In the future, the canon of prestige television will expand to include shows without a conflicted white man as the protagonist, but as it stands it’s generally accepted the best shows of the 21st century are The Sopranos, Mad Men, Breaking Bad, and The Wire. I’ve rewatched all of these in the last year, partly because revisiting excellent art can be a more enlightening use of your time than waiting for some hyped new thing to get good — sorry, Stranger Things — and partly to see what I pick up on the second time around.

That said, I’m not sure if I’ve absorbed anything extra about The Wire other than a deepening understanding that it’s really, really good. (Also, there’s only one conflicted white man, and he’s barely the focus.) In the decade since it ended, The Wire is the only one of its peers to have accumulated the reputation of a show you really have to watch, for what it represents beyond good narrative television. For some reason, I thought this reputation might have the unintended effect of overrating it somewhat… but no, it’s just that good, filled with dozens of compelling characters and paced deliberately with no unearned emotional payoffs or cheap manipulations.

Beyond the particulars of its craft, The Wire is the most developed critique of American decline that has ever aired for mainstream consumption. To go through its five seasons was to receive primers on the problem of the war on drugs, industrialization, politics, education, and the media, all issues that remain part of the national conversation in 2018. To watch it signalled you not only as an aesthete, but an intellectual — someone who watched television because it was meaningful and instructive, not because it was entertaining. In the race to legitimize television as a serious art form over the last 20 years, no show has been a more effective tool for teaching you about the world, not just the dark heart of man. (Though there is plenty of that, too.)

And moreover, the show knew this; you were not supposed to watch because you wanted to see Omar spout one-liners. It was not supposed to be just another television show. “To be clear: I don’t think the Wire has all the right answers,” show creator David Simon once wrote in a blog criticizing Grantland for publishing a semi-serious bracket of the best Wire characters ever. “It may not even ask the right questions. It is certainly not some flawless piece of narrative, and as many good arguments about real stuff can be made criticizing the drama as praising it. But yes, the people who made the Wire did so to stir actual shit. We thought some prolonged arguments about what kind of country we’ve built might be a good thing, and if such arguments and discussions ever happen, we will feel more vindicated in purpose than if someone makes an argument for why The Wire is the best show in years.”

Perhaps fittingly, then, Grantland alum Jonathan Abrams has written All the Pieces Matter: The Inside Story of The Wire, a new book that’s the most serious attempt to contextualize the show as a Great One since its series finale. (It opens at a 2016 Columbia University panel about the show’s importance.) All the Pieces Matter takes its title from an episode in the first season, when the wise detective Lester Freamon is explaining to the oafish Roland Pryzbylewski why a seemingly innocent call they’ve picked up on the titular wire is related to the drug case they’re making. It is an oral history, for which Abrams talked to all of the show’s key participants, save for those who have died. It’s best consumed as a companion piece to the show, rather than a play-by-play.

