In case you hadn’t heard: the side hustle is over, and the multi-hyphenate has taken its place.

“This is about choosing a lifestyle. This is about taking some power back into our own hands,” writes Emma Gannon in the introduction to her new book, The Multi-Hyphen Method. She goes on to explain that, despite the lament of the gig economy and the exploitation of contract workers, with a “plan of attack” we can find a “mishmash” of “different income streams” and become “a career chameleon.”

The multi-hyphenate, an individual with so many skills they need multiple hyphens to list them, might seem like a revolutionary form of labor agency within a prescriptive job market, especially when it presents as Gannon’s writer-broadcaster-podcast host dream career. But the term inherently privileges certain skills over others, particularly those of knowledge workers who often hold secondary degrees, and idealizes a form of labor that becomes absorbed into personal identity, diminishing work-life balance and generating further barriers to worker solidarity.

Issues of multi-hyphenate alienation have existed since the concept was invented. The term “multi-hyphenate” originated in the 1970s, and was deployed mostly in Hollywood. First used to refer to celebrities and artists who fell outside the traditional notion of a “triple threat” — singing, dancing, and acting — it’s not hard to imagine how the New Hollywood era would give rise to such creative grandeur. As directors played a greater role in their films, literally editing and starring in them, previous divisions on production teams dissolved. A 1988 Los Angeles Times article on the Writers Guild of America strikes described some of the workers as “hyphenates,” or “people holding dual jobs whose titles include hyphens.”

Blurring the distinction between labor and management would prove problematic. Combination writer-producers made for noncommittal strikers, generating schisms along the picket line that prompted an internal movement to restructure, aiming to make hyphenate-identifying writers observational, non-voting members. Meanwhile, the hyphenates interviewed cited “job security” as their main motivation, and over time as more workers sought hyphenation within the competitive sphere of Hollywood, common dualities like writer-producer could no longer do such creative genius justice. Thus, the more encompassing “multi-hyphenate” was born.

Multi-hyphenates are one of those things that’s hard to stop noticing once you start; look around the room at a party and it’s a challenge to find someone with a singular career. Within popular culture, actor-singer-etcetera celebrities like Rihanna, Donald Glover, and Jennifer Lopez are defined by their endless accomplishments. But further downstream, the notion of work has shifted away from simply doing a job to building a career, and the hyphen has become shorthand to conflate personal identity with professional capability. The rise of the “multi-hyphenate” has ironically eliminated the need for any specificity at all, instead implying a complex creative identity grounded in a jack-of-all trades ideal that conflates production potential with individual worth.

This movement away from specialization, or toward “chameleonization,” as Gannon might have us believe, counters the ideology of industrialization, in which workers engage in the division of labor to speed up production. Commonly known as “Fordism,” after the mass assembly methods employed by Ford Motor Company in the early 20th century, this practice largely created the economies of scale that now provide us with consumer choice, opening up new opportunities for more creative or intellectual work.

Max Shock, a doctoral candidate and intellectual historian at Oxford University, told me that “post-Fordism” or “the shift to ‘flexible specialization’” was initiated by employers, but ultimately posed a greater cultural impact. “I suppose you could view multi-hyphenates now as part of that wider process,” he said, “of post-industrial societies shifting to ‘knowledge economies’ where the emphasis there, too, is on this notion of flexibility.”

But mere “flexibility” doesn’t fully capture multi-hyphenism. Nicholas Henderson, a Ph.D candidate at the University of Minnesota, pointed to Italian philosopher Paolo Virno’s theory that in recent years capitalism “has taken into the production process forms of labor that are purely intellectual [and] basically do not exist in the form of a material product.” Virno called this “virtuoso labor,” a term Henderson explained to me as “any kind of labor that is [...] essentially just a performance.”

