Former President Barack Obama promised before leaving office that he would only speak out against Trump if his successor’s policies attacked America’s “core values.” On Tuesday, after Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced the end of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, an Obama-era policy that granted limited amnesty to young undocumented immigrants who met certain requirements, the former president was moved to issue a statement on Facebook. “To target these young people is wrong,” he wrote, “because they have done nothing wrong.”

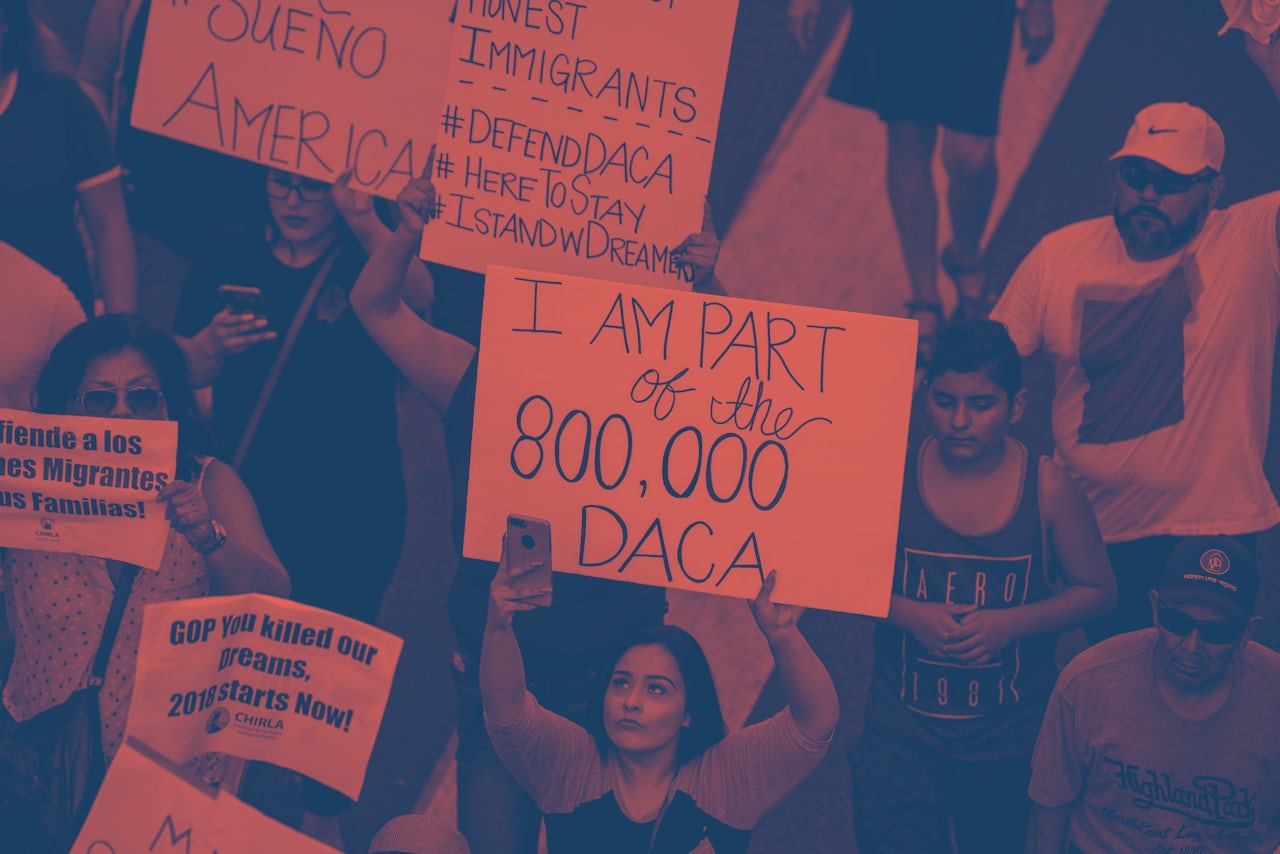

But Obama’s defense of DACA, as welcome as it may seem, reinforces an artificial dichotomy between the roughly 800,000 young DACA recipients and millions of others of undocumented immigrants.

As Obama noted in his recent statement, DACA recipients have to meet “rigorous” requirements: They must be younger than 36; need to have entered the U.S. before they were 16 years old, and have continuously lived here since 2007; must be able to prove they were here on June 15, 2012, when Obama announced the program; must currently be in school, or already have a high school diploma, a GED, or proof of military service; and must have a spotless criminal record.

