The bright pink Chanel skirt suit Jacqueline Kennedy wore that fateful day in Dallas when her husband, the then-president of the United States, was assassinated has become as iconic as the woman who wore it. In Pablo Larraín’s film Jackie, the first time we see the suit in all its glory, free from the distractions of people crowding around her or flashing cameras, it’s covered in blood. That Larraín and screenwriter Noah Oppenheim choose to show this suit most often when it’s soiled by blood wrestles it (and the woman wearing it) from being stoic iconography with no nuance or humanity to speak of. This choice also exemplifies the strongest aspect of Jackie — its use of horror techniques to create a subversive portrait of female identity in the wake of grief.

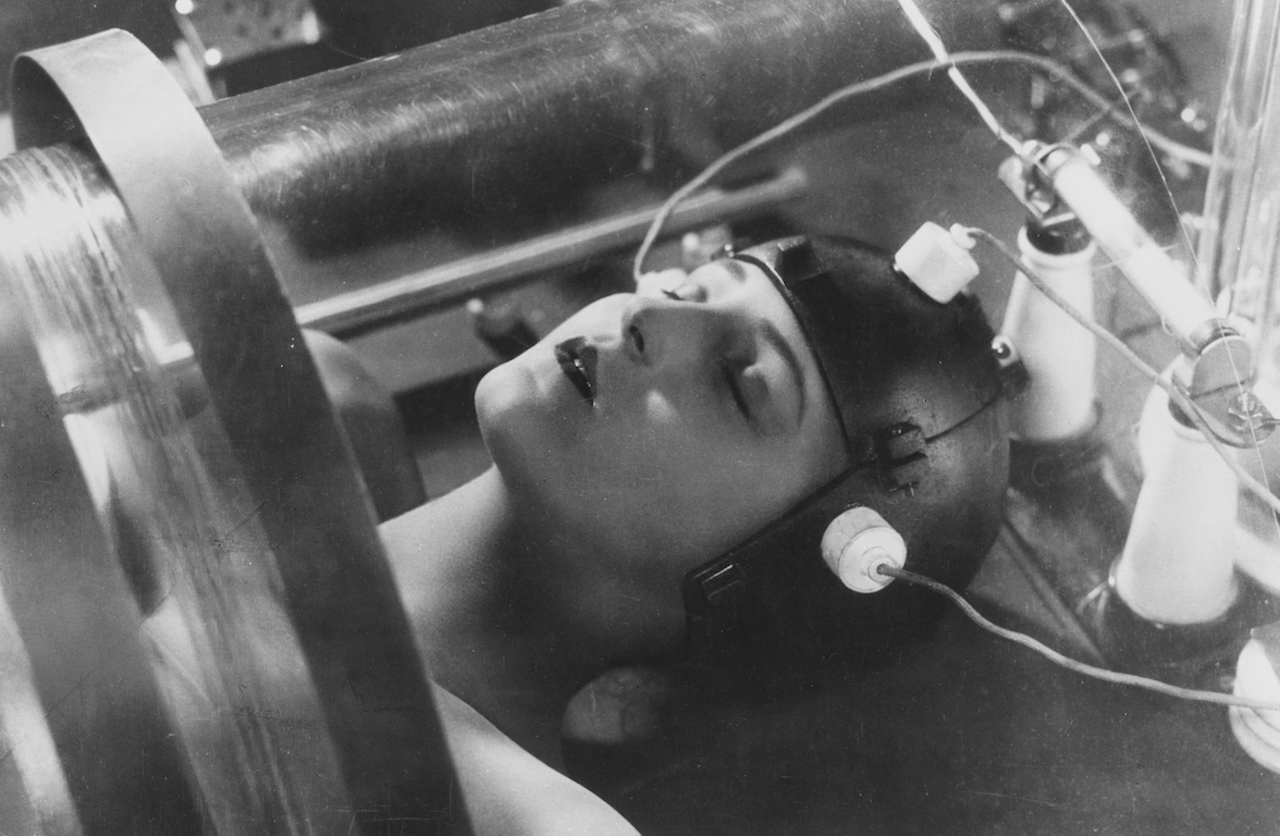

The film focuses on Jackie Kennedy (Natalie Portman) in the aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s assassination as she struggles to put her life back together and ensure his legacy. Before any shots of the film, Mica Levi’s moody, haunting score sets the tone. The music signals the film’s interest in the grotesquerie that comes after violent death. Levi uses many of the same techniques she demonstrated in scoring the sci-fi horror film Under the Skin — glissandos, “quivering tremolo strings,” and a sonic landscape that exemplifies an undertow of disquiet.

