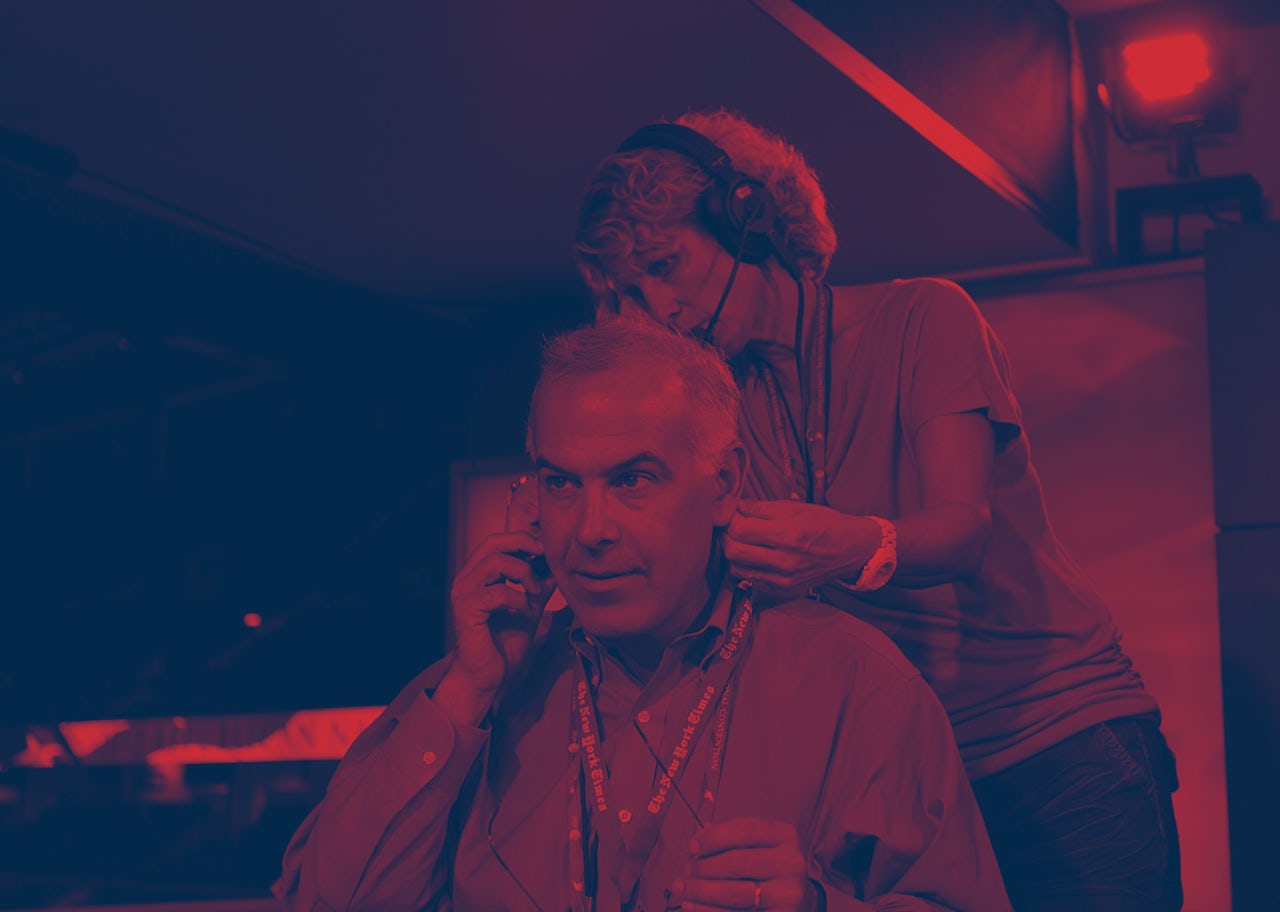

What does New York Times columnist David Brooks do when he’s not writing? According to his September 27 piece, “Yes, Trump is Guilty, but Impeachment is a Mistake,” he spends his time lightly bending the space-time continuum. “This week,” he wrote, “I was in Waco, Nantucket and Kansas City. I had conversations or encounters with hundreds of people. Only one even mentioned impeachment, a fellow journalist.”

