Very Intriguing Person

is a series about people who fascinate us, for better or worse.

The sweaty nightmare of the modern internet user is something called “context collapse.” It’s a phenomenon unique to social media where, say, you do a post like “White genocide is good” for your friends. Somehow, it leaves your circle and is presented to a wider audience as a sincere opinion without the context of mitigated irony. After this context collapse, it’s nearly impossible to try to reapply the original meaning; you’re trying to put the toothpaste back in the tube. And so now, unlucky for you, thousands of strangers believe you’re the person who thinks white genocide is the one true way.

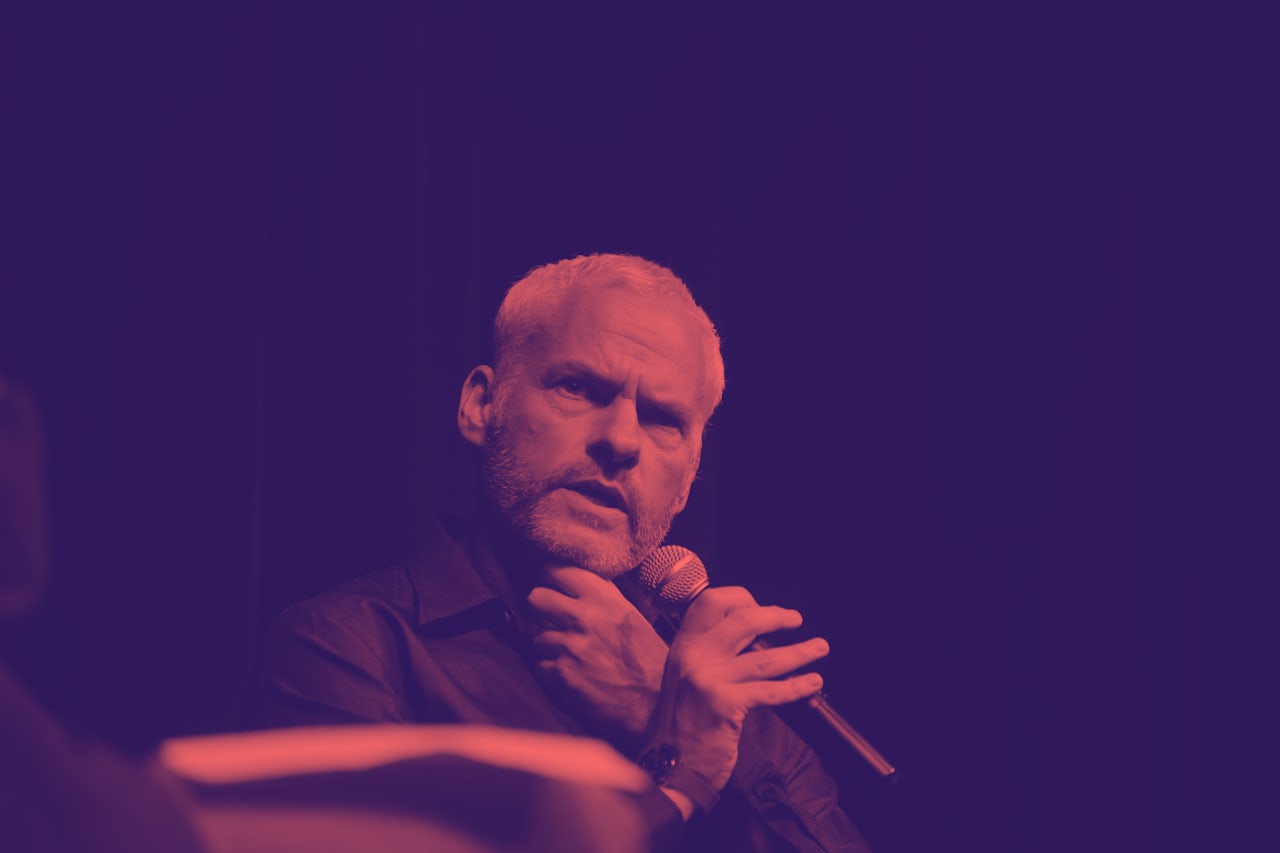

The latest movie from British writer and director Martin McDonagh, the much fêted and criticized Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, is the odd film that invites context collapse throughout. An inconsolable mother (Frances McDormand) takes out an ad across three billboards on the outskirts of a small, fictional town as a method of shaming the police department for not yet solving the gruesome rape and murder of her daughter. But as townspeople juggle one moral conundrum after another, the film’s treatment of rural Midwest America with regards to its cultural artifacts, race, and mountains (?) is so bafflingly incoherent it almost torpedoes what is otherwise an intriguing, stunningly well-acted movie about inherited trauma and a mother’s frayed ends of grief. The film is a pancake stack of unreal locations acting as a localized milieu, haphazard plotting that is also quotidian in its detail, and offensively drawn characters acting alongside deeply layered ones. It is the collapse of the real and the absurd and I think it is a fascinating film that lives singularly and squarely between awful and wonderful.

