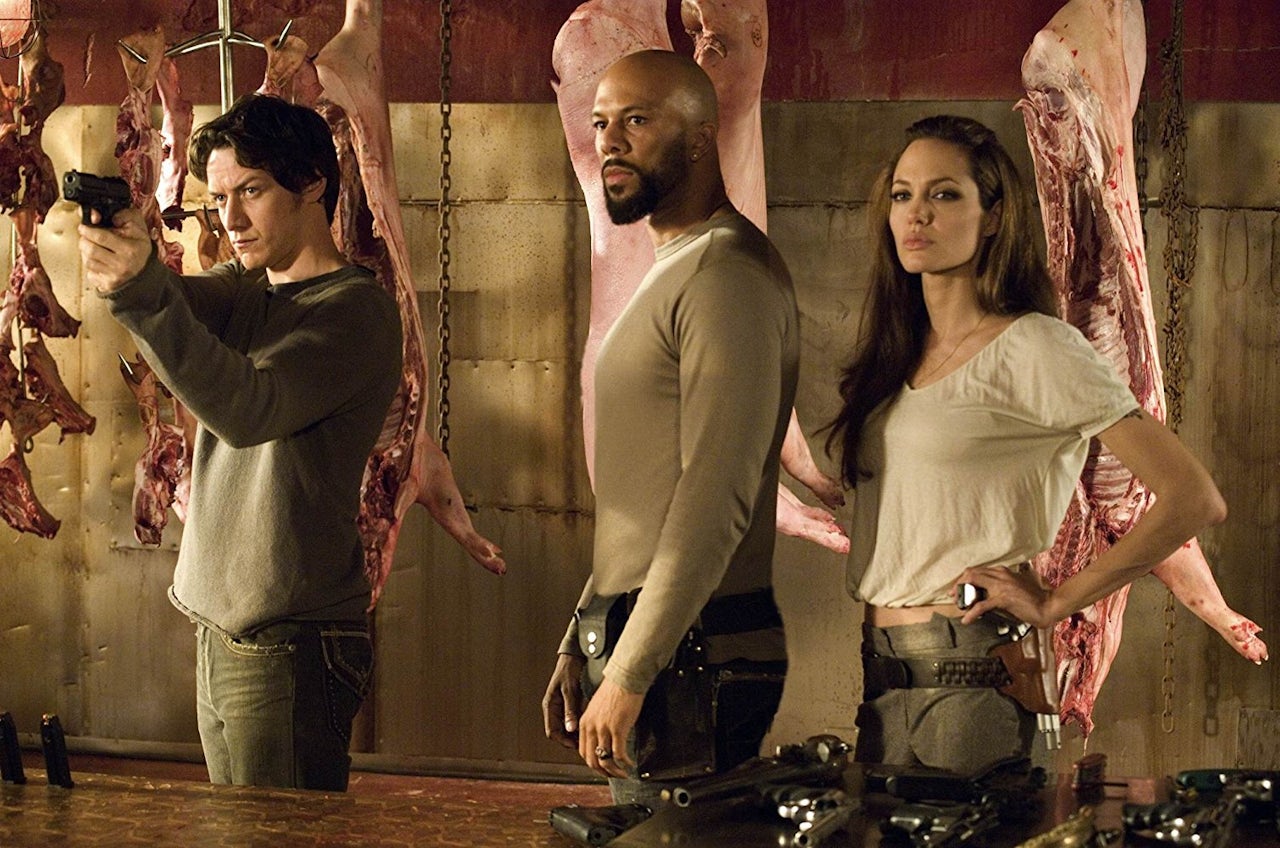

Loosely based on the comic by Mark Millar — a Scottish writer of intentionally vague political leanings responsible for some of the most popular, violent, and provocative comics released in the 21st century — Wanted follows Wesley Gibson, played with pale venom by a soft, boyish, constantly wailing James McAvoy. Wesley is a loser who works a dead-end accounting job, lives with a demanding girlfriend, and has only one friend, an obnoxious, swaggering bro who is also sleeping with said girlfriend. After learning that his absent father was actually one of the world’s greatest assassins, Wesley is recruited into The Fraternity, an organization of assassins, ostensibly in order to stop his father’s killer — though, inevitably, he ends up turning on The Fraternity and striking out on his own. There are also a lot of guns.

On its face, Wanted has all of the hallmarks of the modern superhero movie: a belabored origin story with a pseudo-scientific explanation for the hero’s powers (Wesley produces extraordinary quantities of adrenaline in his brain, which lets him experience the world in slow motion), daddy issues (Wesley spends most of the film trying to live up to the “destiny” bestowed upon him by his absent father), visual effects that almost literally beat you over the head with how cool they are (bullets popping out of people’s skulls in shots that look uncannily like Michael Jordan’s arm stretching in Space Jam), even Chris Pratt awkwardly trying to be hot (he plays the “friend,” Barry). Still, if anyone remembers Wanted now, it’s largely because of the absurdity of one of its gimmicks: that the characters can somehow curve bullets out of their guns.

The curved bullets are ridiculous, of course, but they’re also fun, allowing for some enjoyably insane shootouts throughout the movie. They feel a bit like forerunners of the glee and silliness that’s become a part of many of the better action movies of the past few years — John Wick, Edge of Tomorrow, late-period Fast and Furious. The entire Marvel Cinematic Universe runs on a seemingly endless supply of this kind of quasi-violent goofiness, which is largely drawn from Millar’s work: He consulted on Iron Man, much of the DNA of The Avengers was taken from his The Ultimates series (which presented a reimagined, more “realistic” version of the classic Marvel superheroes as government agents, an aesthetic and thematic decision translated to the big screen), and he wrote the original Civil War comic that formed the basis for the third Captain America movie. But Wanted is a much better distillation of Millar’s ethos than those other movies, and says a lot more about where the real soul of modern superhero movies lies.

