The Austrian-American child psychologist Bruno Bettelheim was among the first to suggest that fairytales had psychological use — that stories of violent stepmothers and animal transformations helped children work through the real existential problems they were largely too young to put into words. Ironically, after his death, Bettelheim underwent something of an animal transformation himself: It was revealed that some of his practices had been fairly cruel, his credentials were forged, and much of his work was plagiarized (including The Uses of Enchantment, his most famous work, in which he gave Freudian interpretations of children’s stories).

The moral of this little fable is something like: Don’t trust a wolf just because he wears your grandmother’s clothing. But Bettelheim — or, more appropriately, Julius Heuscher, from whom Bettelheim allegedly borrowed most heavily — was onto something. Fairytales and fables have always been a way of working out or working through, of presenting what is complex and thorny in neat, allegorical packages that anyone can understand.

I first encountered what has since been described as “fabulism” in the work of Aimee Bender. Here’s an example of the genre, taken from Bender’s The Girl in the Flammable Skirt: A week after the death of his father, a man wakes up to discover that he has a clean hole through his torso. Shortly after, his wife learns that she’s pregnant. When the baby comes, however, it’s the woman’s mother, who died the year before. The story, called “Marzipan,” ends with the whole family eating frozen marzipan cake, saved from the grandmother’s funeral.

Listen to additional thoughts on queer fabulism and more book recommendations from Kit Haggard on The Outline World Dispatch.

That’s the whole of it — on the surface, a very odd and even confusing story. But underneath it’s about a couple coping with the death of their respective parents in extremely different ways: the wife, who tenderly saved even the cake from her mother’s funeral, was unable to let go; the husband was cored like an apple by his loss. This is the hallmark of fabulist stories. They make physical what is otherwise ephemeral or ineffable in an attempt, as Bettelheim would say, of understanding those things that we struggle the most to talk about: loss, love, transition.

Though often conflated, this is something distinct from the magical realism tradition of Latin America. Gabriel García Márquez — who’s become the most visible example of magical realism, and who also railed hardest against the designation — brought elements of myth and fable into the real world. But because the genre was developed in Latin America during a time of political upheaval, the work always used myth to critique, whether it was a corrupt regime or what Salman Rushdie called the garish “North,” a place that considered itself the technological and cultural center of the world, where the drive for advancement was used to pave over what was “really going on.”

Authors such as García Márquez, Luis Borges, Isabel Allende, Octavio Paz, and Carlos Fuentes, to name just a few, for the most part avoided the one-to-one allegorical relationship present in stories such as Bender’s “Marzipan,” where the father has a hole in his stomach and the mother is pregnant with her mother because they are dealing with grief. Instead, in One Hundred Years of Solitude, García Márquez has Remedios the Beauty ascend into heaven, or surrounds Mauricio Babilonia with clouds of butterflies because that’s just how things sometimes are, and the northern so-called cultural centers have simply drawn the line between what is real and what is magical too firmly.

The last ten years have seen a new bloom of fabulist writing. Bender, who published The Girl in the Flammable Skirt in 1998, was at the start of a wave that has come to include authors such as Ramona Ausubel, Karen Russell, Helen Oyeyemi, Carmen Maria Machado, Samantha Hunt, Nona Caspers, Daisy Johnson, Amelia Grey, Suzette Mayr, and many others. It’s notable, of course, that these authors are overwhelmingly women. There are men writing in the genre — Kevin Brockmeier’s 2002 O. Henry Award-winning short story “The Ceiling,” about the dissolution of a marriage as the sky begins to lower, is an excellent counter-example — but it is a mode that’s ideally suited to capture the inherent strangeness of a marginalized experience. Recently, this has given us a number of collections and novels that use fabulism as a way of speaking to queerness. Surrealism — the queering of reality — has become a tool for accessing or depicting the reality of inhabiting a queer body.

Around October of 2017, just as the National Book Award winners were set to be announced, Machado’s nominated collection Her Body and Other Parties was suddenly everywhere. Everyone I knew was talking about it, writing about it, recommending it, and teaching it. A collective horror had arisen around the so-called “husband stitch,” a medical procedure which was rumored to tighten the vagina again after birth — and the title of the first story in Machado’s collection.

On the surface, it’s about the raw sexuality of a young woman who falls in love, marries, and has a child. She wears a ribbon around her neck, which she forbids her husband or son from ever untying. In reality, it’s more complicated. An old professor of mine, who assigned the story to a class of undergraduates, told me that there was a gulf between students who knew the fairytale Machado is quoting — a story I first encountered as “The Green Ribbon” — and those who didn’t. The divide, she said, was more or less along gender lines. Boys, on the whole, were oblivious to the implication of the ribbon, while the girls, for the most part, knew what was coming. I had never considered the original to be particularly gendered, but it helped me consider the story as a coded cautionary tale. Machado uses the green ribbon as a way of accessing some knowledge that women share: that even “good” men want what they are not offered, and that women — like those that the narrator encounters with their own ribbons — live daily in fractured, vulnerable bodies.