“It elevates the surreal elements because music creates a layer of fantasy,” Levi told NPR. When Jackie gets off Air Force One in Dallas with JFK (Caspar Phillipson) trailing behind, her face contorts amid her practiced smiles as if she’s overwhelmed, even afraid of the demanding crowd encircling her. Larraín chooses to have the score take precedence over diegetic sounds, giving the scene a claustrophobic edge. And during the grand funeral procession Jackie fought to pull off, the score isn’t only mournful — it’s menacing. Coupled with Portman’s sad eyes that occasionally dart upward to the balconies lining the street, it suggests that danger is always imminent, heightening the tension. The movie deviates from other biopics that favor a fawning replication of the Camelot myth above all else. In turn, Larraín’s film does something entirely unexpected: It makes Jackie feel like a flesh-and-blood human being we haven’t met before.

Alfred Hitchcock once said, “There is no terror in the bang, only in the anticipation of it.” In Jackie, JFK’s assassination is never shown fully and uninterrupted. The film moves back and forth in time, anchored by Jackie’s vaguely antagonistic, acidic-humored interview with Life reporter Theodore H. White (Billy Crudup). Instead of taking the more traditional route of chronologically showing everything from when they arrive in Dallas to Jackie deliriously stumbling through the hospital and happening upon her husband’s autopsy, Larraín parses the actual event out. It’s almost like watching a more artful version of the 1960s horror films starring Bette Davis that trained their gaze on the ways women buckled under the expectations thrust upon them.

Glimpses of the moments surrounding the shooting are peppered throughout the film, like Jackie adjusting her pillbox hat on the plane and her refusal to change from the suit, wanting everyone to bear witness to her grief. In doing so, each time we see Jackie in the pink suit there is an uneasy expectation of witnessing the actual assassination and not just the events surrounding it. It isn’t until much later in the film that Larraín does so. We hear the gunshots rip through the air. The motorcade races down the highway, blood and brain matter coloring its hood. With Kennedy slumped over in her lap, Jackie tries to hold his shattered skull together with blood pooling around her. Showing such unflinching gore is an audacious albeit not altogether unprecedented choice. The 2013 film Parkland wasn’t afraid to get bloody either. But what separates Jackie from the countless times pop culture has recreated the assassination is how deeply the film grounds itself in her mind and experiences. Rather than opting for a sanitized, simplistic repetition of facts biopics usually provide, Jackie binds its structure to a throughline of her emotional terror. When we see her recent past it feels not like what exactly happened, but her warped memory of events.

Throughout most of the film, Kennedy is seen on the edge of the frame rather than in full. Part of a smile. The back of his head. His profile as he spins Jackie on the dance floor. It makes him feel like a ghostly figure, an aberration haunting Jackie and the film itself. Jackie moves between moments of bloody violence and its horrifying aftermath, eerie stillness and profound sorrow — all of which is filtered through Jackie herself in a way that always keeps us on edge. This approach puts Jackie in a pantheon of films, many of which are horror, that detail unraveling women undone by tragedy. Their own hysteric, grief-stricken, and hyperreal mentality often defines the mood, tone, and structure of their films.

Jackie binds its structure to a throughline of her emotional terror.

This cinematic tradition includes works like Gaslight, The Babadook, Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, and Black Swan, which nabbed Portman an Academy Award for Best Actress. Black Swan and Jackie share much in common from the pervading sense of doom to an interest in the theatricality of gender presentation. But Black Swan is a morally murky, high camp work that never seems sure if it wants us to empathize with Portman’s deranged ballerina or mock her naïveté. Jackie has no such contradictions. It’s firmly on Jackie’s side, acknowledging her prickly complexities and arguable unlikeability without condescension.