Context is like a social compass. It guides our politics, our reasoning, our decisions to get mad at bad articles online, but its function in storytelling is a little less strict. So as to prevent looking like an idiot, we demand context to understand why things happen. Crucially, though, it’s not always an artist’s job to provide this for an audience. The need to read fiction as reality and overlay it with a real-life ethical or moral context collapses the space in which fiction is allowed to exist (the receiving of the hyperreal, viral New Yorker short story “Cat Person” as just another personal essay comes to mind). Context, above all, helps create a reality that we can understand and feel comfortable living in. But what about the emotions fiction can create when a writer purposefully allows context slip away?

Martin McDonagh has always had a touch-and-go relationship with context, choosing, as many filmmakers and storytellers do, to flatten it out it in service of something more dramatic. “Never let the truth get in the way of a good story,” the canard goes, and it’s one McDonagh has followed his entire career as a dazzling lyricist, pitch-black humorist, and someone for whom the political context comes secondary to having his richly drawn characters say “cunt” a lot. Like the plays of the acerbic Harold Pinter or the avant-garde Samuel Beckett before him, McDonagh’s characters are vulgar fools and sage old men that function more like chess pieces in some ambiguous theatrical universe, a mode that becomes very confused in his films. The awards so far given to Three Billboards juxtaposed with a few salient dismissals has made me wonder: Is McDonagh missing our context or are we missing his?

His plays and films are about recognizing the hatred we harbor in our psyches for ourselves and for others. How do you develop a proper context for that?

Like many people, I left Three Billboards feeling unsettled about its bathetic ending(s), its careless handling of its black characters, and its utter disregard for time and place. Since becoming familiar with McDonagh’s plays when I was a young, impressionable kid who thought provocateurs like Chuck Palahniuk and Quentin Tarantino were brave because they used profanity liberally, I’ve often hailed McDonagh as one of my favorite playwrights. McDonagh, who was raised in London the son of Western Irish parents, likewise had a laddish interest in the hypocrisies of social norms, authority figures, and cruelty as a shock device. He was a choir boy in a Catholic parish and grew up steeped in the stories of Irish nationalism, but as he began to develop his voice as a writer, those influences faded to the background. His writing became hyperreal, chiefly concerned with language, wit, and tying his deeply human characters in agonizing ethical knots just to see if he could write them out of it.

His early plays were set in the West of Ireland, and to me, a theater major from Wisconsin (or to any lay British or American audience) their authenticity seemed unassailable. McDonagh’s first collection, referred to as “The Leenane Trilogy” — The Beauty Queen of Leenane (1996), A Skull in Connemara (1997), and The Lonesome West (1997), all conceived and written when McDonagh was 24 — is filled with torture by hot oil, daughters murdering their mothers with pokers, sons murdering their fathers over slight insults, and a man uncovering the bones of his dead wife — whom he may have killed — in a graveyard. All the great Irish institutions of religion, family, and national pride are subverted with the flick of McDonagh’s pen, evanescently dismissed as a morbid joke or roundly stripped of their haughty importance.

These plays felt both romantic in the way that the Irish poet and playwright John Millington Synge wrote rapturously about his Ireland in the early 20th century, and authentic because of their caustic cynicism and use of the Irish dialect as its own musical instrument. It’s a world of self-possessed and dispossessed “shite-gob’d fecks” where a priest claims “God has no jurisdiction,” and later goes on to drown himself in a lake, a marginalized but unreal place of poteen-drinking degenerates who wield vengeance and forgiveness with the same reckless, melodramatic flair. The oppressive poverty and violence of rural Ireland is not on trial; it’s only the inhabitants who are to be judged and redeemed.

As McDonagh’s star rose as the reigning bad-boy of Anglo-Irish theater, some critics began to question his slippery relationship to historical context. His 2001 play The Lieutenant of Inishmore is a revenge tale about a fanatic member of Irish National Liberation Army (think the IRA but more radical and Marxist) who kills and tortures three other paramilitary members because he believes they killed his cat (think John Wick but this guy dismembers his victims on stage). It is a madcap and ludicrously violent play about the hypocrisy of violence, but placed in the context of post-colonial Ireland and the politics Republican paramilitarism, it doesn’t really hang together. Because he’s chiefly concerned with farce, cutting dialogue, and shit-happens plotting, McDonagh only loosely interrogates the history of Republican tactics or its justification of violence. In her critical essay “Selling (-Out) to the English” the writer Mary Luckhurst questions the slipshod political backdrops of his plays and as a British-born citizen, accusing McDonagh of “colonially derived propaganda” using broad Irish caricatures “who merge into a single cod stereotype of ‘Oirishness.’”

