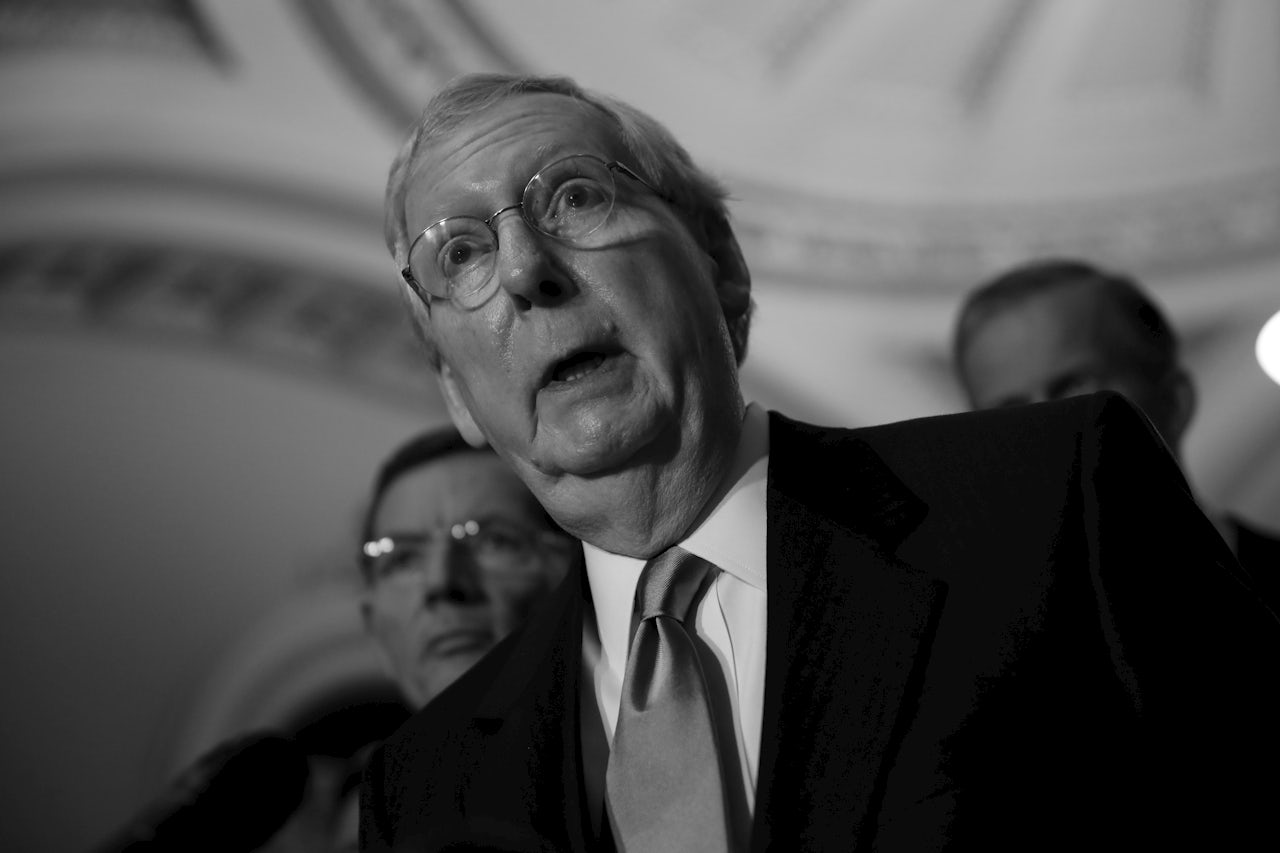

The U.S. Supreme Court has a new vacancy thanks to the retirement of Justice Anthony Kennedy. And Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell is ready to shepherd the Senate into expediently performing its Constitutional duty of vetting and voting on President Trump’s nominee — we’ll likely find out who that is fairly soon.

