In late January, a tweet went viral that was actually, somehow, interesting. It featured video footage of a Mario-style game that was hilariously difficult. “No idea what this game is called,” user @Steve_OS tweeted, “but whoever made it is the devil.”

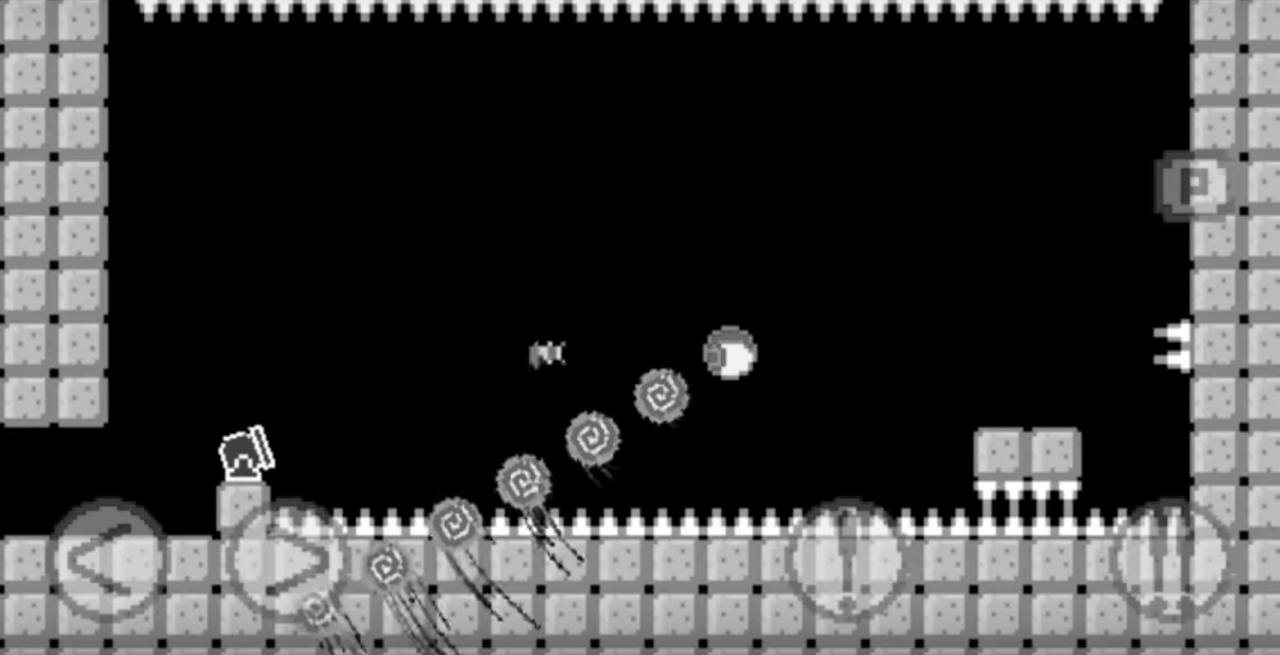

Basically, the player is presented with a series of pretty typical 8-bit side-scroller obstacles — platforms suspended over death pits, death spikes, and other assorted death ephemera — which the hero must navigate around. Except as they do so, the game actively fights back. A seemingly safe platform will unexpectedly sprout spikes. Should the player avoid that trap by jumping away at the last second, the game launches the platform at them. And so on.

The game is available for free, with in-game purchases, from Apple’s App Store. Called Trap Adventure 2, its description (translated from the Japanese) comes with a sardonic warning: “Caution!! This may be the most hardest, irritating, frustrating game EVER….” This is an understatement. Whereas most games try to offer a player a reasonable amount of time to respond to various threats, there’s no such chance for survival in Trap Adventure 2. It can only be mastered through constant death and rote memorization.

Actually playing the game is harder than the video makes it look. The touch screen buttons were imprecise and overly sensitive, compounding the already exceedingly obvious certainty for death. Not wanting to shell out for the full game, I was forced to play in “last chance mode,” which offers only a single life. Whenever I died, whoosh, I was warped back to the very start of the game, after watching a short advertisement for the less annoying mobile game Tap Titans 2.

The game is brutal and tormenting and infuriating. It’s barely fun. It’s a work of art.

あまりにも神ゲー… pic.twitter.com/DnRv5KG6UB

— 中段見てからしゃがむの余裕マン (@P_MEN876) January 22, 2018

Trap Adventure 2 was created by Hiroyoshi Oshiba, a mobile developer in Japan, who is (as far as I can tell) not the devil. He’s been working on a version of the game for a while, drawing inspiration from favorites like Mario, Paperboy, and Outer World. “When I was a child, I made a game that is the basis of [Trap Adventure 2],” he explains via email. “It was a game that only me and my friends played this time. So I thought, ‘Make a smartphone application, more people may play.’”

The game is meant to be more funny than hard. “I feel that I am childish,” he writes. “Children like to play naughty.”

His other games — the first Trap Adventure, and the appropriately titled Whoo! Sisyphus — have a similar goal: to offer unrelenting difficulty with a wink, as if to lovingly mock the nature of games themselves. Considering how intensely reactionary and toxic gamer culture can be, the medium probably deserves such treatment.

