It is difficult not to view Donald Trump’s administration, regardless of its politics, as combative towards at least some portion of the American public. Unlike previous presidents who ultimately relied on messages that conveyed some attempt — real or theatrical — at national unity, Trump’s team has decided to draw very clear lines between his supporters and everyone else. Whether it is the press, “radical Islam,” or the “politically correct,” Trump’s style of leadership appears to rely on scapegoats. This bitter political ideology will likely be ineffective in guiding the country through the next decade of developments in the economy.

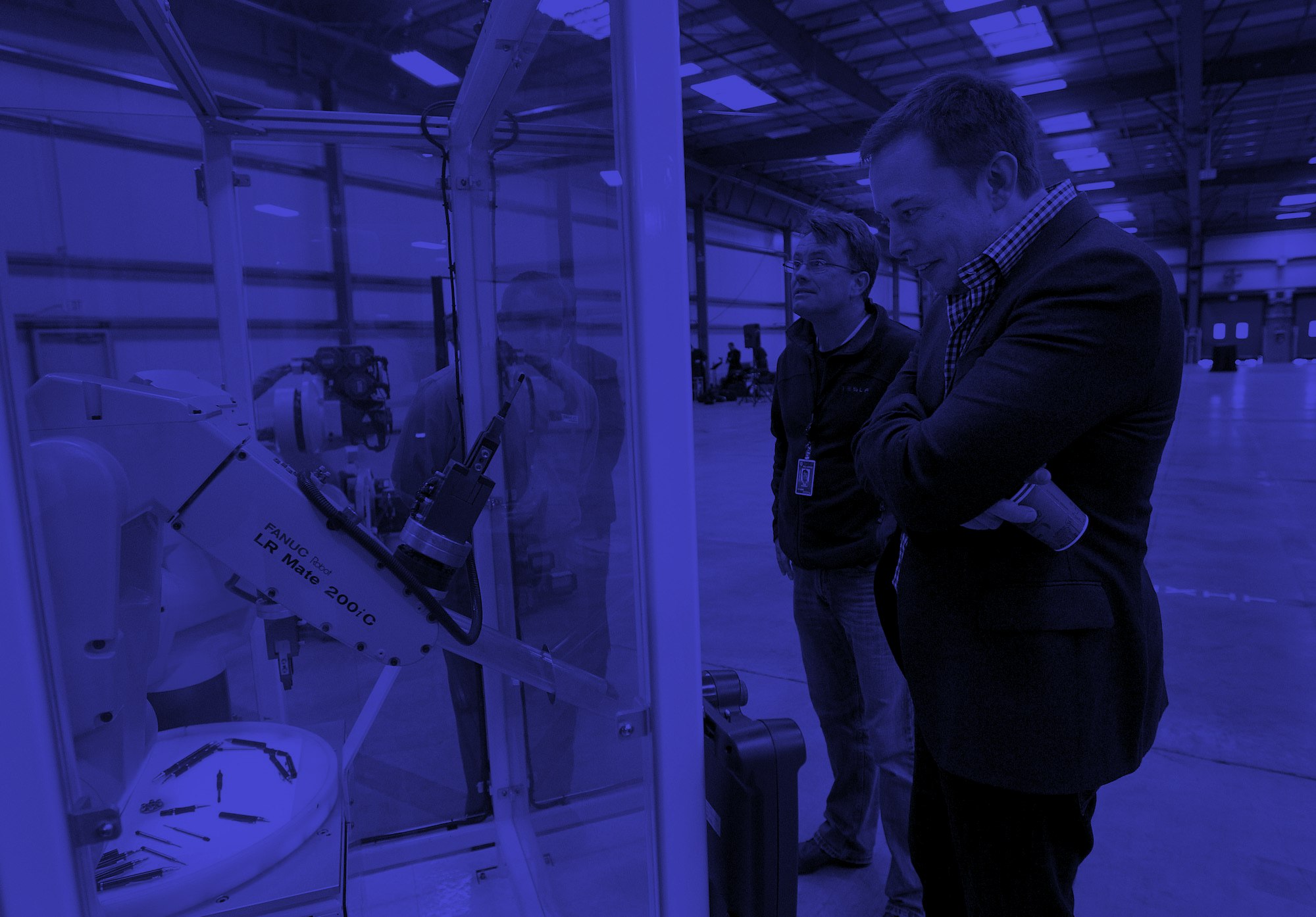

As artificial intelligence, robotics, and new forms of automation continue to flourish, the forms of work that millions of Americans rely on are at risk. The political solutions to navigating these changes are going to require broad public initiatives that haven’t been accomplished in decades, and everyone is going to have to be on board.