It’s when McDonagh brings this context collapse to America that his stories undergo a sharper and more potent kind of scrutiny from American critics and audiences. McDonagh has set two of his works in the States, the first a play called A Behanding in Spokane (which, incidentally, doesn’t take place in Spokane, but rather a fictional town called Tarlington in an unspecified location). The lone black character, fucking called Toby, is referred to by every slur in the book. Racism and especially homophobia is a constant in McDonagh’s work, as is ableism, sexism, and all manners of political incorrectness born of the boorish Tartuffian characters he tries to rend pathos out of. Under the guise of theatrical farce, McDonagh gets a bit of a laugh for breaking taboos, but when examined under the political context of a British-born heterosexual male consistently using marginalized characters as the butt of jokes in these increasingly jumbled contexts, it becomes less of comment than it does a crutch. It was time, then, that the author and New Yorker theatre critic Hilton Als opened his review of A Behanding in Spokane with, “I don’t know a single self-respecting black actor who wouldn’t feel shame and fury while sitting through Martin McDonagh’s new play.��

No doubt that McDonagh’s works are less about the dramaturgy behind it and more about the broader theatrical themes of fate, like the drunken lots of Eugene O’Neill’s melodramas but with more dwarfs railing lines of cocaine and talking about race wars. But by this year’s Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri — his second work set in another fictional American town and by far the one that has garnered him the most acclaim and widespread attention — it had me wondering whether all this was just sloppy writing (the pairing-off of two ancillary black characters is non-negotiably awful) or if it was in fact a choice to continue to strip context out of his stories so that it could allow us to live in the the idea of a violent, Trumpian small-town America. The arc of McDonagh’s moral universe doesn’t bend toward justice; it bends towards violence and retribution. His plays and films are about recognizing the hatred we harbor in our psyches for ourselves and for others. How do you develop a proper context for that?

In Three Billboards, the audience is asked to develop pathos for and forgive two people. The first is Mildred (Frances McDormand), whose daughter was, as one of the billboards reads, “Raped While Dying.” The second character is Officer Dixon (Sam Rockwell) a racist clown whose history of “persons of color torturing” and modern-day defenestration of teens has lost him the respect of his fellow officers. Spoilers follow, but after half of his face is burnt off in a fire, the disfigured Dixon now feels that redemption for his sins can come by way of helping Mildred. So, he does some ad-hoc DNA collection in a bar after he overhears a couple guys talking about defiling a burning corpse. The movie has more twists and turns than an entire season of Scandal, and by the end, McDonagh — if not spiritually, then cinematically — puts Mildred and Dixon on equal moral footing. They are on the same path towards justice as they ride off into the sunset to seek out their own.

It’s an unsatisfying ending, but McDonagh has never been fond of tidy ones. Just like In Bruges leaves us wondering whether Colin Farrell’s barely redeemed hitman character lives or dies, with Three Billboards, we’re left to ponder the relationship of Dixon and Mildred. McDonagh hastily solves for their sins and virtues, and presents them both as some intellectually balanced equation. It doesn’t reveal anything about the larger systems of justice and redemption — whether a cop who tortured a black prisoner deserves sympathy or the ends to which a grieving mother can seek justice — but rather it feels like McDonagh uses Dixon’s racism and Mildred’s cruelty as a stand-ins for any kind of grand transgression: physical abuse, torture, rape, murder. It’s just another puzzle to try to solve.

But this is why his mise en scène is so decidedly off. Even in his films, McDonagh’s scripts hew closer to Pinter’s 1967 play The Homecoming or Beckett’s Waiting For Godot than Tarantino or the Coen Brothers, as he is often compared to. The worlds he build appear real, but it’s just a scrim to take you to a more sinister, stylized, fantastic place beneath the surface, where scabrous boys are allowed to test the limits of a real Catholic God’s mercy without fear of judgment from an audience. In this sense, watching Three Billboards, it feels like you’re supposed to glean some larger metaphor out of this: The worst of us have the capacity to change; a pernicious hatred has seeped into the soil of America; behold the power of advertising. It’s not lousy with metaphor as another film from this year — Darren Aronofsky’s mother! — is, but in its effort not to be heavy-handed, its slippery context and sense of place has welcomed a real-life context imposed on it, as opposed to letting the world exist somewhere between the black and white.

For better or for worse, McDonagh’s plays and films want to live in the space between, the moment where context collapses. I see a thin, cruel world created to entertain a thought experiment about restorative justice redeemed by the humanity sought so fervently by every character within it. It’s gum and nuts, together at last, and it’s that gnawing feeling that these characters all have such terribly strong desires that makes it so impossible to dismiss this world, as lazy as it is. Sure, it can seem at best cathartically unsatisfactory and at worst juvenile; “Some bad people are also good” could be a précis for McDonagh’s entire career. But his stories are all in service of the storyteller as a tradition — a reminder of the magic of suspension of disbelief and the new and unfamiliar emotions that can be felt when we live in a world a little askew from our own.

