Back in October 2016, researchers at George Mason University published a report on the peculiar distribution of airport noise complaints. Across the country, the vast majority of complaints about aircraft noise tended to come from a handful of residents. In Seattle, three individuals accounted for 64 percent of all complaints in 2015. In Denver, four individuals accounted for 96 percent of complaints the same year. But the most lopsided figures came out of Reagan International Airport in Washington, DC, where authorities claimed a single individual was responsible for 6,500 complaints in 2015, more than 75 percent of the total figure (8,670).

Subscribe to Sound Show here

If true, some Washingtonian was filing on average 18 complaints a day — every day — for 365 days. Could a number like that even be accurate?

“It’s got to be a full-time job,” said Eli Dourado, the George Mason researcher who co-authored the “Airport Noise NIMBYism” report with Raymond Russell. “I am not qualified to evaluate them in any way, but it does seem,” Dourado paused before finishing, “they're clearly suffering.”

Dourado didn’t know who the complainer was. No one did. Well, the airport did, but it wasn’t snitching. All officials were willing to say was that the complaints were coming from a household in Foxhall, an otherwise quiet neighborhood near Georgetown University and more than five miles away from the airport.

The tale of the mysterious serial complainer culminated in a Washington Post article titled “Are you the person who filed 6,500 noise complaints against National Airport?”

No one raised their hand.

Who was it? Was that number right? And were their complaints warranted? I wanted to find out.

Roberto Vittori reached out to me directly while I was researching this story. He had seen an email I'd sent to the Airport Noise Liaison of the Foxhall neighborhood association asking about the complaints.

Vittori’s dogged persistence single-handedly increased the number of noise complaints in DC by an astounding number, though he rejected the notion that he had personally sent 6,500. He spent countless evenings and weekends in 2015 filing noise complaint after noise complaint, like someone who has the bad fortune of moving in next to a rowdy fraternity house.

“This is already as I am describing it, you can have the flavor, a full-time job,” Vittori, a 52-year-old Italian citizen and resident of Washington, DC, said.

It wasn’t always like this. In 2013, when Vittori moved his family from Italy to Washington, DC, he thought his wooded neighborhood nestled behind Georgetown’s campus was idyllic. He bought the house knowing full well there would be some noise overhead, but at the time it wasn’t something to complain about. And then it got worse.

Shortly after Vittori moved, Reagan International shifted to a new flight navigation system known as NextGen. This multi-billion-dollar upgrade was developed to help cut carbon emissions and reduce how much fuel is used by providing airline pilots with more direct routes between origin and destination. The NextGen system plotted a new route for planes coming in and out of the DC airport that was closer to Vittori’s backyard.

“From my bedroom I can see all the planes, and I can very easily identify them by sight,” Vittori said. “However, I can also identify them by the noise,” he added.

The Boeing 737’s are the worst. Vittori compared the engine noise to having a vacuum cleaner next to your bedside. “Can you sleep when a vacuum cleaner is turned on?” he asked. “You cannot. You wake up.”

“Can you sleep when a vacuum cleaner is turned on? You cannot. You wake up.”

Vittori spent thousands of dollars installing half-inch-thick windows throughout his house. But his efforts to mitigate the low frequencies emitted from plane engines were futile. Vittori says the sounds can get up to 80 decibels (the legal nighttime noise limit in Washington, DC is 55 decibels) and penetrate walls and windows.

When replacing his windows didn’t work, Vittori started sending noise complaints to the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority (MWAA). Very detailed complaints.

An example:

“Note of the case of American Airlines 585, on the 7th of October 2016. At a speed of 361 mph, with a simple calculation the airspeed can be approximately 300 knots well in excess of the 250 knots limit. Excessive speeds implies excessive noise. That’s something we keep addressing to your attention that this is completely unacceptable in our local community. Thank you very much for considering.”

