Several weeks ago, an acquaintance forwarded me an email in which attendees of the Women’s March on Washington — slated to occur this Saturday in protest of the inauguration of Donald Trump — and other protesters were cautioned against filling out any surveys they might receive from event organizers. The author, a march participant, warned recipients to be especially wary of ones requesting details of location, personal identity, or planned route to the march. “If you are planning any protests of the inauguration, please be aware that you may be a target of [right-wing] operatives,” the email said. “There will be moles in your campaigns. PLEASE make sure to vet your volunteers.” Around the same time, an objectivist outlet called The Undercurrent and the group Americans Take Action led a counter-sting that exposed Allison Maass, an ally of James O’Keefe of the right-wing Project Veritas, attempting to induce Trump foes to engage in potentially criminal acts (e.g., inciting a riot, shutting down a bridge) at the inauguration.

Some would-be marchers have been intimidated by the ever-present threat of surveillance, as well as campaigns by right-wing operatives like Maass. A Turkish woman who left her home country in part to escape a repressive government told me she would love to attend the march, which is expected to draw hundreds of thousands of women, but she’s afraid. She has a green card, she said, “But I think they’ll be watching the people who show up, and I don’t want to be targeted by the administration if I go.”

Women activists have experienced this kind of thing before. Some of the first known targets of surveillance and infiltration were women fighting for the right to vote.

“They were most helpful”

Around 1908, when she was 20 years old, a German-born woman named Margaret Schencke left home after a bitter fight with her parents. She went to England and rechristened herself “Margot.”

Schencke was drawn to the suffragettes, as the militant followers of Emmeline Pankhurst, head of the Women’s Social and Political Union in England, were called. She began selling their newspapers on street corners shortly after arriving in England.

One day, in 1975, she came across an unidentified photograph of herself in The Sunday Times. The photo was taken at Holloway Prison in 1913.

Schencke wrote Midge Mackenzie, editor of Shoulder to Shoulder, a BBC television serial and book about the English suffrage movement, to tell her that she was the woman in the photo. (This letter was shared with me by Schencke’s grandson.)

Schencke told Mackenzie she had joined a suffragette march organized in response to Pankhurst’s 1913 arrest. “I decided then to make my personal protest by throwing a stone through a Home Office window,” she explained. “I discussed this with two women (sisters) I walked with but did not know. They were most helpful … They gave me a stone.”

Later it emerged that these “helpful” women were police informants who, once they had equipped Schencke with a stone, telephoned Scotland Yard to inform them she was about to commit a crime and ensure her arrest. Wishing to avoid being sent back to Germany, she gave her name as Margaret Scott and received a one-month sentence.

In a 2003 Guardian article on surveillance and the suffragettes, titled “Big Brother and the sisters,” Alan Travis described that year’s March of the Women exhibition at the National Archives in Kew, London. The exhibit featured files showing that in September 1913, “the Home Office had ordered that the photographs of all the suffragette prisoners be taken without their knowledge.”

In other words, the surveillance that is now commonplace in Britain and many other countries, including the United States, was pioneered as a means of circumventing the suffragettes’ refusal to have their photographs taken and deliberate attempts to “spoil” police photos by making faces, rendering the pictures useless as a means of identification.

Travis described one such photograph of Evelyn Manesta, a young protester from Manchester: “She has the arm of a prison warder around her throat to restrain her, and she is grimacing in an attempt to distort her face.” The photo of Manesta was ultimately used in a wanted poster, but the image was doctored to conceal the policeman’s arm around her neck.