Who are these hundreds of people, and how long did Brooks talk to each of them for? Did he actually ask them about impeaching Donald Trump? We do not know, and we may never find out. But in mentioning them, Brooks is able to deploy a columnist’s favorite literary device — the use of unnamed people and conversations to create distance from one’s own opinions and instead play the role of messenger, passing along the opinions of others who just happen to have the same opinions as you. For Brooks, who has been a Times columnist for 16 years, the discourse is what it is and elites — both Democrats in Washington and the ravenous left-Twitter horde — need Brooks to see what is real.

Brooks [once] falsely claimed that it was impossible to spend more than $20 on a single meal at Red Lobster.

Brooks’s conversation partners may well be fictional, but at least the pieces they appeared in weren’t outright fiction — a form that Brooks turned to not once but twice in the past month. It’s tempting to dismiss Brooks’s recent literary experimentation as another example of an aging Times columnist behaving bizarrely in an attempt to remain relevant, there’s more to this narrative experimentation than first meets the eye. It shows Brooks’s conservative centrism in a moment of profound crisis, only able to articulate its value through the negation of other, putatively “extreme” positions. So his experimentation points to a question with which he himself seems to be struggling: What is the point of individual “opinion” writing if one’s centrism is not a positive ideological commitment, but rather a formal posture that can only define itself in response to the ideas of others? And Brooks is supposed to write two pieces of opinion writing a week! This leaves no other option for him but to turn completely to remedial creative-writing exercises in order to somehow escape from the intellectual prison into which he’s typed himself.

Let’s begin by taking a look at Brooks’s September 5 column “And Now, a Word From a Fanatic,” which just about encapsulates every challenge faced by centrist opinion writer in this moment and reveals the profound poverty of the conservative imagination. The column reimagines Fyodor Dostoevsky’s 1864 novella Notes From Underground as a trip “inside the mind of an internet extremist.” Brooks’s fanatic is somehow a composite of “the ones who make online forums so vicious, the ones who cancel and call out, the minority of online posters who fill the air with hate.” The fanatic is objectionable first and foremost for his rude behavior, to which Brooks attributes a personal sense of alienation stemming from “the permanent flux of liquid modernity” that finds satisfaction and closure only in “the single narrative that will make everything clear.” Brooks moves between describing the speaker’s desire to “Own the libs! Smash the racist right!” and lamenting the speaker’s profound, totally real loneliness.

This character is, naturally, absurd. He affirms conservative talking points about the necessity of tradition and genuine moral order even in his — as Brooks sees it — nihilism. Sloppy politics aside, the column is a devastating attack on Brooks’s own intellectual style if we consider it in the broader context of his body of work. Brooks has not always been a centrist. He spent the better part of his pre-Times career defining his conservatism as a check on the liberal philosophy that emerged from the Enlightenment, in which people were self-directing individuals essentially free from social institutions and hierarchies; his consistent lament has been that the state — in its various 20th century forms — has encroached upon organic “orders” that he sees as ideally local, idiosyncratic, irrational, and capable of adapting to historical change on their own terms. In Brooks’s view, national and global cultures threaten the organic connections between individuals, replacing local processes of care and communal flourishing with consumerism and “identity politics” that alienate individuals from each other.

Brooks has described this alienated individual before. His name is Patio Man. Brooks first introduced Patio Man to the public in a 2002 Weekly Standard cover he wrote titled “Patio Man and the Sprawl People (reprinted here) as a victim of the urban elite’s flight from the city to the suburbs; he re-emerged in Brooks’s Times column on the eve of the 2008 election. Patio Man is a white, America-loving, Christian, traditional, and un-self-conscious suburbanite. Brooks describes Patio Man’s fantasy of throwing a barbecue at his home in a Republican-leaning suburb, working a grill “to the silent admiration of all” while his wife “Cindy, a Realtor Mom,” plays host. (It goes without saying that there are a lot of holes in Patio Man — and that the greater style of comic sociology that Brooks practices relies heavily upon false dichotomies, suppression of inconvenient facts, bizarre embellishments, and outright fabrications; most incredibly, the journalist Sasha Issenberg discovered that Brooks had falsely claimed that it was impossible to spend more than $20 on a single meal at Red Lobster.)

The world Patio Man built has failed.

Patio Man allowed Brooks a plausible everyman who just wanted life to be simple — an essentially inoffensive stereotype that could embody broader social tendencies. Yet Brooks’s take on Dostoevsky bashes the fanatic’s tendency to reduce individuals to stereotypes. “People are not defined by individual traits but by group ones,” he imagines this online extremist saying. “Individual persons are too complicated, but groups are abstract and easy to stereotype. Every human being gets reduced to some category, preferably the cunning ones I despise: the libs, white males.” Stereotypes, it seems, may only be bad when Brooks doesn’t agree with them.

