Ready Player One is an enjoyable movie, I’m surprised to say. On Friday night, a companion and I settled in for the evening show in a packed theater, mildly intoxicated and hoping for a dumbassed time to tell our friends about. It was the perfect use of MoviePass: to watch something we’d never, ever pay for. And then about halfway into the two hour runtime, I leaned over and whispered, “I think I enjoy this,” shame flickering in my heart as I realized how dismissive I’d been for really no good reason at all.

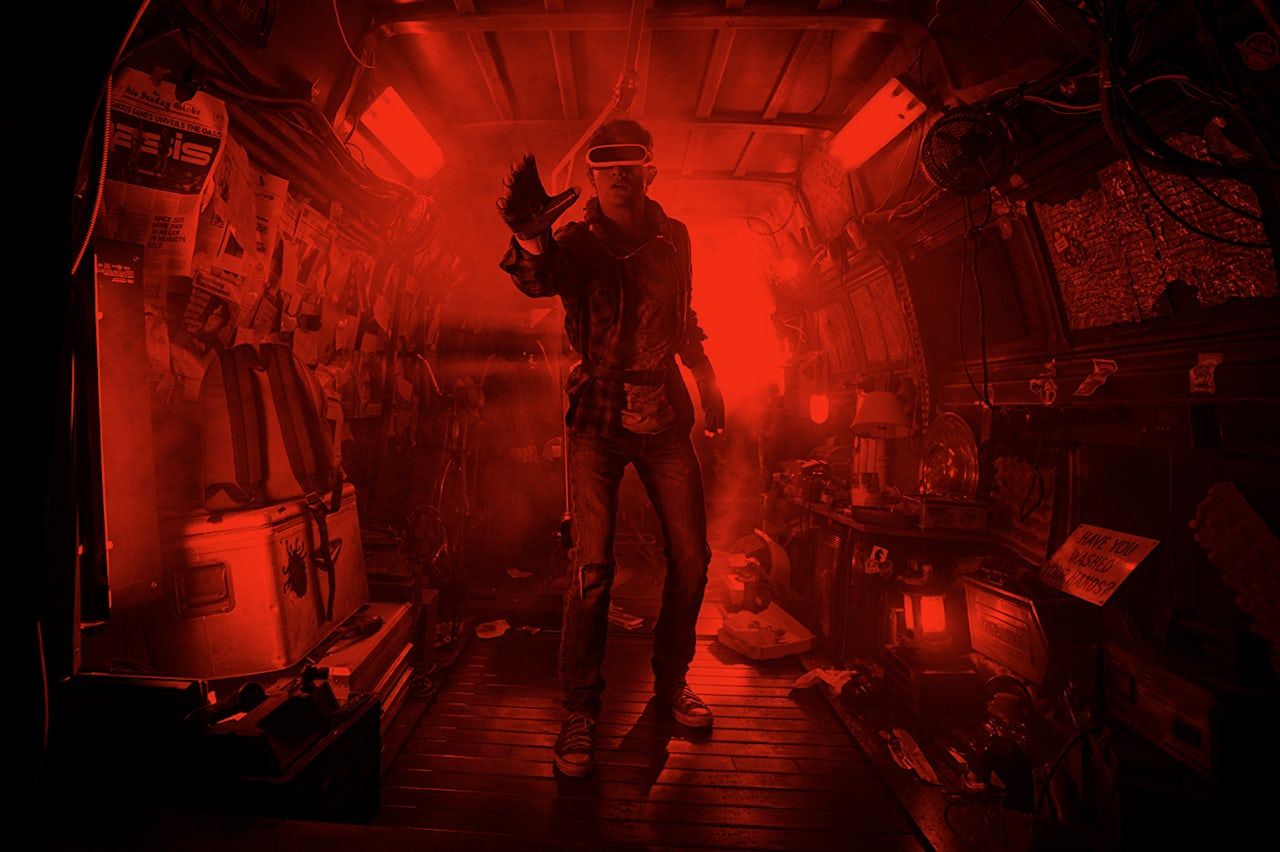

Ready Player One is a Steven Spielberg adaptation of the popular Ernest Cline novel, which received generally positive reviews upon its release in 2011. It’s the story of Wade Watts, a teen in a not-so distant future where most of the people on Earth are avid users of a full-body virtual reality simulator called The Oasis. Outside the Oasis, Wade is a nondescript kid living in a trailer park with his redneck aunt and her deadbeat, abusive boyfriend. Inside, he is Parzival, owner of swooshy anime hair, and a cadre of cool-looking best friends who are attempting find three keys coded into the game by James Halliday, the late creator of the Oasis. Whoever finds the keys gets control of the Oasis; Wade and his friends want to do this before IOI, a shadowy corporation, so that the only happy thing of the dystopian future won’t be controlled by the most obviously villainous people possible. (Some light spoilers follow from here.)

This is all standard for genre fiction, but Ready Player One’s most infamous quality was its emphasis on the past. The future stinks, so Wade openly pines for the world he never knew. His perspective on life is entirely informed by his infatuation with ‘80s culture — the culture Cline grew up on — which is reflected in the hundreds of references made through his narration and shown in the Oasis, a place where players can do anything they want, and settle for watching Batman fight Freddie Krueger inside of a Death Star.

How this book was positively reviewed is confusing, as Ready Player One is an awful book. It’s garishly written, saturated with unnecessary allusions and narratively obvious — everything goes the way you’d expect a hero’s quest featuring an earnest white teen to go. When the trailer dropped, the movie was pre-judged for its connection to Cline’s novel. Many observers and many websites, including this one, assumed the film would be — for lack of a better phrase — the worst shit ever.

In retrospect, it was unwise for people to not give Spielberg — one of the greatest ever at melding widescreen action with childhood pathos — the benefit of the doubt. Many of the book’s flaws have been fixed by the switch in medium: There is none of Cline’s cloying narration (the sole voice over comes in the opening sequence), and most (though not all) of the references are only background eye candy, there for the viewer to pick out or ignore as necessary. In Spielberg’s hands, the nerdy nostalgia coating every page of Cline’s novel is closer to ambient texture, in service of an intriguing sensory exercise: What would it feel like to live inside of a video game?