Law-breakers

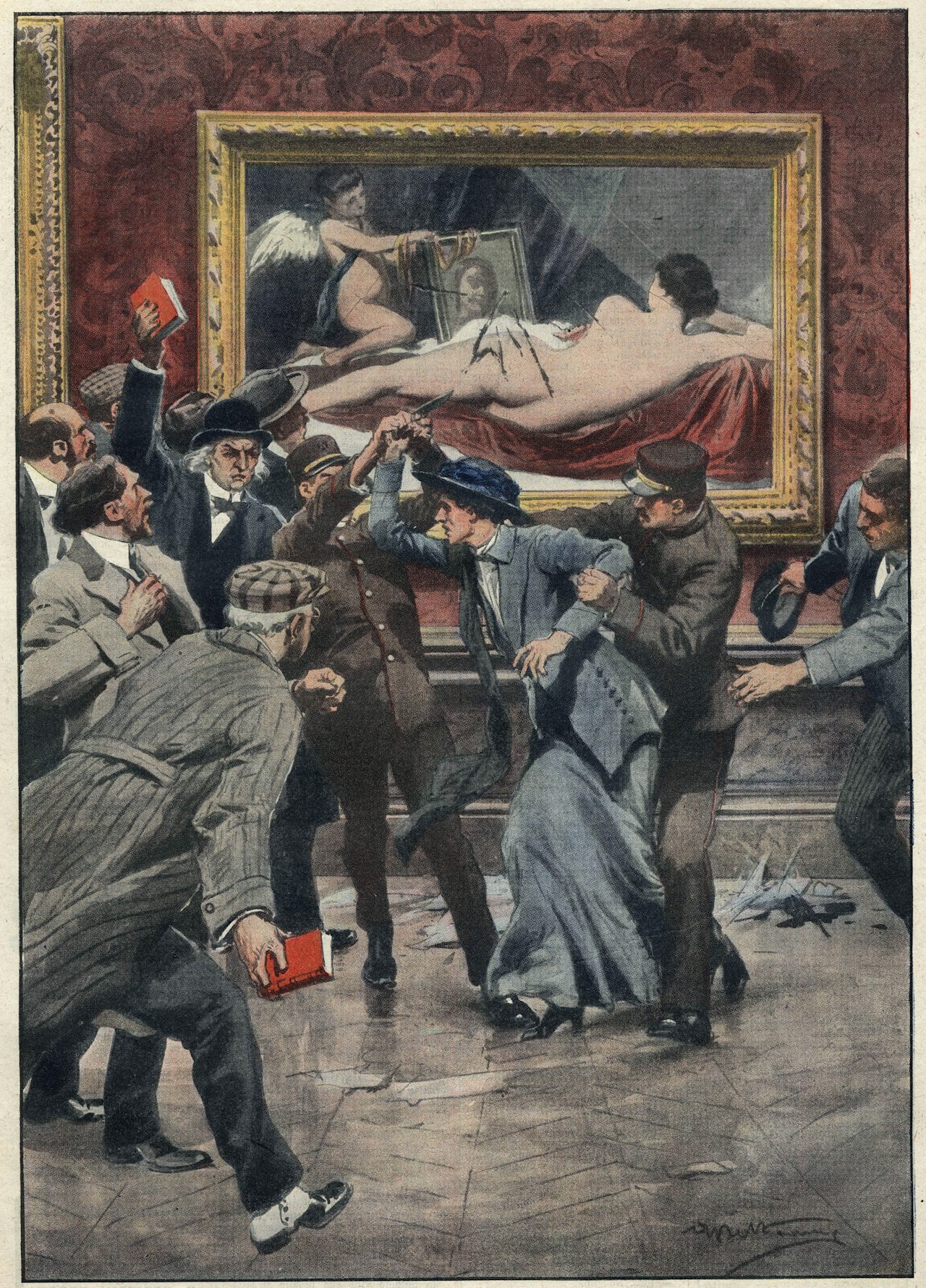

The suffragettes did more than march. In 1909, two were discovered to have plotted the assassination of the Liberal prime minister Herbert Asquith. In 1913, militants embarked on a campaign of arson, targeting residential homes, golf courses, and schools, and bombed a home of David Lloyd George, the Chancellor of the Exchequer. In 1914, Mary Richardson took a chopper to Diego Velázquez’s “Rokeby Venus” painting at the National Gallery in London.