Before leaving the White House, President Obama commissioned a report titled Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and The Economy, that provides an in-depth look at the changes that will occur as automation becomes more sophisticated. Far from the doom and gloom projections of a workplace without humans, the report charts the subtle ways that, at scale, AI will have a tremendous impact on how our economy, and labor force, functions. Citing the current wave of AI, which the report describes as having begun around 2010, the study describes how the the types of jobs available in the economy are rapidly changing, and these changes are primarily impacting low income and less educated Americans.

According to the MIT Technology Review, 83 percent of jobs that pay less than $20 an hour are under threat from automation. Simply put, as technology makes things like ordering a cheeseburger, buying groceries, and shipping goods, require fewer human beings involved, the number of jobs available for poor Americans will shrink dramatically.

Ford, a company whose name is synonymous with the dream of American manufacturing jobs, recently announced goals to provide fully autonomous ridesharing by 2021, and earlier this month, allocated $1 billion for the autonomous vehicle startup Argo. Trump’s former candidate for Labor Secretary, Andrew Puzder, wrote in the Wall Street Journal that, in areas like retail and foodservice, increases in minimum wage were to blame for the increase in automation. Of course, he also cites consumer preference as “The major reason.”

Lots of high-minded technological thinkers, particularly Elon Musk, have proposed a universal basic income, a form of wealth distribution that ensures every citizen receives a baseline income whether or not they are employed, as a likely solution to the problem of workforce automation. But the White House report takes a more somber approach, describing a basic income as “giving up on the possibility of workers’ remaining employed.” Instead, the report suggests a number of policy proposals (like Obama’s national free community college initiative, and expanded unemployment benefits) as ways of actively facilitating the transition into a more AI driven economy.

In an interview with the MIT Technology Review, Mark Muro, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution calls for what he calls a “universal basic adjustment benefit.” Unlike a universal basic income, it would involve targeted benefits for those left out of the workforce, providing tools like wage insurance, job counseling, relocation subsidies, and other financial and career help.

The White House report points out that the U.S. government spends roughly 0.1 percent of its GDP on programs to help people deal with changes in the workplace — much less than similar developed nations. This funding has also declined over the past three decades.

This is where Trump’s style of leadership appears, at worst, disastrously cynical, and at best, ignorantly short sighted. By invoking a bygone era of American manufacturing, Trump undoubtedly tapped into a significant form of anxiety present in a large portion of the country. But his solutions, a dramatic reduction in immigration and tax breaks for corporations who move sparse manufacturing jobs to the U.S., don’t even take into account changes in technology.

This is where Trump’s style of leadership appears, at worst, disastrously cynical.

The people left behind by the advances in automation have faced the steady creep of obsolescence, in the form of a shrinking number of available jobs, for the past decade, and Trump promised to rewind time, to a period before artificial intelligence. A post-election analysis from FiveThirtyEight found that one of the best predictors of whether or not a county voted for Trump wasn’t unemployment or income, but its proportion of jobs that are considered “routine,” an economic term for jobs that are easily automated. Areas with a high percentage of routine jobs voted in significant numbers for Donald Trump’s vision of an America stopped in time.

Republicans in the House and Senate, similarly, have no discernible plan for how to address technology’s impact on the workforce. They’ve instead spent the past decade working single-mindedly on taking control of the government in order to enact an economic and moralistic vision frozen in the 1980s.

“I’m very worried that the next wave [of AI and automation] will hit and we won’t have the supports in place,” Lawrence Katz, an economist at Harvard told the MIT Technology Review. Katz’s research is focused on how public spending on education in the 1900s helped America make the economic shift from agriculture to manufacturing. There’s plenty of reason to believe that, as Wired’s Clive Thompson points out, the next blue collar job in America could be computer programming. An initiative to teach coding to the millions of Americans whose jobs will slowly phase out in the face of AI would take years to develop and enact, and it doesn’t even appear to be on anyone’s mind.

The report from the final days of Obama’s White House makes sure to point out that:

Historically and across countries, there has been a strong relationship between productivity and wages—and with more AI the most plausible outcome will be a combination of higher wages and more opportunities for leisure for a wide range of workers. But the degree that this materializes depends not just on the nature of technological change but importantly on the policy and institutional choices that are made about how to prepare workers for AI and to handle its impacts on the labor market.

The next few years will find our government squabbling over a health care law that for the most part works, and passing dramatic forms of austerity that have never proven effective in the long term. The cost of attending college, a critical tool for finding a job in the new economy, will likely continue to rise unabated. All the while technology will continue to alter the way millions of Americans work, for better and for worse.