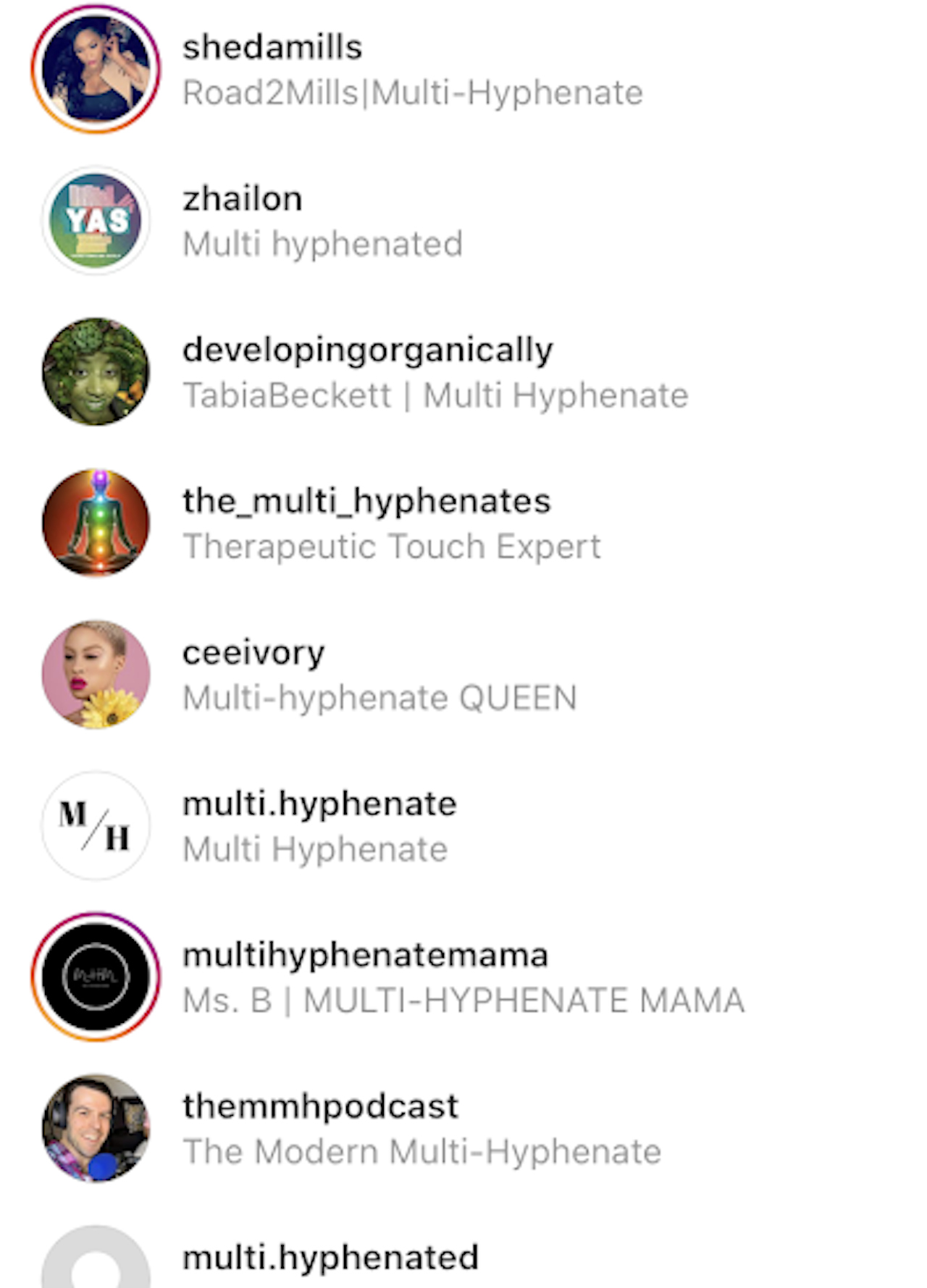

That the next iteration of the labor market is based on performance and content production seems inextricable from the realities of the internet era. In my own research, most of the individuals I found who identified as multi-hyphenates in their Twitter or Instagram bios could also be considered “virtuoso laborers,” working as podcast producers, photographers, writers, marketing strategists. All are professions that imply an audience. With the internet came an online culture industry, which ultimately became a scramble for monetization through the proliferation of clickbait and branded content.

