The introduction of Bernie Sanders’ Medicare for All bill on Wednesday — which would create a national health insurance program that covers everyone regardless of age, among other things — felt like the first positive step forward from congressional Democrats since Trump was elected. While the bill has no chance of passing until Democrats at least take back both chambers, the embrace by some in the party of Sanders’ plan is an acknowledgement that simply running against Trump’s record probably won’t be enough for Democrats to stop the Republican agenda — the party needs to propose and pass landmark legislation aimed at improving people’s lives.

Centrist pundits, however, were quick to pour water on the bare bones plan, sizing it up as if a plan put forward by a socialist senator to kill the private insurance industry and implement a massive new public program in its stead could ever have a chance of passing in the current Congress. In doing so, they miss the entire point of the political exercise, and show that they have learned nothing from the last couple of years.

First, it’s helpful to define what Sanders’ bill says and what it doesn’t say. It wouldn’t look much like the Medicare program as it currently exists; currently, Medicare is only available to those 65 years and older, and includes premiums, which for a majority of people are usually deducted from social security payments. Under Sanders’ bill, the first year would see the enrollment age expand to include everyone over 55 and under 18 , and the gap between the two ages would gradually be closed over the course of four years until everyone can enroll to receive government coverage, using a “universal Medicare” card to identify themselves and get claims processed.

It would provide basic coverage (primary care, hospital care, prescription drugs, and things of that nature) and expand it beyond that to include things like vision, dental, and “comprehensive reproductive” care — including abortions. Copays and deductibles would cease to exist; instead, your coverage would be financed by taxes. Sanders’ plan doesn’t have a funding mechanism, an obvious indicator that he knows it’s not ready for passage, but he did offer multiple options for paying for it: one based around raising taxes on the rich, another focused on raising taxes on Wall Street and “large, profitable corporation[s],” and lastly, one focused on buy-in from businesses and families. Under that option, monthly premiums would be capped at four percent for families; a family of four making $50,000 a year, according to Sanders’ estimates, would pay about $844 a year.

This isn’t a new idea. Every Democratic president since Roosevelt has at least explored the idea of government-run insurance for everyone, and in the House, Michigan Rep. John Conyers has introduced a Medicare for All bill in every session since 2003. What has changed is the support it has received publicly: a Kaiser Family Foundation poll taken in June found that public approval of a national single payer plan has jumped 14 points since the early 2000s, and Conyers’ bill in the House currently has 118 Democratic cosponsors eight months into this session, over 60 percent of the entire Democratic caucus. The last iteration of the bill died with just 62 cosponsors. (Sanders’ bill, by comparison, has 16 cosponsors so far, a little over a third of the Senate Democratic caucus.)

What has changed is the public support for Medicare for All.

On Sanders’ bill, New York magazine’s Jonathan Chait skeptically took the view that the historical barriers to single-payer health insurance — meaning that health care providers are paid exclusively by the government, which would be the case under Sanders’ plan — show why it just isn’t possible, and Sanders’ bill gets the U.S. “zero percent” closer to that goal. “Single payer has always been, and remains, a political dilemma that nobody has been able to resolve, and there is no evidence the resolution has grown any easier,” Chait wrote. “A single-payer plan would be nice, in a world that looks nothing like the one we inhabit.”

Let’s consider what the “world that we inhabit” looks like right now. Republicans control everything and are launching broad attacks on the safety net, civil rights, and the environment even as vulnerable parts of the country are getting pummeled by repeated natural disasters. Any Democratic bill that challenges Republican positions will get sent straight into the trash shortly after it’s filed, and Sanders’ proposal is no different: Trump has said that he’ll veto it if hell freezes over and it does pass through Congress.