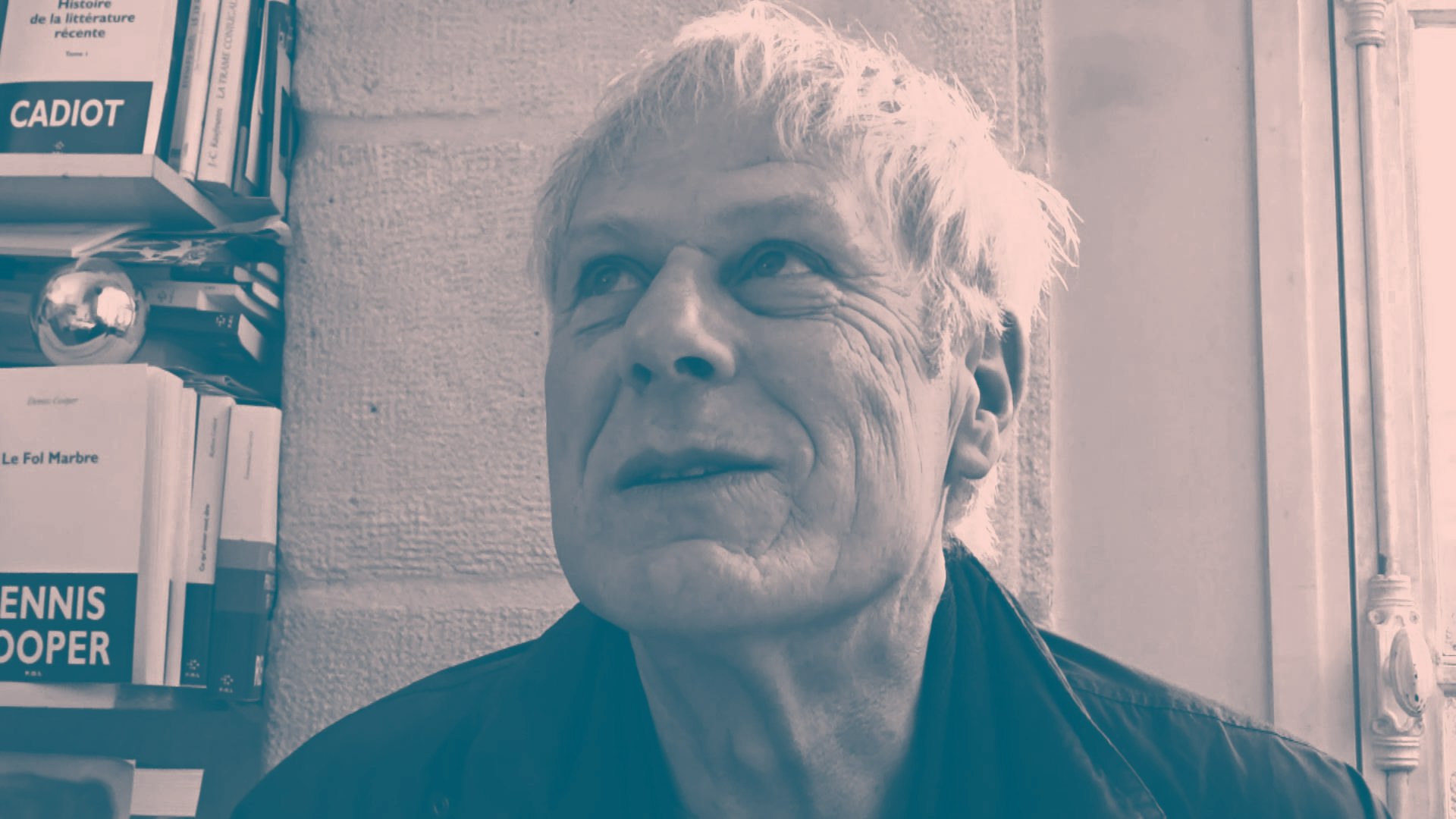

The real tragedy is that most people who are seeing Three Billboards are unfamiliar with 2004’s The Pillowman, McDonagh’s greatest work of his career. Not only is it is most deft and funny play that best deals with his long-running themes of inherited trauma and redemption, but it is his best perhaps because it takes place in a nameless, placeless totalitarian state and perhaps because it is about McDonagh’s greatest quality: storytelling. In the play, a writer is arrested for suspicion of being connected to a string of child murders and as he’s being interrogated, he lays out his writerly principles to the officers. One of them is: “I say if you’ve got a political axe to grind, if you’ve got a political what-do-ya-call-it, write a fucking essay.”