In the United States in 1919, Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party protested President Woodrow Wilson’s “betrayal of American women” by burning him in effigy. An unsigned 1917 letter, which appeared on the letterhead of Raymond W. Pullman, major and superintendent of the DC police, and was addressed to American political scientist Louis Brownlow, complained of the “suffs” inciting riots so successfully that arrests had to be made and picketing halted “in order to prevent bloodshed and possible serious injuries both to the women and citizens.” Pullman, or whoever was writing on his stationery, claimed that the women had taken to “biting people” and “breaking banner staffs over heads of bystanders,” and that at least one had “armed herself with a 38caliber [sic] Colt and fifty rounds of amunition [sic].”

Their political beliefs were as threatening as their actions. When Emmeline Pankhurst applied for admission to the United States in 1913, a concerned citizen wrote a letter to President Wilson urging him to deny her request on the grounds that she was “one of the most monstrous women in the world,” had “poisoned the minds of thousands of families in England,” and intended to “revolutionize the homes of thousands of families” in the United States. Yet Pankhurst’s tactics were exceptional; in a 1912 letter to David Lloyd George, Millicent Fawcett, head of the larger and more moderate National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, dismissed radical members of the Women’s Social and Political Union as a “small section of law-breakers” for which “the great mass of law-abiding suffragists” should not be punished.

Voyeurism

There’s a whole new universe of personal data, including email, cell phone data, and social media accounts, that governments around the world can and do monitor, legally and not. Tools of surveillance have enormous potential for abuse, and there is evidence that they have been used to target women, who are uniquely vulnerable to intimidation, harassment, and stalking by abusive partners and privacy violations by bored or prurient strangers.

In 2011, a British immigration officer was fired for adding his wife’s name to a list of suspected terrorists to prevent her from returning to Britain after visiting relatives in Pakistan. Two years later, at least a dozen employees of the US National Security Agency were found to have used government surveillance tools to access the phone records or email of current or former spouses and lovers. According to a 1999 study of CCTV operators in Britain, “the thighs and cleavages of scantily clad women are an easy target for those male operators so motivated … 10 percent of all [surveillance initiated by someone outside the CCTV control room] on women and 15 percent of operator-initiated surveillance on women were for voyeuristic reasons.” Instances of surveillance being used to spy on women for the camera operator’s sexual gratification outnumbered instances of surveillance being used to protect women from crime by five to one. In North Belfast in 2014, a CCTV operator was convicted of voyeurism and misconduct in a public office for spying on a woman in her apartment in hopes of catching her nude.

Even women who are government officials, or “de facto” government officials, as a court deemed Hillary Clinton in 1993, have been subjected to government surveillance. Although the FBI never launched an official investigation of Eleanor Roosevelt, it managed to compile over 3,000 pages of reports on her activities, including letters filled with lurid descriptions of her suspected Communist leanings. The agency even bugged her hotel room and filed reports suggesting, fallaciously, that she was having an affair with her friend Joseph Lash. (President Franklin Roosevelt apparently disbelieved the reports and was angered by the surveillance.)

Bodies on the line

You don’t need a long-range camera to harass or intimidate a woman or intrude on her privacy. Women who display their bodies in public are often seen as fair game. “When they sold Votes for Women [the Women’s Social and Political Union newspaper] on street corners or chalked pavements,” wrote Martha Vicinus in Independent Women: Work and community for single women, 1850-1920, “women were horrified at men’s reaction. … Mary Richardson found that men came up to her ostensibly to buy a paper, but actually to whisper filthy language in her ear.” Vicinus also recounted treatment “far worse than dirty words”: The suffragettes “could be repeatedly pinched, punched in the breasts, fondled under their skirts, and spit at in the face, have their hats pulled off, have rotten fruit thrown at them, and suffer other indignities.”