But that’s not the most pressing thing right now, because the bill Sanders proposed is not meant to become law in its current form. It’s meant to be an argument for voting for progressive politicians. The long-term goal is to push a policy that will improve countless lives and is currently popular — a Kaiser Family Foundation poll from June found that 57 percent of Americans support expanding Medicare to include everyone — but the more pressing need is to drive turnout to take back the House and state legislatures from the right (and the center, where applicable), and hopefully get someone who is not Donald Trump elected in 2020 so these more long-term goals might one day become reality. The single-payer plan at the current moment is pure ambition, and that’s alright, because ambition is currently all we have.

Chait is right about one thing: it will be a challenge to convince those who already have decent employer-based insurance that this will be a good move for them, too. And critics might counter that this is not the first time there has been significant popular support for a national health insurance program: when Harry Truman announced his national health insurance proposal in 1945, a Gallup poll found that 59 percent of Americans supported it. After several years of repeated attacks by the American Medical Association aimed at convincing Americans that universal healthcare was a communist plot, support for Truman’s plan plummeted to 24 percent.

The bill Sanders proposed is not meant to become law in its current form.

The circumstances have obviously changed since the ‘50s – communism is no longer the bogeyman it once was, especially for millennials – but what this all proves is that there are fights to be won at the ballot box, in the streets, and over the dinner table. The course of history can be changed; it needs to be, if we’re serious about making a better future for ourselves and those who come after us.

While Chait worried about past failures, Politico’s Bill Scher asked why the left wasn’t happy with the system that we have. Why, Scher wondered, are progressives still talking about health care at all after Obamacare, and when other moral imperatives — such as the implementation of a humane immigration system, a massive push to combat climate change, ending the attack on voting rights, and dealing with problems of education, the opioid epidemic, and economic inequality (which is intrinsically tied to health care outcomes, but that’s besides the point) — are just as pressing?

These are all things, of course, that Sanders and most other single-payer advocates have been repeating for years. While a position on single payer is not a perfect indicator on how someone feels about other progressive domestic proposals, it’s a pretty good one. And electing the kind of people who would support Medicare for All — which is rapidly gaining popularity across the country as both Obamacare premiums increase and Republican alternatives continue to fall flat once people realize how bad they are — is a good way to make progress on other progressive policy goals, at least domestically. (When it comes to dismantling the American empire, as Emmett Rensin argued on this site last week, there’s little that politicians in our current system can do. We’re boned on that front until the revolution comes.)

What Scher conveniently ignores is that all of these things are also hard, particularly moreso at our current political moment because the party that’s in opposition to all of those things controls every branch of government. But that’s the job of the minority party, particularly one up against such an unpopular government: to distinguish themselves from the norm by pushing a multi-faceted agenda to create a country where conditions are better. That’s how you win, and apart from the moral reasons to protect targeted people, that’s why the left shouldn’t shy away from these fights, no matter how tough they are. If these things are necessary (and universal healthcare and everything that Scher mentions is), then they are worth the battles that will come with advocating for them.

This is the reason that every key progressive victory — labor rights, civil rights, women’s rights, LGBTQ rights — has been won over the past hundred years. All of these were pipe dreams at one point or another and aren’t anymore because fiercely determined activists decided that the status quo wasn’t good enough, and kept pushing all branches and levels of government until that dream became a reality. What really drives the kind of thinking that’s prevalent among Acela corridor pundits who started their journalism careers in the ‘90s appears to be the consensus that all of the radical change we could ever want has already happened, and that any victory won henceforth should be one won in pieces.

The job of a minority party is to distinguish themselves from the norm by pushing a multi-faceted agenda to create a country where conditions are better.