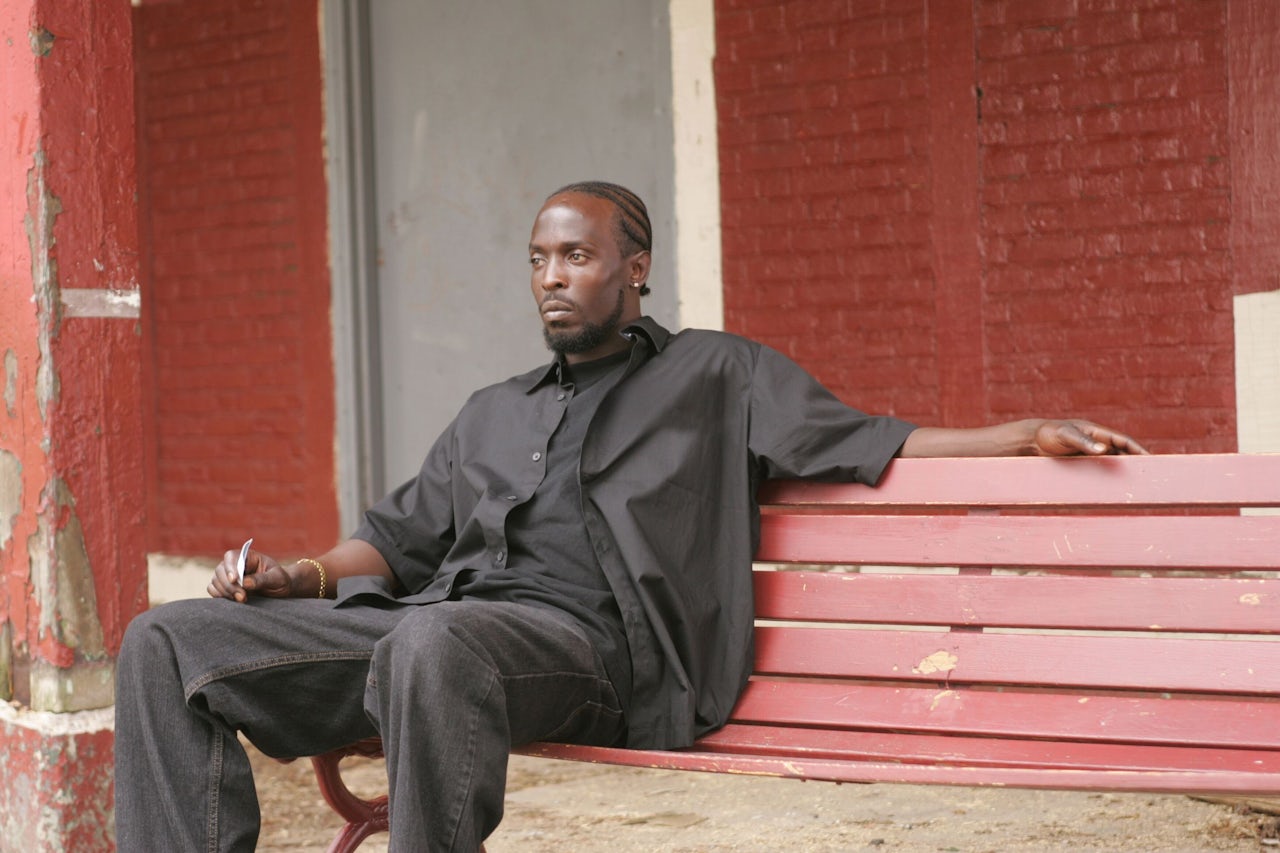

Abrams’ framing is not particularly revelatory. The show’s quality is presented as self-evident, recognized by every potential reader. The Wire was more of a Grecian drama than episodic entertainment; it did not quite fit with other character-driven HBO shows of its era like The Sopranos or Sex and the City; every season was devised as an exploration of a single premise. All of this is obvious enough, if you watch the show. Where he succeeds is the access, which he achieved thanks to the help of casting director Alexa L. Fogel, who convinced most of the principals of the book’s validity. Some of the actors haven’t held any prominent roles since The Wire, and presumably had nothing better to do, but Abrams got time with Michael B. Jordan, Idris Elba, Michael K. Williams, and several other legitimate celebrities. And because the show imbued so many of its characters with specific humanity that’s surprisingly difficult to find in dramatic television, it is simply nice to hear from so many personalities, all of whom have taken the time to think about why this show was so worthwhile.

Oral histories make their money by promising the story of what really happened without the writer’s commentary, and All the Pieces Matter gives us tasty anecdotes of the show’s occasionally contentious process. We learn about the actors who were pissed to find out they were being killed or written off, and which storylines were liked least by the writers. The title of the book confers a sort of divine purpose to every event, such as the shitty ride that gave Wendell Pierce the righteous indignation during his audition to win him the role as the righteously indignant Bunk Moreland, or the chance meeting between Williams and Felicia Pearson at a nightclub, whereby the untrained actor was cast in the role of the terrifying gang enforcer Snoop.

“I’m more interested in the arguments. I wish that were the legacy of the show.”

The Wire is also stereotyped as a show beloved by white people, used as a sort of shorthand to communicate a progressive thoughtfulness about its core issues. This kind of performative appreciation runs the risk of bizarrely blunting the show’s critical reputation, as many engaged cultural consumers hold a suspicious but not misunderstood view of anything too beloved by white people, such as kale or Portland. But the most thoughtful thing to come out of All the Pieces Matter is its treatment of diversity, which was not prized by the industry during its original run, nor marketed as one of the show’s virtues. “I never got the sense that it was a quote-unquote black show,” says Glynn Turman, who played the stubborn Mayor Royce. “But the question was: How did that happen? … And it’s because all of the characters were so multidimensional and so nonstereotypical.”

It was indeed rare to see a mainstream show with so many black actors cast in such diverse roles — heroes, villains, and the shades in between — that wasn’t explicitly marketed as a “black” show, a fact not lost on the players. During season three, Robert Wisdom, who played the empathetic police captain “Bunny” Colvin, organized a group photograph of all the black actors. “I was inspired by the Harlem musicians photo back in the day,” he said. “There’s some people who didn’t understand what we were doing. But I think everybody felt, especially with the twenty/twenty rearview, that it was really worth doing and they were proud that we were able to pose.” And as the criteria for the canon shifts to better venerate stories beyond the grim, white, male kind, The Wire is positioned to gain more kudos as a show well ahead of the curve in telling humanizing — but never cheapening — stories of the underprivileged, and the forces that keep them down.

Then again, there is some small sadness to a book whose ultimate goal is to demonstrate the show’s quality. “I’m more interested in the arguments,” Simon says at one point near the end. “I wish that were the legacy of the show.” But wrapping one’s head around the variables affecting the crisis in education, media, industrialization, and so on is much more complicated than appreciating a well-sketched character or cutting one-liner. And if it is easier to talk about how The Wire was unique for addressing these problems than actually addressing the problems — well, at the end of the day we’re talking about a television show.