Despite the fact that we’ve been at war in Afghanistan for nearly 16 years, Donald Trump said in a speech on Monday night that the military should extend the war and increase troop numbers in order to train the Afghan military and do counterterrorism operations. Trump also wants to give the military more authority to act unilaterally in Afghanistan, which should bother anyone who’s concerned with unelected officials making decisions on behalf of the U.S. government.

Trump’s latest move just further underscores the turn towards neoconservatism that he’s taking in his approach to foreign policy. As loud assholes like chief strategist Steve Bannon, short-lived communications director Anthony Scaramucci, and former national security advisor Michael Flynn leave the White House, they’re being replaced by people like chief of staff John Kelly and national security advisor H.R. McMaster – officials deemed respectable by Congress, the bureaucracy, and the media because they promise to continue a broken status quo.

McMaster is a particularly telling case. A lieutenant general in the Army who once wrote a book about how military leadership in Vietnam failed by not vocalizing its disagreements with Lyndon B. Johnson, McMaster’s February appointment as national security advisor to replace Flynn was well-received by the Washington foreign policy apparatus; Sen. John McCain called him an “outstanding choice,” and Rep. Adam Schiff, the top Democrat on the House Intelligence committee, said he was “happy” with Trump’s pick.

In his first six months on the job, McMaster (along with Kelly, who came on as chief of staff last month) has started clearing out the far-right cranks that populated the administration. One was National Security Council staffer Rich Higgins, who alleged in a memo that “Islamists” and “cultural Marxists” were collaborating to destroy America; The Atlantic reported that McMaster’s deputy fired Higgins after the memo was leaked. In turn, McMaster himself has been relentlessly attacked by Breitbart, the premier trade journal for white nationalism where Bannon has been executive chairman before and after his stint in the White House.

Trump’s reasons for approving the surge read like a set of second-term Bush administration talking points.

But having enemies on the right does not mean McMaster, who was a proponent of the Iraq War surge of 2007 and 2008, will do good things. As reporting dating back to May has revealed, he spearheaded the effort to push Trump towards committing more troops to the war in Afghanistan. Some of the more nationalist figures in the administration allegedly even took to calling it “McMaster’s War.”