The technical language used in the complaints are a holdover from Vittori’s former career as an astronaut with NASA and the European Space Agency. He’s been to space three times and as recently as 2011. He has his own Wikipedia page. At 52, he looks like he could pass a physical any space agency could throw at him tomorrow. Now he has a full-time job working on issues related to space policy between Italy and the United States.

Vittori spent a significant portion of his adult life preparing for some of the most extreme conditions known to mankind, so it’s surprising he would have chosen aircraft noise as his hill to die on. But as Vittori describes it, the noise has taken a devastating toll on his health — both physically and psychologically.

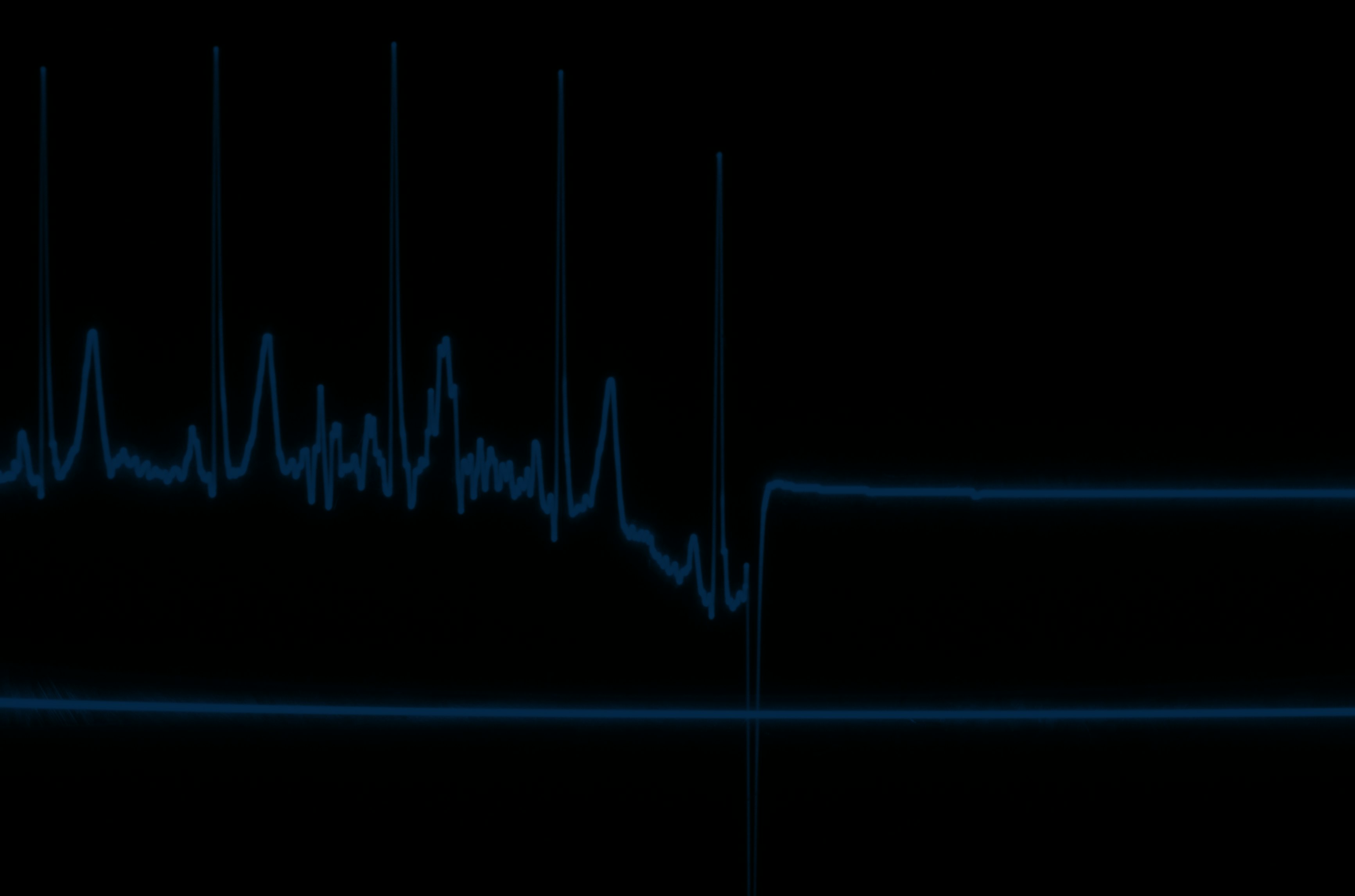

“It creates anxiety, stress, you feel your heartbeat increasing,” he said.