Machado periodically interrupts the narrative to discuss various fairytales, and places an emphasis on oral telling by including directions on how to read the story out loud. These push the reader toward the seam in reality that Machado is interested in opening. It encourages an allegorical reading familiar from fairytales and fables, and uses the fantastic as a way to access the real. Machado does something similar in the novel’s more overtly queer stories. “Inventory,” for example, catalogues the narrator’s lovers through a post-apocalyptic event. The catastrophe, however, is only used to turn a magnifying lens on the diversity of her desire — for women and men, sometimes both at once. In “Real Women Have Bodies,” a girl working in a mall dress shop begins a sexual relationship with the woman who makes deliveries. As their relationship deepens, they discover that the bodies of women and girls are randomly fading out of existence. Though it’s possible to read this as an allegory for the ordinary violence committed against queer and female bodies, Machado uses the epidemic to access the urgency of queer relationships, and to comment on what it means to be a titular “real woman” as a lesbian.

Helen Oyeyemi, a British writer of Nigerian descent, also has a fascination with the strange, which she employs to talk about race, colonialism, and adolescence. Her novel White is for Witching follows a young woman afflicted by pica — a psychological disorder defined by a compulsion to eat non-food things like dirt, paper, hair, or, in the case of Oyeyemi’s Miranda, chalk. The compulsion ties her to her family’s land and the house she lives in, which both haunts and is haunted by Miranda. The novel is full of twins and opposites, spirits, and Haitian voodoo, but also has, at its heart, a sweet romance between Miranda and Ore, a Nigerian woman studying at Cambridge.

For Oyeyemi, the gothic haunting — which recalls Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher” — is a way of expressing some of the disquietude of adolescence and the struggle to understand oneself in relation to the external factors that shape our lives as adults: family history, race, trauma. Living in a haunted house stands in for or represents the parts of adolescence that are baffling, horrific, or alienating — but Miranda’s relationship with Ore exists in spite of those things and as an antidote to them. The haunted house abstracts the real violence that queer adolescents are subject to, and offers another avenue for readers to occupy that experience.

These women have hit on the strangeness of occupying a queer or female body, and they’re making the world around those bodies strange as well.

Daisy Johnson, in her debut collection Fen, also uses a haunting to speak to the queer experience. In “A Bruise the Shape and Size of a Door Handle” a young woman is caught between the house that loves her in increasingly violent ways and a female classmate. The physical house, ever a stand-in for the more abstract idea of a home, is both hostile and tender. Johnson, a British writer who makes a character of the fens where she lived as a child, is clearly fascinated by the uncomfortable, impatient coming-of-age of teenaged girls. A theme of consumption runs through the stories: in one, a girl refuses food until she grows so thin that she becomes an eel; in another, a house full of languid but restless teenagers seduce men and eat them. All her stories get at the strangeness of adolescence, and Johnson has a knack for making the cocktail of desire, fear, and boredom strikingly tangible.

Her new novel, Everything Under, released in July and recently nominated for a Man Booker, is an intimate look at language and motherhood, but with a physical manifestation of terror that manages to straddle the line between obviously real and a product of the imagination. The novel expertly weaves between the present, which follows the lexicographer Gretel as she searches for and is reunited with her mother Sarah, and a past in which mother and daughter are stalked along the canals of Oxford by something predatory in the water. Perhaps most fascinating are the two trans characters, Fiona and Marcus, who play out a Greek tragedy in what begins as the secondary plot, but is quickly tied to the uncanny disturbance. The surrealistic elements of the original Sophoclean story, which includes a prophecy, feel integral to Marcus’s process of transition and the fatedness of eschewing his dysmorphic body for an identity that feels more honest. “The way we will end up is coded into us from the moment we are born,” Sarah says, a sense that’s intensified by the novel’s dreamy terror.

