President Donald Trump’s proposed budget seeks to slash $54 billion from social services including programs like Medicaid and Meals on Wheels. As these resources dry up, crowdfunding websites will further entrench themselves as extra-governmental welfare providers in order to fill the gap. For a lucky few, these sites are a lifeline. For most people, they are worthless.

These platforms are already immensely popular: GoFundMe claims to have raised $3 billion with the help of 25 million donors since 2005, while YouCaring has provided $500 million to worthy people and causes in just six years. Almost half the money raised on crowdfunding websites goes to healthcare-based causes.

We all remember crowdfunding’s heartwarming successes: the Brownsville, Brooklyn school that raised more than $1 million in scholarship money for its eighth-grade students in less than a month, or the fundraiser that provided nearly 13 Syrian refugee families with nearly $60,000 each.

But crowdfunding’s fatal flaw is that not every campaign ends up getting the money it needs. A recent study published in the journal Social Science & Medicine found that more than 90 percent of GoFundMe campaigns never meet their goal. For every crowdfunding success story, there are hundreds of failures.

For every crowdfunding success story, there are hundreds of failures.

Comic artist and writer Ted Closson wrote about his friend Shane, who died of diabetes-related complications in March. Shane set up a GoFundMe campaign to help him pay for insulin while waiting for his insurance to kick in. “He was $50 shy of his goal for over two weeks,” Closson said. “Shane died in horrible pain.” The Outline reached out to Twitter user Donald A. Sullivan, who tweeted at GoFundMe asking for help after two failed campaigns to help his wife and daughter with acute medical issues. “I started using it about seven months ago and still don't have any donations,” he said. “So I updated it a few days ago to see if anything will happen...." As of this writing, he had no donations on his $30,000 goal. He says he also started one for his brother. “He can't work for about 12 weeks and needs help with finances. We will see if it works. So far no luck.”

“As many happy stories as there are in charitable crowdfunding, there are a lot of really worthy causes when you browse these platforms that nobody has given a cent to,” Rob Gleasure, professor at the Cork University Business School, University College Cork told The Outline. “People haven’t come across them.”

And yet, fundraisers for individuals typically attract more donors than online fundraisers for established nonprofits and charities that could distribute money more equitably, according to a study of the crowdfunding website Razoo published by Gleasure and Joseph Feller, also a business professor at Cork.

“When you’re giving to a person, it’s because it feels good to give to them,” Gleasure told The Outline. “A specific target isn’t what it’s about; it’s the interaction rather than the outcome. They seem like someone who deserves it, you feel a little bit better about yourself for helping someone out.”

@gofundme Help for Holly and Wife. I tried your site 2× and got $0. Holly, beginning of renal kidney failure. Wife needs major Dental work

— Donald A Sullivan (@medon033) May 10, 2017

Once a nonprofit reaches its fundraising goal, they found, the money stops coming in — but donors will continue to flood individual recipients with donations long after their fundraising target has been met.

Feller and Gleasure’s report highlighted how fickle crowdfunding can be. Of all the Razoo campaigns started in 2013, they found, more than a third didn’t receive any funding at all. According to their report, donors are more likely to give to campaigns that feature lots of pictures and accompanying text.

Crowdfunding is as much about marketing as it is about charity, and those who can’t package their struggles in a compelling way — because they lack the social capital, the social network, or whatever magic ingredient causes some campaigns to go viral — often fade into obscurity.

Their report also mentioned the San Francisco-based microlending platform Kiva, which provides low-interest loans to entrepreneurs in developing countries. Several studies have suggested that donors on Kiva and similar sites prefer giving to women borrowers and to industries like manufacturing or education. Like on charitable fundraising sites, donors determine which people are worthy of their largesse.

“I started using it about seven months ago and still don't have any donations.”

Anyone can fight poverty from the comfort of their home by giving money directly to those who need it, New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristof wrote in a 2007, in a column reflecting the neoliberal ambition to fix the world without the messiness of government programs designed to benefit the collective. For donors, the appeal of crowdfunding lies in weighing the value of each potential recipient in a way government spending doesn’t allow for. You may not be able to choose which family pays their medical bills with your tax dollars, but you can choose which GoFundMe or Kiva campaign to support.

Two years after Kristof’s column, a debate erupted after a research fellow at the Center for Global Development, publicized an inconvenient truth about Kiva: Borrowers’ loans are disbursed before their stories are published on the website.

In other words, borrowers featured on Kiva aren’t waiting for their loans to be crowdfunded. Most of them already received loans from local microfinance institutions, and through Kiva, anyone can buy off this debt. This model makes more sense, even if it lacks the emotional affect of giving directly to a woman entrepreneur in a developing country. Microfinance critic Hugh Sinclair in a 2014 blog post called this a “deception,” writing that lenders are duped into thinking they’re giving a peer-to-peer loan, but actually have no say in whether their money goes to “entrepreneurs engaged in coca production or cock-fighting.” In other words, wealth redistribution is only deemed acceptable when those whose wealth is being redistributed handpick who gets the money.

Kiva began offering low-interest loans to U.S.-based small businesses in 2015, an endeavor co-founder Premal Shah said was spurred by the difficulty business owners faced when trying to take out loans after the 2008 financial crisis. Despite the notion that the Great Recession is over, working class Americans’ material conditions have hardly improved, and the rate of public spending has slowed — thus, the rise of crowdfunding. The post-recession recovery was sluggish, and real wages for U.S. workers barely budged — in fact, wealth inequality has widened along racial and ethnic lines since 2008, according to a 2014 report by the Pew Research Center.