There’s a balletic beauty to someone effortlessly navigating a masochistic death maze.

Most games today are too easy. Blame capitalism. Making games tough was once a pretty reliable way to vacuum quarters out of the pockets of unsuspecting arcade teens. Conversely, a lot of modern games are now just platforms for advertisements and microtransactions. Games like Angry Birds 2 or Star Wars Battlefront 2 try to be accessible and addictive enough so that a maximum number of people will potentially get hooked and then be willing to pay to skip annoying levels or buy goofy hats for their in-game character. On the other end of the spectrum, marquee console games need to sell boatloads of copies in order to recoup their budgets, which means they can't punish the casual players who they hope will pick their game up.

Meanwhile, I can’t beat Trap Adventure 2. It’s just fucking impossible. And for this, I love it. The joy in “troll games” such as Oshiba’s is not derived solely by their sheer difficulty. Instead, they anticipate a player’s expectations, only to subvert them in surprising ways. Consequently, they’re deeply funny.

The genre peaked in popularity in the mid-to-late aughts. Trap Adventure 2 owes a lot to I Wanna Be The Guy (2007), a postmodern platformer known both for gleefully ripping music from classic games, as well as its relentless sadism. That was inspired by a Japanese Flash game released earlier that same year, The Big Adventure of Owata’s Life, which has an ASCII art aesthetic and similar maliciousness. There was also QWOP (2008), a simple track and field game complicated by incomprehensible controls. On the mainstream side of things, there’s the entire Metal Gear Solid series, which at one point (spoiler alert?) killed off its beloved main character just to mess with diehard fans of the series.

All seem to be spiritually linked to 1986 the NES game Takeshi’s Challenge, considered by some critics to be among the worst games ever made. Sure, the game is not “good” or “fun” in any conventional sense, but complaining about this stuff kind of misses the whole point. It’d be like criticizing John Cage’s “silent” composition 4’33” for being a dull pop song.

Takeshi’s Challenge was created by Japanese actor/comedian Takeshi Kitano, who allegedly came up with most of the ideas while getting plastered at a bar near the game studio. According to Den of Geek's retrospective, “It appears that the goal [of the game] is to break as many social mores as possible in order to obtain true happiness.”

How players accomplish this isn’t very clear. They can quit their jobs, punch their boss, divorce their spouse, beat up gang members, and sing karaoke (which involves actually singing into the console’s microphone until the game deems their attempts “good”). At one point they���re given a treasure map that appears blank until the player leaves the game controller untouched for an hour. A strategy guide was released, but it was filled with so many errors that it was essentially useless. That book’s author later died.

One of the most famous troll games is Desert Bus. It’s contained within Penn & Teller’s Smoke and Mirrors (1995), a collection of conceptually baffling minigames created by the megafamous illusionists which was intended for the Sega CD system but was never released. In it, the player has to drive an empty bus from Tucson to Las Vegas, in real time, without the ability to pause gameplay. It takes eight hours to get there. If the player gets tired and drives off the road, the bus breaks down, and they’re towed back to Tucson, also in real time. To prevent players from taping down the controller’s gas button, the bus veers slightly to the right, so the game requires constant attention. When you arrive in Vegas, you’re given a single point, and can drive back for another point.

Desert Bus has since reached cult status. A VR version was released in 2017, and there’s a gaming marathon called Desert Bus for Hope that plays the game to raise money for the charity Child’s Play. According to Desert Bus for Hope’s website, they’ve raised nearly $4 million.

I encountered my first troll game as a child, in the form of Super Mario Bros.: The Lost Levels. The game, a 1986 sequel to Super Mario Bros. which Nintendo initially deemed too challenging for American audiences, functions as a rebuke to anyone who enjoyed the original. Its challenges are self-referential and cruel. It begins almost identically as the first Super Mario Bros., except the first power-up mushroom that Mario encounters is now poisonous and instantly kills the player. For a six-year-old, this was vaguely traumatizing.

Over a decade later, I tried The Lost Levels again, during a particularly lonely first year at college. It was brutal, but I couldn’t stop. As I became adept at making my way through the game’s increasingly absurd levels, tapping into that state of focus-blackout that only great games provide, people started gathering in my dorm room to watch. When I finally beat it, everybody started cheering. Nerd bliss.

Perhaps the sudden popularity of Trap Adventure 2 is due to how people now consume games. They’re not just designed to be played, but to be watched. On Twitch streams, on YouTube channels, in viral tweets. There’s a balletic beauty to someone effortlessly navigating a masochistic death maze — it’s the joy of a dozen bored college students gathered around a small hand-me-down television watching a dusty old SNES game, but on a mass scale.

More than just great conceptual art pieces, there’s something invigorating about troll games, and difficult games in general. They make you scream and laugh and smash your equipment in rage. They unite us in a shared frustration. The alternative is settling for shelling out money for the right to poke at unsettlingly glassy pieces of candy, or watching crappy CGI movies that require the occasional tapping of an X button to prevent someone’s face from getting eaten. Who can stand that boredom? Good games should hate your guts.