President Donald Trump’s pardoning of Joe Arpaio provided yet another opportunity for Republican politicians to issue empty statements about how they disapprove of the president’s overt racism. Paul Ryan “does not agree” with the pardon, a spokesperson told CNN. John McCain condemned both the pardon and Arpaio’s long history of racially profiling Latinos. Despite their posturing, however, both Ryan and McCain supported racist voter suppression laws pioneered in Arizona and implemented across the country — laws that helped enable Arpaio’s long reign of terror.

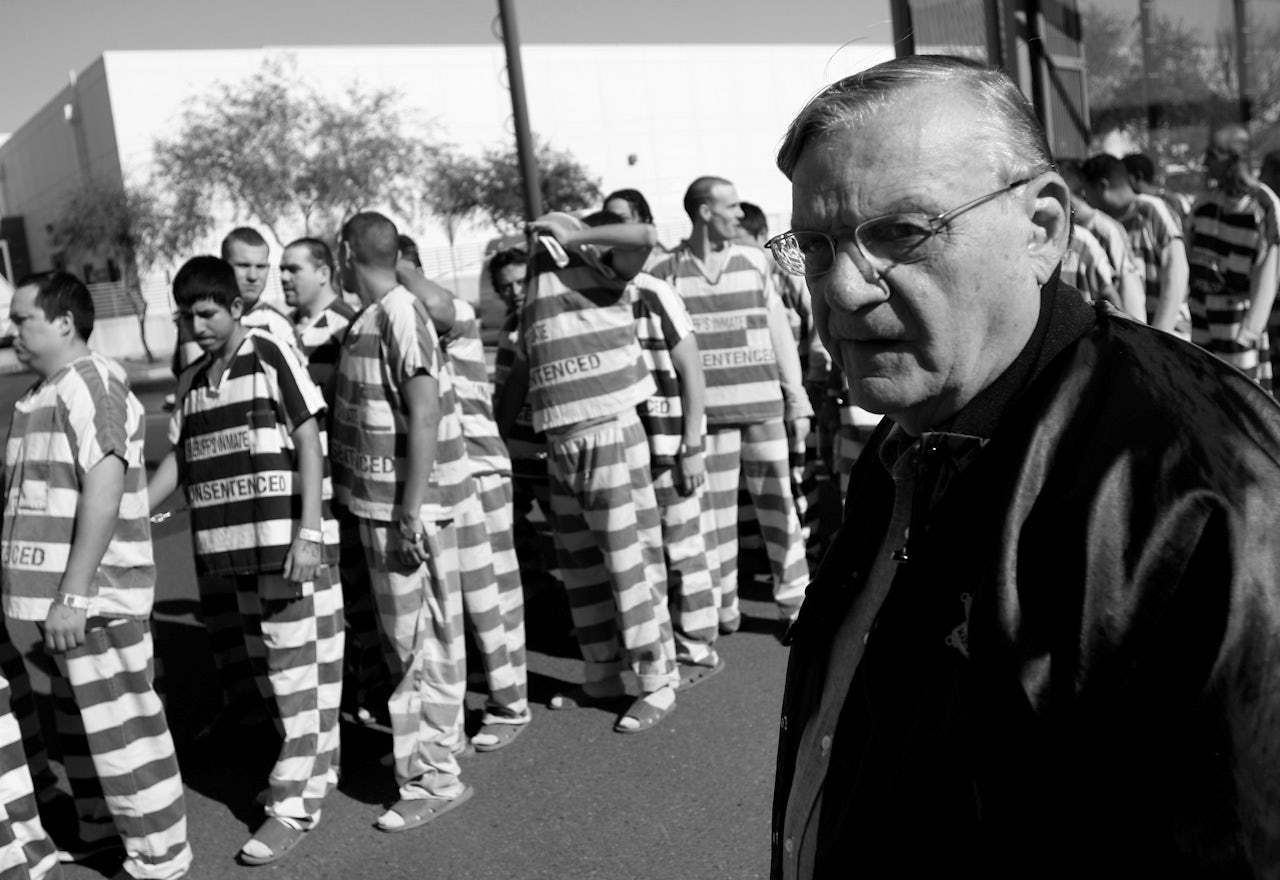

Unlike police chiefs, who are usually appointed by mayors, county sheriffs are elected officials and have no term limits. Arpaio was elected in 1992 on a platform of being tough on crime while saving taxpayer money. From the beginning of his time in office, Arpaio reveled in controversy and reports of his own cruelty. He regularly invited reporters to his infamous “tent city” jails, where inmates were forced to work in chain gangs, eat expired food, and sleep outside in the sweltering Arizona heat. His 1996 re-election bid was uncontested, and in 1997 his approval rating soared to 85 percent. In 2000, he was re-elected in a landslide victory with 66.5 percent of the vote, according to figures from the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office, possibly bolstered in part by an alleged bomb assassination plot the previous year. “If they think they are going to scare me away with bombs and everything else, it's not going to bother me,” Arpaio, playing his part as “America’s Toughest Sheriff,” proudly told television cameras.

Soon after, Arpaio’s reputation began to tarnish. An investigation revealed that sheriff’s deputies had staged the murder plot, and the ensuing lawsuit cost taxpayers more than $1 million. Arpaio was re-elected in 2004 regardless, but his support began to wane. He won just 56.7 percent of the vote in 2004, a dip that correlated with more people casting ballots. Between 2000 and 2004, the number of voters increased 31.7 percent in Maricopa County while support for Arpaio dropped by nearly 10 points.