There’s a positive correlation between austerity and crowdfunding, according to the Social Science & Medicine report. In states where access to public insurance is limited, people are more likely to turn to online fundraising to pay their bills — and the most successful fundraisers are those that created narratives “about illness, need, deservingness, hope, and suffering.” If you want people to give to your campaign, you first need to prove that you’re deserving of the money. Nora Kenworthy, one of report’s co-authors, called the phenomenon an “archive of suffering.”

“People say, ‘I wish I didn’t have to do this. I’m so embarrassed,’” co-author Lauren Berliner said in a story for the University of Washington’s Simpson Center for the Humanities. “They use disclaimers: ‘I wouldn’t do this unless I had nowhere else to turn.’”

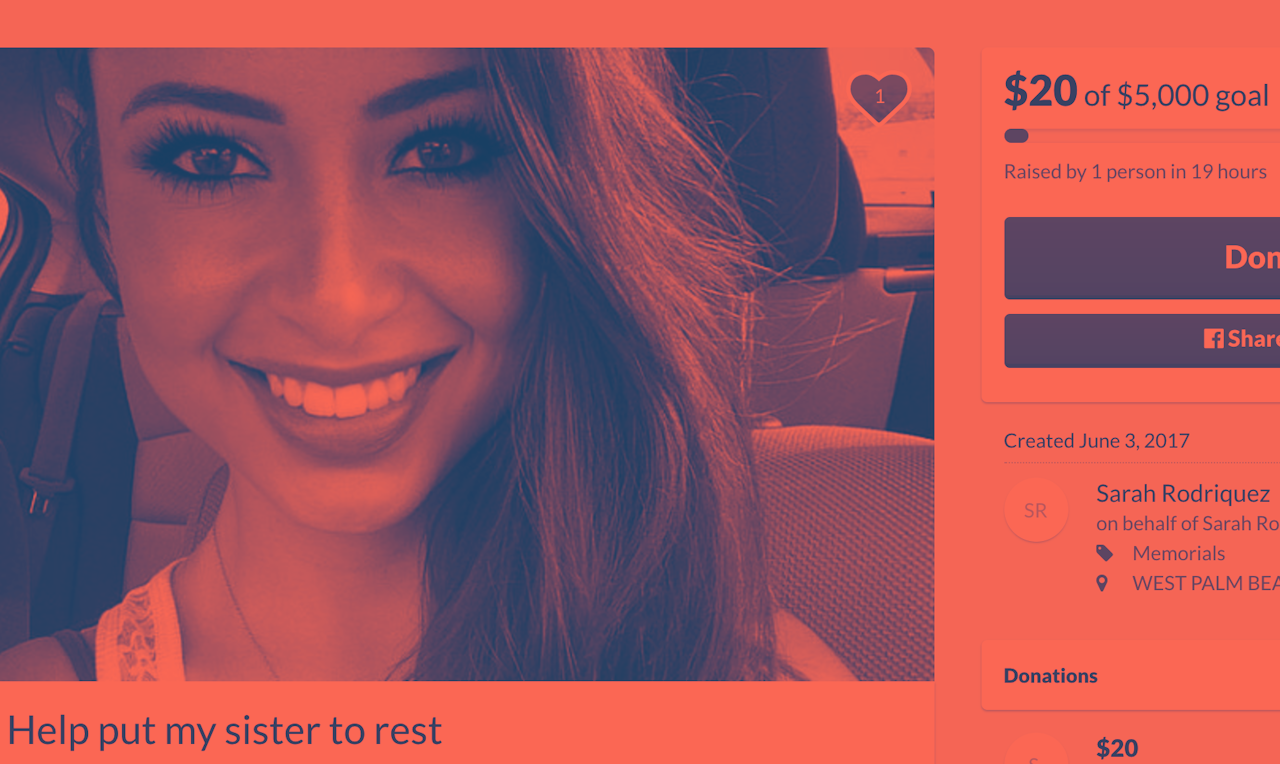

Berliner and Kenworthy highlighted two contrasting GoFundMe campaigns. One, by “Team SuperVan,” has raised more than $13,000 for Van, a six-year-old boy with a rare form of tissue cancer. Another, titled “Family in Need,” netted just $550 for a family that “has been struggling with our bills” due to surgeries, the autism diagnosis of two sons, the risk of home foreclosure.

“‘Family in Need’ seems to have needs without end, beyond medical costs. A donor might ask why it would be worth it to help them,” Berliner said.

Donors are more likely to give to campaigns that feature lots of pictures and accompanying text

Fundraisers for medical expenses, scholarship funds, and past-due bills are framed as individual stories rather than as the result of “structural conditions of austerity,” shifting the blame from institutions that fail to support people in need to the individual who fails to market their story in a way that resonates with donors, they argued.

Trump’s proposed budget would widen the wealth gap even further. One of the many programs he seeks to eliminate is the Appalachian Regional Commission, an agency set up in 1965 to “address the persistent poverty and growing economic despair” of the region, which has improved little in half a century. And despite the fact that Trump is cutting this and other necessary programs to increase defense spending, that doesn’t apply to all military spending across the board: He wants to cut disability benefits for veterans, too.

It’s unlikely that every line item in Trump’s budget will be approved, but many will, and millions of people will suffer as a result — some will probably turn to crowdfunding to pay for services once provided by the government. There are many ways in which crowdfunding is a poor substitute for social services, but the main issue is this: Crowdfunding doesn’t help everyone. In fact, it doesn’t help most people.