Portman has a face made for close-ups. It’s often the fear marking it that most deftly communicates the panic of these events, like when Jackie wipes Kennedy’s blood from her face with frantic desperation. The camera also often encircles Jackie to an almost dizzying degree, giving moments an unexpected claustrophobia and unease, and casting her like a bird trapped in a gilded cage. When Jackie isn’t overwhelmed in the frame she’s surrounded by empty space that has a different quality of suspense — one prolonged shot of her staring in the bathroom mirror while packing up her belongings to move from the White House is the kind of shot that is so common in horror it borders on cliché. It stays on her so long that I half-expected a dark figure to emerge behind her bringing the internal demons she wrestles with into reality. “What I wanted to do is take the film into a non-realistic place. It’s more psychological than emotional,” Larraín said to NPR.

Visceral and gory violence is not the bedrock of effective horror. It's the way a character handles its lingering psychological presence, even after bloodshed, that leaves a mark. When Jackie finally gets back to the White House after Kennedy’s death, Larraín takes his time showing her undressing. She gently peels off her stockings marked by drying blood and dumps the suit on the floor. In the shower, blood trails down her delicate back as a final, unflinching reminder of what she’s coming from. Watching Jackie finally alone in the White House, particularly in a later dress-up scene, brings to mind Jack Torrance (Jack Nicholson) strutting around the Overlook in The Shining. But Jackie is a more intimate affair than Stanley Kubrick’s classic. If Torrance is toxic masculinity come undone, Jackie is female steeliness stitching itself back together. Jackie may not be an outright horror film, but it embodies the ethos of horror in ways that reminds viewers why it remains such a captivating genre.

We don’t go to horror films just for the fleeting thrill of jump scares or the shock of seeing inhuman monsters. At their best, horror films bring to life the contradictory, ugly, and transcendent aspects of human nature. They represent our deepest fears and darkest desires, writ large. In Jackie, that is the soul-warping nature of grief and the desire to control our own narratives in the aftermath of loss.

Gory violence is not the bedrock of effective horror. It’s the way a character handles its lingering psychological presence.

The traits Jackie has become most known for are still there — that odd lilting voice, a practiced physicality that acknowledges what it means to always be watched as a woman, and a keen understanding of what the titles of wife and first lady mean not just materially but existentially. We can see in Jackie the kind of woman who is not so much raised but bred. But there are unexpected ripples in how Portman sells Jackie’s intelligence, cunning, and barbed-wire humor. This easily could have fallen into caricature or been too studied, although it’s clear Portman did her homework. But the achievement in Portman’s work isn’t how it mirrors reality — it’s the psychological portrait she creates that melds personal grief, and an understanding of the symbolism Jackie constructs for herself.

Portman knows how to make an icon feel real in ways Jackie has never before been on film. She is an actress who operates best at a higher pitch. She eschews the modern preoccupation that many actors have for more muted, naturalistic displays of emotion for something richer and more heightened. This is most evident in a scene halfway into the film in which Jackie dresses and undresses in the most beautiful, lush pieces from her wardrobe. She drinks an impressive array of alcohol all the while slinking through the White House as the soundtrack for the musical Camelot plays. It is the most moving demonstration of the hellish spiral that Jackie finds herself mired in and how she hasn’t only lost her husband but her entire way of life in the process. Portman brings a luminous intelligence, anger, and depressed edge to this scene, which acts as the film’s emotional thesis.

Jackie finds hidden contours in a well-worn icon by framing her story with creeping suspense. Ultimately, it turns the story of this time in Jackie’s life into a bold mix of gothic horror and arch drama that may not be literally accurate but feels emotionally true. We know historically how the real story ends. But as Jackie shambles through Air Force One, the hospital, and the White House, defiant in her refusal to discard the pink Chanel suit stained in her husband’s blood — her reverie warped by grief — there is the haunting possibility that maybe this time she won’t survive the nightmare.

A previous version of this story inaccurately referred to Jackie's iconic pink suit as a dress.