Before the January 21 Women’s March, the only other large-scale, women-led protest pegged to a president’s inauguration was a massive parade for women’s suffrage led by Alice Paul and the National American Woman Suffrage Association on March 3, 1913, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. It was intended to call Wilson, who at that point opposed women’s suffrage, to account. By the standards of the time, it was huge, with between 5,000 and 8,000 marchers, nine bands, four mounted brigades, and 20 floats. Paul’s bid to attract crowds and national media coverage from those in town for Wilson’s inauguration paid off. “‘Where are all the people?” a member of Wilson’s staff reportedly asked upon arriving in Washington to disappointingly little fanfare. He was told they were watching the women march.

Although it succeeded in drawing media attention and crowds, the march soon turned ugly for participating women. Male spectators blocked the women’s path, threw lit cigarettes at them, made sexually aggressive remarks, grabbed their clothing, and tripped, spat at, and shoved them. Instead of protecting the women, the police joined in this treatment, jeering at marchers that they belonged at home. The suffragists’ male supporters were heckled and asked, “Where are your skirts?” At least 100 marchers had to be treated for injuries at a local hospital, and the chief of police had to ask the secretary of war to authorize a cavalry troop to help restore order.

Male authorities of the era often sympathized with violent male bystanders. The June 1914 edition of a British paper, The Morning Post, reported on the trial of several men accused of attacking suffragettes in Streatham Common: “A hostile crowd gathered, and there were ugly rushes to get at the women speakers. … There was an effort on the part of the young men … to put the militants in the pond.” The judge in the case, Lister Drummond, noted that it was “impossible to shut one’s eyes to the fact that the behaviour of these women had created a strong feeling of resentment and disgust.” So great was Drummond’s understanding of the men’s feelings that he found he was unable to impose any penalty for their actions.

The New York Times thought rough treatment by the police was also perfectly justifiable. In March 1919 the paper ran a story claiming that 200 militant suffragists had attacked “patrolmen and civilians with their banners and fingernails,” only to be “repulsed” by police, who, the paper of record assured readers, “treated them as patiently as possible under the circumstances.”

When incarcerated, suffragists in England and America led hunger strikes and were violently force-fed, sometimes up to three times a day. The authorities refused to dignify their cause by recognizing them as political prisoners — a privilege that had, in some instances, been extended to men guilty of similar crimes — treating them instead as a cross between lunatics and juvenile delinquents.

When incarcerated, suffragists in England and America led hunger strikes and were violently force-fed.

The suffragists’ horror at force-feeding was related for some to their previous work as members of the Ladies’ National Association for the Repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts, a group founded in 1869 to oppose a series of English laws designed to protect men from sexually transmitted diseases by authorizing the police to round up women they suspected of being prostitutes and confine them to hospitals indefinitely, where they were forced to submit to invasive gynecological exams performed by male doctors.

Ninety-five years later, black activist Fannie Lou Hamer and a group of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) volunteers were arrested for attempting to desegregate a Mississippi lunch counter. In jail, Hamer and two female colleagues received what Danielle McGuire described in At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance as “savage and sexually abusive” beatings at the hands of the local police, who called them “bitch” and vowed to teach them “how to say ‘yes, sir’ to a Mississippi white man.” Female civil rights activists in the South were raped, molested, made to strip naked and exposed to male prisoners, and subjected to unsanitary, unnecessary, and unwanted vaginal exams by jail attendants and prison guards, some of whom performed the exams using gloves dipped in Lysol.

“They feel safer being more brutal to women”

Contemporary activists like Jodie Evans, co-founder of Code Pink, a women-led human rights advocacy group that favors direct action, said she has encountered gentler treatment from the White House police than from the regular DC city police. This observation echoed Vicinus’s account of Black Friday, a November day in 1910 when a large group of suffragettes were attacked by policemen and bystanders when they attempted to reach the House of Commons. In the end, 115 women and 4 men were arrested. The police’s decision to use men from the East End rather than “A” division men, who were sympathetic to the suffragettes, prompted much of the violence, since the East End police “had no compunction about treating the suffragettes with brutality and sexual aggression.”