I’ve played video games, as they’ve progressed from niche hobby to dominant mainstream entertainment, for most of my remembered life. All the while I’ve searched for a perfect game, which to me is a game where I can do anything I want in a completely immersive environment. (Grand Theft Auto III fit the bill; so did The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim.) In reality, I haven’t played the perfect game because the technology doesn’t exist. No matter how souped-up the graphics cards, or how intricate the underlying mechanics, I’ll still be holding a controller on my couch. Virtual reality gets us closer, but the present games are limited by their relatively imprecise controls, as well as their lack of conceptual ambition.

Ready Player One is the most absorbing depiction of this ideal “perfect game” that I’ve ever seen. Inside the Oasis, every player’s real life activity is mirrored by their avatar, with no delay in response time. There are no clunky buttons required for organizing one’s equipment; you only touch a screen in the air, and swipe through the options with your hand. And instead of being limited to one specific locale — say, a grimy city or an epic fantasy world — every possible world is available for exploration. If the movie offers pleasure, it’s from the transference of placing yourself inside the Oasis, imagining what it would be like to be one of its players.

There is an astonishing sequence, early on in the movie, when the players race cars on a dangerous track mocked up to look like New York City, in order to reach the first key. While Parzival bobs and weaves around all the traps and competitors, we’re alerted to King Kong hovering over the city, ready to pounce on anyone approaching the finish line. He eventually figures out how to beat the level by bypassing it, speeding through a series of underground neon green pathways showing the framework undergirding the virtual track. As he drives, we see the rendered world above him playing out as expected, with Kong destroying the buildings and cars. We see the game and the delicate architecture empowering it, enabling us to better appreciate Halliday’s creation as a marvel of aesthetic experience and technological prowess.

Broadly speaking, the movie is most pleasurable when it pushes us to think about creation and the act of creation. There is a delightful scene where Parzival and his friends must play through one of the greatest ever horror movies rendered as a video game level. The fan service isn’t so bad, either: There’s also a much advertised, very fun fight sequence where every character ever teams up to duke it out on an icy battlefield, including a tribute to Japanese culture far superior to Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs.