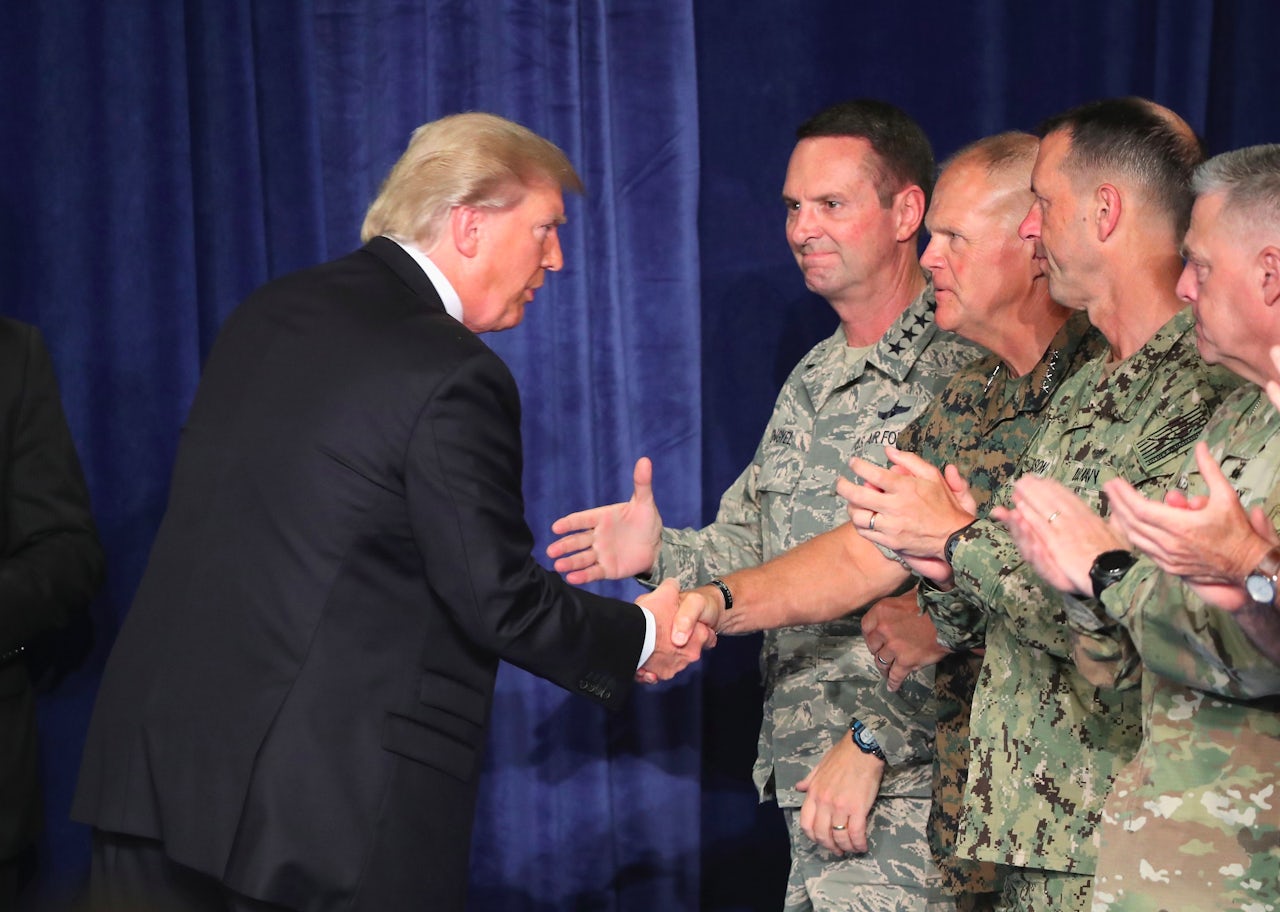

Trump’s capitulation on Afghanistan was a win for McMaster and a stunning turn for the president, who waffled constantly on what to do with the war but usually settled somewhere between advocating for an immediate withdrawal and staying put where we are. “But all of my life,” he said Monday night in a prime-time address, “I heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office.”

Trump’s reasons for approving the surge read like a set of second-term Bush administration talking points: that we need to be able to claim victory on something we’ve spent this much time on (we won’t), that the outcome if we leave would be “predictable and unacceptable” (like the outcome of staying there isn’t also both of those things), and that pulling out threatens national security — as if continuing our never ending quest to make parts of the Muslim world an unlivable nightmare for the people who live there doesn’t also threaten the lives of people here in the United States.

This brings Trump even more neatly in line with the foreign policy consensus that has ruled Washington for decades. The speech seems to have won over the people it was supposed to: in a town hall event on CNN, Paul Ryan agreed with the lack of a timetable for withdrawal, something Republicans often criticized the last administration for when Barack Obama attempted to slowly draw back from Iraq. “If [the Taliban] believe if we have an end date, some timetable, they will wait us out,” Ryan said. In addition, some Democrats like New Hampshire Senator Jeanne Shaheen supported the move, saying a timetable for withdrawal doesn’t “make sense.”

Trump's Afghanistan speech seems to have won over the people it was supposed to.

A roadblock to that plan is that the Taliban live in Afghanistan, so they’re uniquely suited to “wait us out.” If there’s one thing that Afghans have proved throughout their history, it’s that they’re exceptionally capable of “waiting out” military adventures in their country. It’s a problem that’s stumped the Brits, the Soviets, and the past two presidents. There isn’t a single person, aside from maybe George W. Bush’s Iraq War architect Paul Wolfowitz, who’s less capable to fix this problem than Donald Trump.

It gets worse. While the Trump administration hasn’t announced the number of troops it’s sending to the country, Fox News reported it’ll be around 4,000. It should be obvious that sending 4,000 people to Afghanistan is probably not enough to ‘win’ a war we’ve been at for nearly 17 years, and that this is probably just the start of a bigger expansion. One classified strategy that was “approved by the [NSC’s] principals committee,” according to a May report by Bloomberg, would have included a massive surge of 50,000 soldiers.

Trump, however, doesn’t seem to be bothered by any of this. He doesn’t care about how sane his advisors are, or about stability in Afghanistan, or about the lives of Afghans who are stuck in the crosshairs of a ceaseless war between the Taliban and a government propped up by the United States.

What he does care about is looking strong and getting approval from the press, and one of the only things he’s learned on the job is that an easy way to do both of those things is to make pointless decisions that will get people killed, like his ill-advised approval of a January raid in Yemen and his decision to bomb Syria in April. For some gullible pundits, this trick worked yet again: Philip Rucker at the Washington Post called him a “new President Trump” for acknowledging his previous sin of not wanting enough war, the New York Times’ Maggie Haberman called it his “best speech as POTUS,” and Fox News’ Ed Henry called it a “leadership moment” for Trump.

As Trump rids his administration of the white nationalists, he’s replacing them with more “respectable” officials who want him to make the same decisions as his predecessors, whose actions helped delegitimize American government to the point where we put a horny old TV man in the White House. And so continues the war in Afghanistan, which — like its role in the decline of the British empire and the Soviet Union — will perhaps be something that historians look to, along with Trump himself, when they try to explain the fall of the American empire.