Even in 2017, drawing attention to oneself in public is still frowned upon, especially for women. “People try to get us to behave all the time,” said Evans. “They want us to be nicer and more polite… ‘Don’t you know that’s not effective? Don’t you know you’re behaving badly?’ And we hear that from men and women.”

“They want us to be nicer and more polite.”

Unarmed women also make easy targets. “The level of abuse and violence that people feel like they can get away with, with women — cops, people on the other side. … They feel safer being more brutal to women,” Evans said.

Dr. Anjhula Mya Singh Bais, co-founder of the Bais-Selvanathan Foundation, said that, while researching war suffering and trauma in Sri Lanka, she was “often targeted by the former Sri Lankan government, with threats and phones being tapped, etc.”

When asked if she thought her treatment was influenced by gender, she was emphatic: “Of course it’s influenced by gender, even if not said, thought, or planned directly. Rape is one of the biggest war tools out there, and that is the unspoken possibility and potentiality with all females.”

Bais, an Indian with an American passport who is married to a Sri Lankan, recalled sitting in a restaurant discussing Sri Lanka with some colleagues in 2013. About 10 feet away sat five men in their 50s she described as “government thugs and henchmen.” Suddenly one man slammed his fist on the table and said loudly, “Anjhula, I will not let you talk about Sri Lanka like this; you cannot.” Bais said she had no idea who they were, “and alarms were going off on in my head that they knew my name.”

For Bais in that moment, open defiance wasn’t worth the risk: “I folded my hand in acquiescence … bowed, said sorry and left. I have to be alive in order to make a difference.”

Women’s Marchers prepare for battle

Lena K. Gardner, a Minneapolis-based collaborative organizer working with Standing on the Side of Love and Black Lives of Unitarian Universalism (BLUU), a partner of the January 21 Women’s March, said she assumes she is always under surveillance. “I mean that in a realistic, not a paranoid way. We know from FOIA requests that the local sheriff [collects local cell phone data].” She said she also expects there may be agitators and undercover police attempting to incite violence at the march. “We want to empower people to handle that in a way that is de-escalating and in line with our nonviolent values,” Gardner said. “By joining the movement you will be targeted. … [Activists] are always criminalized as a means of being delegitimized. I fully expect this president and this administration to double down on that tactic.”

Neema Singh Guliani, a legislative counsel with the American Civil Liberties Union who focuses on surveillance, privacy, and national security issues, agreed.

“There’s a very real concern from activists and people who want to participate in marches, political rallies, etc., that they’re going to be surveilled by law enforcement,” she said. “Our history suggests this isn’t an idle fear.”

Guliani said what’s needed are better guidelines and stronger restrictions on the kind of data the government can collect and how that data can be used. People deserve to feel comfortable exercising their constitutional rights without being subjected to unwarranted surveillance, and “current laws and policies in most jurisdictions are not strong enough to prevent abuse.”

In 1913, during a speech in Hartford, Connecticut, Emmeline Pankhurst said that women, though capable of withstanding torture, possess a strength more moral than physical: “We are showing [male politicians] that government does not rest upon force at all: It rests upon consent.” A century later, her great-granddaughter, Helen Pankhurst, told The Huffington Post that “it’s become a lot easier” to be a feminist. “There’s no issue of force-feeding, there’s no issue of violence by the state for anything that I am demanding.”

To an extent, she is right: After bloody, ongoing struggles, many women in the UK and the United States lead freer lives than their great-grandmothers did. But as the women who founded Black Lives Matter in the United States and women in other countries around the world know, state violence is hardly a thing of the past.

On January 21, women and their allies will protest a US president who, during a debate, threatened to jail his general election opponent and has described news outlets that embarrass him as “failing pile[s] of garbage” that will “suffer the consequences.” Though arguably as resolute as their 1913 predecessors, this year’s marchers are no less vulnerable to violence and intimidation.