I asked Henderson, whose research focus is in the political economy of digital media, about the act of defining oneself as a “multi-hyphenate” online, and whether that might be an attempt to brand oneself as employable. Instead he pointed to the production of this content, suggesting that the use of the “multi-hyphenate” label in online spaces “actually betrays this sort of anxiety over what we are really seeing in the homogenization of all forms of content production.” Because every producer is working with the same online platforms, there are limitations to what content can be distributed and rewarded. Henderson proposes that some of the desire to self-identify by many titles is a way of “grappling with and insufficiently trying to compensate for is that all those forms of labor increasingly look like the same thing.”

This idea of a melding of content reminded me of one of the multi-hyphenates I spoke with, Ellie Pritts, who founded the creative marketing agency, Supermassive Social, to take on projects that would combine her skills as a photographer-director-producer. When I asked her about the way she uses her different titles, and why she chose to self-identify as a multi-hyphenate, she indicated that it felt almost inevitable, and the title became one of convenience. Known for launching Apple’s Instagram, Pritts has since worked on campaigns and productions for celebrities and companies alike; simply put, she has created a content production firm.

But with the creation of social media, content production no longer requires a team or corporation to pool skills and resources. Instead we see individual creators and online “influencers” as full-fledged producers, curating personal brands that cross-function as endorsements of skill. “Part of what we do in cultivating online identities is kind of like auditioning to be accepted as whatever kind of role we want to assume,” Henderson told me, citing feminist scholar Sianne Ngai’s theory of the zany, an aesthetic of labor that involves a comedic performance of the worker. Take Ngai’s example of I Love Lucy. Many episodes involve Lucy trying on various forms of labor, from working in a chocolate factory assembly line to temping as a secretary to training as a ballerina. Her flexibility makes her hilariously incompetant, overwhelmed, and frazzled. The theory goes that the worker is “pushed to the brink of flexibility necessitated by the market and almost put themselves in dangerous, perilous situations to achieve this flexibility,” Henderson said, “And it’s funny for the audience to watch.”

So what compels regular people, that is to say, those without an explicit audience or online “brand,” to identify under so many titles? I followed up with Shock to consider whether that post-Fordism flexibility could be driven by a more competitive job market. “It might be possible to consider hypothecation in some instances as simply precarity, that the reason people end up taking on a number of roles is because some jobs simply don't pay a living wage,” he confirmed. Consider the worker who drives for Uber and cleans houses, or the restaurant server who works retail during the day; “that’s a far cry from, for instance, those at the top of creative industries (your writer-director-producer-actor), Shock said.”

There is a connection between the work performed by more specialized, factory or industrial workers, and the freedoms enjoyed by knowledge workers.

He wasn’t the only one to point out this distinction between creative industries, often spaces of immense privilege, and other contract workers like those working for Uber, Amazon, or in service industries. In fact, every researcher I spoke with questioned this inclination to elevate what is, simply put, the need to hold down multiple jobs — though for many modern multi-hyphenates, the appearance of having multiple jobs outweighs the actual need to do so. Not to mention the fact that this supposedly desirous flexibility, in the case of multi-hyphenates with “chosen” careers, is the result of living in a country that has already achieved the wealth and scale of production necessary to provide space for more intellectual pursuits. Meaning that there is a connection between the work performed by more specialized, factory or industrial workers, and the freedoms enjoyed by knowledge workers unbound by the constraints of the consumer market. Which isn’t to say that writers or directors are not beholden to the demands of the market, but rather that “multi-hyphenation” as a title is not universally accessible; it implies a certain intellectual capital inherently tied to wealth.

From a certain vantage point, multi-hyphenation can seem like a glamorization of precarity. It’s hard to listen to Gannon talk about choosing a lifestyle when, for many, there is only one lifestyle option and it’s survival. It’s harder not to roll my eyes at “taking back power” when the multi-hyphenate is making commodification of the self under capitalism not only acceptable but enviable. It speaks to a greater phenomenon in which the human desire for self-improvement and common identity is co-opted by capitalism; self-care becomes compulsive shopping, LGBT Pride becomes a corporate marketing ploy, and creativity is a measure of one’s ability to self-brand.