Wesley Gibson is the self-mythologized hero of huge swathes of modern superhero fandom: a snarling, powerless nerd who finally gets revenge.

Wanted is an overt male empowerment fantasy, a Reddit wet dream about a guy deciding he can murder everyone who has ever been mean to him. It’s almost comical how much the opening scenes play up a sense of emasculation, even taking a page from Fight Club by having Wesley reference his IKEA table as a symbol of his fragility, because god forbid any real men should want relatively affordable furniture. The movie tells us Wesley is weak because he he apologizes too much and takes anti-anxiety medication, evidently signs of deep, human flaws. As Morgan Freeman’s Sloan, the leader of The Fraternity, puts it, Wesley needs to let out his inner “caged lion.”

By the end of the movie, Wesley has surely done so: He performs cool car stunts, kills several people, rides the top of a train through a tunnel, and makes out with Angelina Jolie in front of his now ex-girlfriend. In the final scene, he prepares to shoot Sloan, revealed to be the “real” villain of the film, with a sniper rifle while holed up in a dingy room. (Courage in this movie is being really good at using a sniper rifle to kill your enemies from a safe distance.) Just before pulling the trigger, Wesley sneers his destiny, boasts about feeling fully entitled to do what he wants when he wants, and asks the viewer, “What the fuck have you done lately?” The person Wesley is talking to isn’t meant to take this question as the motivation he needs to start organizing in his community, take up ceramics, or thoughtfully tell his friends and family how much he appreciates them. Wesley only means to inspire him to unleash the full power of his id, no matter how disgusting or cruel.

Wesley Gibson is the self-mythologized hero of huge swathes of modern superhero fandom: a snarling, powerless nerd who finally gets revenge. But Wanted wants us to feel slightly uncomfortable about enjoying Wesley’s come-up — or, at least, it wants us to think it wants that it does, because the movie presents as satire. There are all sorts of “jokes” in the movie, from the cheeky “Don’t Miss!” sign in the pharmacy where Wesley experiences his first big shootout to the way his final bullet pierces the beer being held by Barry on its way to Sloan’s head. Certainly, Wanted does have a sense of humor, sort of. (Wanted director Timur Bekmambetov’s English-language follow-up was Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter.) But unlike the MCU’s anodyne sense of camaraderie, Wanted wants you know that the real joke is always at someone else’s expense.

The most villainous character in Wanted isn’t Sloan, or any of the other killers who try to murder Wesley. It’s Janice, his boss at the accounting firm. Janice, an overweight, middle-aged woman who ostensibly rules the office with an iron fist, is “ironically” described as “anorexic” in between slow shots of her eating cake that are paired with exaggerated sound design intended to disgust the viewer. (She is conspicuously African-American in the comics, but that was apparently a dig too far for the producers.) Her primary crimes are clicking her stapler near Wesley’s ear as a way of waking him up (it’s not her fault that he’s very bad at his job), enforcing faux-friendliness at the office, and saying things like “Jesus H. Fucking Popsicle.” Basically, Janice is Pam from Archer, if Archer creator Adam Reed didn’t understand that Pam is the coolest person in the world. As far as the average viewer might relate in his own life, Wesley’s character arc reaches its logical conclusion less than an hour into the movie when he screams at Janice and tells her: “If you weren’t such a bitch, we’d feel sorry for you.”

The Marvel Cinematic Universe has absorbed a lot of Millar’s sensibility via Wanted, but perhaps his most important contribution to the MCU is the desire to have it both ways. The MCU has largely anesthetized the violence endemic to the genre, and its biggest villains tend to be CGI blobs that can serve as a focal point for explosions and lasers and intergalactic punches with no real stakes — until it’s time to get serious. (In this case, The Fraternity exists to execute the mysterious will of “fate” as communicated through binary code via a gigantic loom, for some reason, which gives them the unquestioned authority to kill people.) This is important storytelling, except for when it’s just a joke, a tonal shift they can insist upon at any point. Can’t you take a joke?

Unfortunately, no: About a year ago, Netflix bought Millarworld, the imprint that originally produced Wanted and much of Millar’s other work, and it’s easy enough to imagine the broad sensibility of Wanted becoming just another algorithmic sweet spot for the streaming company. It’s already, essentially, that same sweet spot for lots of superhero movies. The current situation, where the corporations behind superhero movies can effectively press their fans into Wesley-like service as amateur publicists-slash-bullies while claiming plausible deniability, is the best and worst of both worlds, depending on who you ask.

The products of the Millarworld deal will almost certainly be cool in the way that a curving bullet is cool. Maybe they will be more like the comics version of Wanted, where Wesley repeatedly commits rape, a crime that Millar has notably argued is identical to decapitation. It may seem stupid and crass, but the last decade has shown that the audience’s appetite for these cartoonish depictions of morality and violence has not yet diminished.

After Wesley’s big speech telling off Janice, Barry tries to congratulate him on being “the man. Wesley being “the man” is a refrain that is played as a joke throughout the movie, but it really, really isn’t, and finally, Wesley responds by hitting Barry in the face with his ergonomic keyboard. The keys, and one of Chris Pratt’s teeth, spell out the underlying message of the film: “Fuck you.”