The seams begin to show when the movie tries to think about anything other than gaming. The environmental degradation forcing everyone into trailers stacked on top of each other is never remarked upon; neither are the physical conditions of these millions of citizens who spend all their waking hours strapped into their rigs. What happened to the world, to make it this way? We never know. Wade falls for Artemis, a female player, who warns him he might be disappointed by her in real life… only for the movie to eventually reveal she’s an attractive white woman.

IOI signs up hundreds of gamers into indentured servitude for debts incurred playing the Oasis, but despite a half-hearted “rebellion” storyline, the extent of their power is never explored. The social alienation of the Oasis’ players and creator, who spend all their time in a fantasy world, is addressed with some melancholy, but this open wound affecting the future — and, you might say, the present — is quickly bandaged by a milquetoast reminder that reality is the only real thing. Were it so easy!

The Oasis represents anything and everything to its players, which means it can also represent a big nothing. Take, for example, the long-teased presence of the Iron Giant, who’s unleashed in the climactic battle scene. Given the anti-violence stance of the source material, is it crass to show the robot breathing electric fire and smashing enemies? Is the crassness meant to be some kind of meta-commentary on how fans will often co-opt the characters they love in ways the creators would never agree with? Or is the Iron Giant only there because it looks badass? Is there any meaningful way to make sense of a world without limits, or is it just one big fanboyish jerkoff for the easily titillated?

The film flirts with these notions while remaining ever so slightly on the sidelines. This, in some sense, is due to the format: Ready Player One is meant to be a popcorn action movie, not a treatise on the way we live. The dark side of digital escapism, the prevalence of urban congestion, the way capitalism forces us to literally sign away our bodies — these are all immensely relevant ideas whose inclusion hints Ready Player One may even be a smart movie… until it isn’t.

On the other hand, demanding thoughtful politics from what’s essentially artful fan service is what got us into the mess we’re in now. In the six years since the book came out, mainstream movies have become increasingly composed of stuff you already know, known mostly by nerds. The abundance of superhero movies and stories spun out of shallow intellectual properties (Rampage, Battleship) have rendered the release calendar impenetrable to anyone who didn’t spend large parts of their childhood in a comic book store or arcade. And because so many of these movies have the veneer of serious art, audiences and critics rush to proclaim unearned value and over-analyze material that, at the end of the day, is mostly dudes in suits punching each other. (Eighty-nine percent of critics approved of Doctor Strange, but could you ever recommend it to a human being?)

For a movie to be spun wholecloth out of this dramatically rendered remember when? seemed like a most highly scoffable offense, and so Ready Player One was readily pre-judged by audiences beginning to realize they’re sick of all this shit. It may have appeared to be the ultimate nadir of a pop culture more interested in referencing itself than making something new, but because the movie is nowhere near as dismal as critics guessed it would be, the reviews have been mostly positive and the box office returns generally encouraging. The pendulum has yet to swing back, and the most cynical interpretation would suggest studios will gleefully latch onto whatever the next craven pop cultural hodgepodge emerges from the ashes of fanfiction.net.

It’s true that the superhero adaptation industrial complex has produced a lot of mediocre art. But I think it’s also unhealthy, in a different way, to be so consistently attuned to the missteps of this work, as is going to be natural for consumers who are very suspicious of the forces trying to suck up their attention. That Ready Player One is obviously not the worst shit ever makes the fussing seem, in retrospect, pretty stupid. If the discourse often feels like a giant game, its fragility is revealed when one side refuses to play its part as expected, and it behooves everyone to de-escalate where possible — to call a rose a rose, or a popcorn movie a popcorn movie.

Toward the end of the movie, we see the room where Halliday grew up, as his adult avatar poses next to a representation of his childhood self, surrounded by all his favorite books and games. It’s a nerd’s paradise, but it’s also sad to see how this grown man spent his entire life pining after the comforts of his childhood. But given the option to walk away from this kind of idle fantasizing forever, Wade just decides to fantasize less. It’s an underwhelming payoff, given that freedom from the system is just in sight. But it’s a more honest admission that achieving true awareness of the world around us might occasionally pale to the thrill of watching Batman fight Freddie Krueger inside a Death Star, however basic it might make us. Everyone needs a little respite from the real world.