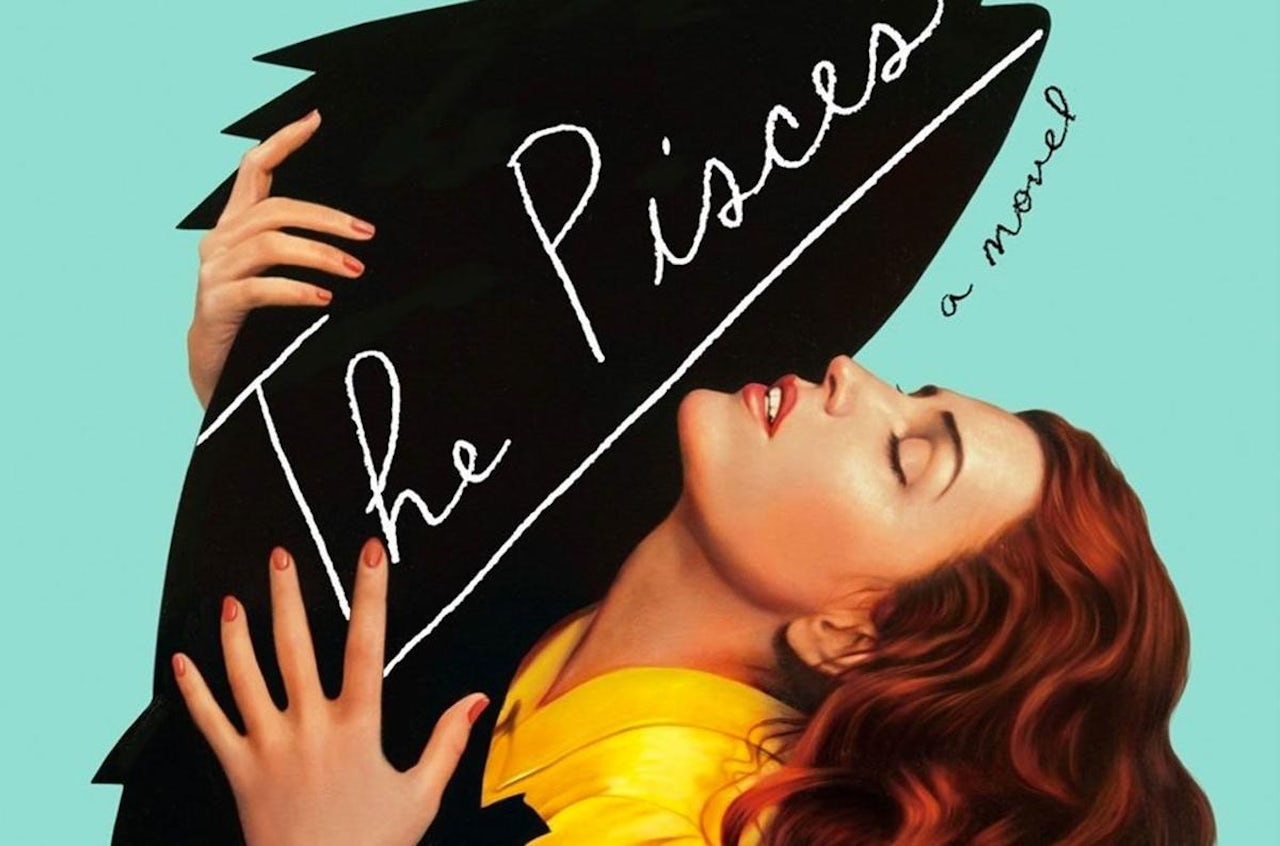

One of the most rewarding things about pursuing this trend in contemporary literature is the sense that the category is ever expanding. The last year has been full of fabulist writing. Suzette Mayer used a haunted building on a college campus to talk about anxiety, queerness, and race in academia in Dr. Edith Vane and the Hares of Crawley Hall. Samantha Hunt’s The Dark Dark featured, between meditations on the strangeness of pregnancy and motherhood, a story about a woman who turns into a deer at night as a way of processing her relationship to her body following an extramarital affair. (Tin House is re-releasing her incredible novel The Seas this summer; it’s a haunting, shifting novel about the consumptive intensity of adolescent love, dictionaries, and mermaids.) Nona Casper’s novel in stories, The Fifth Woman, out later this year, uses fabulism to depict a woman’s grief following the death of her girlfriend. Melissa Broder’s explosively popular novel The Pisces used a relationship with a merman to talk about womanhood and emotional nihilism. These women have hit on the strangeness of occupying a queer or female body, and they’re making the world around those bodies strange as well.

We’re entering a moment of increased attention to diversity in art and entertainment. More queer narratives seem to be released every year, and with those — whether they appear on TV, in movies, or in stories and novels — queer representation (good and bad) is becoming more common. But we also find ourselves at a time when our awareness of intolerance is high. New media has allowed for increased attention to and organization around women’s rights, violence against people of color, and discrimination against queers. And it’s unfortunately not just our attention that has increased: since 2016, hate crimes have been steadily rising. The tension between those things — increased visibility and at the same time, increased violence — needs release, and fabulism is a way of accessing and depicting that in-betweenness, that strangeness.

Before this spring’s sudden loss of Zach Doss, a former editor at Black Warrior Review and an incredible fiction writer, I was extremely fortunate to see him on the 2017 AWP panel Fractured Selves: Fabulism as a Platform for Minorities, Women, and the LGBT Community, speaking along with Aubrey Hirsch, Sequoia Nagamatsu, and Brenda Peynado. “Fabulism is a lever to get in a crack and express something that can’t be expressed in any other way,” he said, a statement that’s lingered with me. It’s perhaps what Bettelheim and Heuscher were getting at: Sometimes, there’s no other way to understand the disorientation of childhood except through the red hood, the grandmother, and the wolf. Sometimes the experience of queerness demands a haunted house.