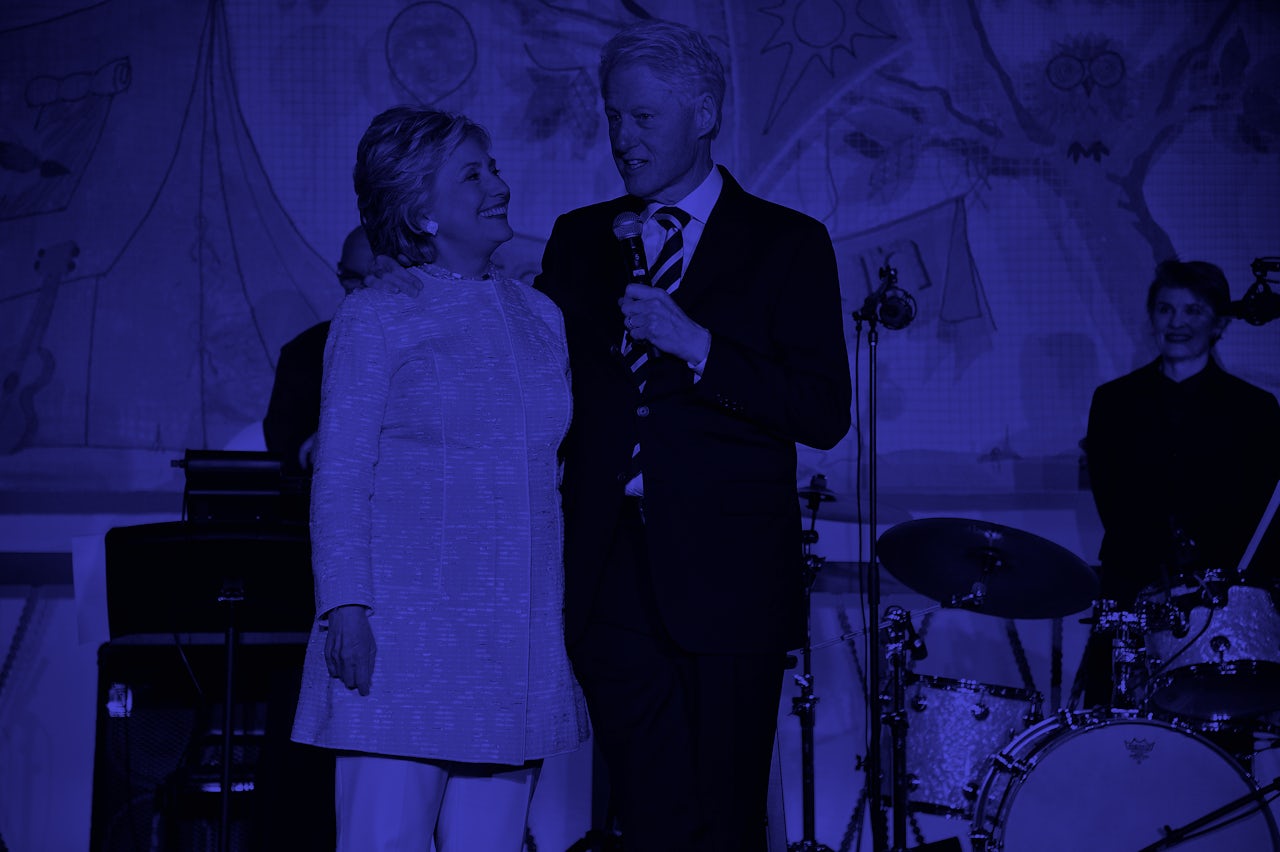

And this brings us to the current schism in Democratic politics. Both inside and outside of the Democratic Party, socialist and progressive political organizations that are openly antagonistic to the party leadership — Democratic Socialists of America, Our Revolution, and Justice Democrats, just to name a few — are gaining power and influence at the local, state, and national level. The center, meanwhile, has been dressed down by failure after failure both here and abroad. While former party standard-bearer Hillary Clinton grasps at relevancy by continuing to throw shots at him, Bernie Sanders remains the most popular politician in the country.

Former U.K. Prime Minister Tony Blair, for all of his many shortcomings, was at least honest when he said last February of the rise of populism on the left and the right: “I’m not sure I fully understand politics right now, which is an odd thing to say, having spent my life in it.” Centrist liberals would do well to concede the same, and consider that the center just doesn’t have the answers we need now. It never did.