Was Vittori the person who submitted those complaints? He says no.

Vittori believes the airport is conspiring to write him off by inflating the number of complaints he actually made. While airport authorities say the most frequent complainer made 6,500 complaints in 2015, Vittori is adamant that he made around half that amount. After all, “there is a physical limit to the number of complaints that you can do,” Vittori said. But even at 3,000 complaints it would put him light years ahead of the next most frequent complainer who only made 352.

“There is a physical limit to the number of complaints that you can do.”

“When you get into a routine you know the difference between 10 and 20 [complaints per day],” said Vittori.

If you believe the reported numbers, in addition to Vittori’s 3,000 or so complaints, there is a Foxhall resident who made another 6,500 complaints. If those numbers are right, it would mean the airport vastly underreported the total number of complaints in 2015 (8,670 instead of approximately 11,670).

Another quirk is that airport authorities maintain that the person who made 6,500 complaints lives in Foxhall, a neighborhood west of Georgetown University. But Vittori lives in Hillandale, which is the neighborhood north of Georgetown.

To settle things once and for all, Vittori emailed airport authorities under the Freedom of Information Act and asked point blank if he was the person responsible for the 6,500 complaints.

According to a letter Vittori received back from the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority, he is not the sender of those 6,500 complaints. His number of 3,000 or so seems to be closer to the truth.

Eli Dourado says there are ways to reduce aircraft noise. But he also said it doesn’t make sense to create policies based on the concerns of a few upset people who are sensitive to noise.

“One way to avoid some airport noise is to take off with a lower throttle, which is less efficient and creates additional carbon emissions,” said Dourado. He also pointed out that based on objective data from noise monitors positioned throughout the city, the number of complaints coming from an area isn’t correlated with how loud it actually is. Meaning, as bad Vittori thinks he has it, someone else has it worse.

Peter Watkins, 60, is a long-time resident of Foxhall. He files a couple of noise complaints each week and sympathizes with Vittori’s one-man protest against the MWAA.

“I've had certain days where [the noise] really got to me when I was trying to focus on something,” said Watkins.

On the website for Foxhall’s Community Citizen’s Association, underneath a section related to airport noise, a statement says:

“It is extremely important that all Foxhall residents continue to log complaints through 2016. In a similar situation, communities in California logged over 50,000 complaints. Please encourage as many individuals to log as many complaints as possible — about anything.”

Vittori doesn’t file complaints anymore. Not because he thinks the noise has diminished, but because he’s convinced there is no grease to be had for this squeaky wheel.

“This is completely hopeless,” Vittori said. “There will be no change.”

The official noise complaint numbers for 2016 haven’t been released yet, but with Vittori under a self-imposed silence MWAA should expect the total number to be far lower.

In the meantime, Vittori is trying to move on. Literally.

“I will move because I consider this type of stress inappropriate for the quality of life, for decent health standards for anyone,” he explained. “I will have to move elsewhere because of the long-term impacts.”

From Vittori’s point of view, complaining was the only way he knew how to draw attention to an issue that he genuinely believed could have benefited from closer inspection. He may have been wrong about that, but being wrong isn’t what keeps him up at night.

Update: This story has been updated to reflect information Roberto Vittori received in the form of a letter from the Metropolitan Washington Airports Authority. The letter states that Vittori is “not the individual that submitted the approximately 6,500 aircraft noise complaints to the Airports Authority.” Vittori places his number at closer to 3,000 complaints in our interviews, as stated in the article.