Then came Proposition 200, one of the first voter ID laws in the country. Proposition 200, passed by state voters in 2004, required prospective voters to provide proof of citizenship when registering to vote and before casting a ballot. The law’s proponents claimed it was necessary to combat rampant voter fraud by immigrants, even though there was no proof that the alleged fraud was happening. Its opponents said it prevented voter outreach organizations from registering immigrant voters and stopped some citizens who were immigrants, low-income, or Native Americans from voting because those groups are more likely to be registering for the first time and less likely to have access to passports, original birth certificates, or naturalization forms. More than 10,000 Maricopa County residents’ voter registration applications were rejected the year after Proposition 200 went into effect, the Los Angeles Times reported. The law disproportionately affected native and Latino voters, according to reports by Colorlines and the New York Times.

McCain, who attempted to court Latino voters with promises of “comprehensive immigration reform” during the 2008 presidential election, parroted his party’s claim that immigrants were casting fraudulent ballots. That year, county election officials sent out English-language voting literature printed with the correct date of the election, November 6, but sent out Spanish-language literature printed with the wrong date, November 8, prompting questions about vote suppression.

Meanwhile, approval ratings and voter turnout over the years suggest that Arpaio’s popularity was dropping steadily, possibly due to his racial profiling of Latinos; his office’s mishandling and, occasionally, outright ignoring of sexual assault cases; his abuse of prisoners; his habit of arresting journalists and ordering raids on critics; and the fact that the many lawsuits filed against him cost Arizona taxpayers more than $147 million, according to one estimate. As Arpaio gained notoriety for his cruelty, Maricopa County residents became more emboldened in their fight against him. In 2007, after Arpaio partnered with business owners to harass day laborers, protesters gathered outside the businesses for weeks. Five years later, thousands of people protested outside Arpaio’s tent city jail.

By 2012, just half of Maricopa County residents approved of Arpaio, Rolling Stone reported. Still, he won reelection yet again, bolstered by Arizona’s racist voting laws and by the millions of dollars prominent conservatives from across the country donated to his re-election efforts, according to Rolling Stone.

The Supreme Court challenged Arizona’s restrictive voting laws in 2013, declaring that voters who were registering for federal elections couldn’t be asked to provide proof of citizenship. Arizona legislators complied with the court’s order by introducing more convoluted legislation: They implemented a two-tiered registration system that required people to provide proof of citizenship if they were registering with local ballots. The overwhelming majority of Arizona voters — 95 percent — register to vote with state forms, meaning the Supreme Court’s attempts at fixing Arizona’s broken voting system did not reach most voters.

Voter ID laws are typically attempts to restrict voting in low-income communities and communities of color. A 2013 University of Massachusetts, Boston study, for example, found that restrictive voting laws were introduced in areas where minority and low-income voters turned out in higher numbers. “The more that minorities and lower-income individuals in a state voted, the more likely such restrictions were to be proposed,” the researchers wrote. Proposition 200 wasn’t effective in curbing voter fraud, because the fraud wasn’t happening in the first place. ThinkProgress reported in 2013 that just 0.002 percent of non-citizens in Arizona were charged with voter fraud in the first eight years since Proposition 200 was implemented.

The racist voter suppression system pioneered in Arizona has since spread across the country

In addition to voter ID requirements, other developments have made it harder for Arizona residents to vote. The Supreme Court gutted parts of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, rolling back a requirement that states with a history of voter suppression — including Arizona — vet proposed voting law changes with the federal government. Following the decision, Maricopa County reduced its number of polling locations by 70 percent, from 200 to 60, and voters, especially those in Latino districts, found themselves waiting in lines for hours to cast ballots.

Arpaio was ousted in 2016 despite these ongoing attempts at voter suppression. His opponent, Paul Penzone, ran as a Democrat and won 56.3 percent of the vote. Even though there was record Latino turnout in Arizona that year, the Arizona Capitol Times reported that it was Republicans, not Latinos, who voted Arpaio out. Though Latinos turned out in record numbers for the 2016 presidential election, the effects of voter suppression are still palpable. A spokesperson for the Maricopa County Recorder’s Office told The Outline that there are approximately one million eligible voters in the county who haven’t registered to vote, and an investigation by the County Recorder found that as many as 58,000 people were denied the right to vote in the 2016 election.

The racist voter suppression system pioneered in Arizona has since spread across the country. Twenty states have passed restrictive voting laws since 2010, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. Trump, who won the presidential election but lost the popular vote, is using the voter fraud myth to champion even more restrictive voter laws — and Republicans are happy to play along. Ryan recently told MSNBC that he thinks Trump’s investigation into nonexistent voter fraud is “fine,” and that “we passed photo ID in Wisconsin because of our concern with this a few years ago.” Because of the law Ryan was referring to, Wisconsin Republicans were accused of voter suppression in 2016, and although Ryan later said he supported a voting rights bill, he ultimately refused to act on it. McCain and Ryan may have limply opposed Trump’s pardon of Arpaio, but they’re perfectly fine with the racist voting laws that helped keep him in power in the first place.

Voter suppression wasn’t the only thing that kept Arpaio in power, and these laws were implemented all over the state, not just in Maricopa County. But they undoubtedly played a part in keeping him in place — and they may help future Arpaios rise again.