With a bitterly partisan nomination process looming, pundits have been somewhat vainly attempting to draw a straight line through Sen. McConnell’s recent years of scattershot judicial-nominee logic. Critics say the election-year reasoning Sen. McConnell employed in his 2016 obstruction of President Obama nominee Merrick Garland might give Democrats proper justification to derail Trump’s nominee in 2018, while others maintain that the “McConnell Rule” (or is it the Biden Rule?) only applies during presidential election years.

But it seems the only consistent judicial principle Sen. McConnell has practiced throughout his career has been one of political expediency. And he’s done it very well.

Before successfully blocking Garland’s appointment, the six-term Kentucky senator voted to reject Obama’s two SCOTUS appointees, Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, primarily on ideological grounds. Sen. McConnell and fellow Senate Republicans held up dozens of Obama’s lower-court nominees for similar political reasons.

Yet in 1987, during the confirmation process for Reagan nominee Robert Bork, a fresh-faced Sen. McConnell asserted that senators should leave aside a prospective Supreme Court justice’s political leanings when considering their qualifications. (The Democratic-controlled Senate would go on to reject Bork, a staunch judicial conservative, and later confirm the more moderate Kennedy — in a presidential election year, coincidentally.) In a humorous back-and-forth recounted in The Courier-Journal of Louisville, Kentucky, then-Sen. Joe Biden called bullshit on McConnell:

Biden, in an effort to shake McConnell’s argument, asked if the Kentuckian himself were president and all nine Supreme Court members resigned at once, would it be appropriate for him to appoint only conservatives. McConnell said it would be, replying that there is nothing in the Constitution that says the court must have an ideological balance. Does that mean, Biden continued, that McConnell would vote to confirm a Communist if one were nominated? McConnell said no because a Communist would be dedicated to overthrowing the government. … When Biden continued with another question, McConnell excused himself, saying he had a meeting to attend and that “I’m sure this debate will continue.”

Sen. McConnell’s shifty precepts aren’t limited to Supreme Court nominations; he has changed his position on testy issues ranging from abortion to collective bargaining. In The Cynic, his biography of the senator, the journalist Alec MacGillis describes a young Addison Mitchell McConnell Jr. who initially ascribed to a “liberal Republicanism” that was supportive of the civil rights movement. Sen. McConnell won his first elected post as chief executive of Kentucky’s Jefferson County partly by earning the endorsement of the local AFL-CIO labor union, and while in office he charmed pro-choice advocates as he routinely rebuked anti-abortion legislation.

So what happened to Woke Mitch? MacGillis points to the 1984 election as a turning point, when the senator rode into office on Roger Ailes’ win-at-all-costs chicanery and President Reagan’s conservative “coattails:”

Leading up to and during his campaign, the [moderate-leaning] Ripon Society’s political arm, the New Leadership Fund, had touted McConnell as a moderate Republican on the rise. But on arriving in Washington, he confounded such expectations. … And, to the dismay of [former director of the Kentucky chapter of the ACLU] Jessica Loving and his other abortion rights allies in Louisville, McConnell flipped to the pro-life side on votes such as blocking Medicaid funding for abortions in cases of rape or incest. (Years later, Loving ran into McConnell at a cocktail party at the University of Louisville and told him, “By the way, I’ve never properly thanked you for what you did—you were the best elected official for the pro-choice issue,” to which, she recalls, “he got this pained look, his face got paler than usual and his lips got thinner than usual and he said, ‘You know, I don’t really want anyone to know that.’ ”)

The upward trajectory and longevity of Sen. McConnell’s career is underscored by his calculated habit of assuming politically convenient postures when necessary. And though he’s the longest-serving senator in Kentucky’s history, the project of politicizing the Supreme Court might prove to be his most enduring legacy. “One of my proudest moments,” Sen. McConnell told a crowd at an August 2016 rally, “was when I looked at Barack Obama in the eye and I said, ‘Mr. President, you will not fill this Supreme Court vacancy.’”

Sen. McConnell delivered this line with uncharacteristic pep, as though he had written and rehearsed it beforehand. Then he paused and briefly waited for the cheers that he knew would follow.