Obama and others uphold these rigorous requirements as proof that DACA recipients are productive members of society who, unlike their parents, have “done nothing wrong.” After Sessions’ announcement, Republican Senator Jeff Flake expressed support for the program. “They should not be punished for the sins of their parents,” Flake said of the immigrants who have received amnesty under the program, echoing Obama’s rhetoric. But therein lies the problem: Even those who support amnesty for undocumented youth think of undocumented immigrants in general as sinners or criminals.

Those who speak out in support of DACA often cite the fact that young immigrants are hardworking, exceptional, and contribute to the economy. These qualifiers may have seemed necessary when the DREAM Act, which would have provided a path to citizenship for undocumented youth, was first introduced in 2001. But it didn’t work. The DREAM Act died in the Democrat-controlled Senate in 2010 after five Democrats voted against it. After the failure of the DREAM Act, DACA became the stopgap solution for young undocumented immigrants, which is why they are still referred to as DREAMers.

Obama used the same exceptionalist claims in 2012 when he implemented DACA via executive order. Unlike the DREAM Act, DACA lets young undocumented immigrants legally live and work in the U.S. but doesn’t provide an eventual path for legalization. By arguing that DACA recipients have earned their place in America, Democrats and others imply that most undocumented immigrants have not.

“President Obama and other folks who have come out in support have really been promoting the ‘good immigrant’ versus ‘bad immigrant [dichotomy],’” Janet Perez, an organizer with the immigrant advocacy group New York State Youth Leadership Council told The Outline. “We should be seen as humans wanting to survive. We just want to have basic things, to be able to work, to be able to live without that anxiety, without being separated from our families.”

By arguing that DACA recipients have earned their place in America, Democrats and others imply that most undocumented immigrants have not.

DACA distracted from Obama’s deportation of millions of other immigrants, a facet that eludes some of the program’s proponents. In a 2014 speech, Obama said his administration would target “felons, not families. Criminals, not children. Gang members, not a mom who’s working hard to provide hard for her kids.” By 2016, however, Obama had deported more than 2.5 million immigrants — more than any of his predecessors — causing some immigration groups to call him the “Deporter in Chief.”

Through DACA, Obama granted amnesty to nearly one million young undocumented immigrants — but he also paved the way for Trump’s attack on so-called “criminal aliens,” including many DACA recipients’ parents, by reinforcing the notion that the only undocumented immigrants who deserve to stay in the United States are those who were brought here as children and contribute to the economy.

Obama’s decision to target undocumented immigrants with criminal records may have seemed noble at the time, but it also gave the impression that a substantial number of immigrants are criminals, even though the data suggests otherwise. Trump took this idea further on the campaign trail, infamously calling undocumented Mexican immigrants “bad hombres” and claiming they’re bringing drugs and crime into the U.S. Since Trump took office, his administration has justified a surge in immigration arrests by claiming it’s getting criminals off the streets, although the Washington Post reported in April the majority of immigrants arrested under Trump either have no criminal record or have only committed minor crimes like driving without a license. Trump and his supporters also claim that most immigrants are a drain on social welfare programs, even though most don’t qualify for welfare. The president has also pushed legislation that would slash the number of legal immigrants admitted into the U.S. in half over the next decade. It’s clear that Trump’s war on immigrants will continue even if DACA survives.

It’s unclear what will happen to DACA now. Trump left the program’s fate up to a Republican-dominated Congress, which has six months to act before it ends. Some congressional Republicans said they’re willing to keep the program — but only if Democrats approve the budget for Trump’s border wall. If these Republicans have their way, a minority of undocumented immigrants — those who, as Obama wrote, “are here through no fault of their own, who pose no threat, who are not taking anything away from the rest of us” — can keep their amnesty, while the Trump administration continues to target the nearly 10 million undocumented immigrants who don’t qualify for the program.

Democrats expressed their disgust at the idea of trading DACA for border wall funding in August, when outlets first began reporting it as a possibility. “It is reprehensible to treat children as bargaining chips. America’s DREAMers are not negotiable,” Nancy Pelosi tweeted, using the term proponents of the DREAM Act have adopted to refer to undocumented youth. “Dreamers are not a bargaining chip for the border wall and inhumane deportation,” said Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer. Again, the lionization of DACA recipients has the side effect of demonizing their parents and other undocumented immigrants who don’t qualify for amnesty because they’re too old, didn’t graduate high school, or don’t have spotless records.

Now that a blatantly racist, xenophobic administration is in power, Democrats should be pushing for broad amnesty, not just for exceptional young achievers, but for all immigrants who have come to the U.S. fleeing violence and poverty. And they should do so by focusing on immigrants’ humanity instead of solely on their achievements.