The fanatic’s tendency to describe his own alienation through the language of conservatism signals a deeper point about Brooks’s inability to fully imagine the stakes and structure of this moment in American politics. The column’s thin premise — that the fanatic is who he is because society’s institutions have broken down — is the same one from which Brooks’s writings tend to proceed. The fanatic is Patio Man’s maladjusted son. The world Patio Man built has failed, but Brooks is still here arguing that Patio Man’s values will save us, even as the column reveals a terror that there is no going back. The fanatic exposes the fact that centrism is itself as much a nihilistic dogma as those others that Brooks disdains. The fanatic’s racism or anti-racism, his sexism or feminism, his faith or atheism, are essentially meaningless. “My politics is not really about issues,” Brooks writes. “It’s epic wars for recognition. I don’t deal with the complexities of economics or foreign affairs.”

Brooks’s conservatism stems from a refusal to acknowledge the political dimensions of cultural institutions, and so he cannot admit that other forms of community based on other approaches to ethical and political commitment have formed and in fact have always existed in the U.S. And so he undertakes a thought experiment to get inside the mind of people he cannot allow himself to understand, and finding only the vacuousness of his own politics, he fills the void with himself: “Somehow politics doesn’t fill my soul, bring me peace or end my existential anxiety. I have helped create a harsh world in which vulnerability is impossible and without vulnerability there can be no relationship. Relationship is the thing that I long for the most and that I make impossible. I have cut myself off from the only thing that can save me.”

Two weeks after the fanatic, in a column titled “A Brief History of the Warren Presidency,” Brooks pretended to be writing from 2050, looking back on 30 years of radical swings in national political orientation under and after a President Elizabeth Warren: first away from right-wing populism towards left-wing populism, then from an exhausted left-populism to a “moderate liberalism” which, once and for all, restores order to American culture’s “faith in capitalism and the Constitution and... the classical liberal philosophy embedded in America’s founding.” The column argues that the current moment in U.S. politics is marked by “culture, class, and demographic warfare” and that the future will belong to “coalition-builders not fighters.” Again, we see Brooks’s conflict aversion and moral equivocation. When he has to get into the nuts and bolts of what moderate liberalism offers, Brooks again projects his own shortcomings on his opponents. Describing the imagined failure of the Warren presidency, he explains, “fired by their sense of moral superiority, they were good at condemnation, not coalition building.” Look again at the hideous phrase “demographic warfare.” Brooks’s implication seems to be that politicians and movements critical of racism are unjustly waging war against white people. Or that advocates for gender equity or a full set of rights and legal protections for LGTBQ+ people are unjustly waging a war against cisgender heterosexual men.

By casting genuine political movements emerging from the real, lived experiences of millions of people as mere demographic difference, Brooks again obscures power relations by making both sides in struggles for social and economic justice appear parochial and cut off from what is supposedly “real” about life. White supremacists are motivated by misguided notions of racial superiority, but so too, apparently, is anyone who opposes them. Yet the obfuscation does not happen by equivocation alone. Brooks evidently takes a swipe at the Times’ massively successful 1619 Project when he criticizes progressives, who believe “that the founding [of the U.S.] was 1619, not 1776,” and “were willing to step on procedural liberalism in order to get radical change.” What does coalition look like between people of color and anti-racist whites? It looks like current movements to take down Confederate monuments, end mass incarceration, and raise the federal minimum wage. These are divisive issues, though, and so appear as “warfare” against the defenseless beating heart of authentic society: “procedural liberalism.”

Despite his mild protestations about civility and discourse, [Brooks is] basically unbothered by the contemporary right.

Brooks’s faith in procedure is of a piece with his other investments in formal, abstract definitions of humanity and community that underpin his approach to the world. This faith in the moral value of any institution whatsoever complicates the grand narrative of this particular column in a way that clarifies why Brooks is, despite his mild protestations about civility and discourse, basically unbothered by the contemporary right. If moderate liberalism is to triumph, then he is justified in not taking a firm stand on any particular issue. Yet there’s also a sense that a Warren-like left-populism (for the purposes of this argument, let’s accept Brooks’s premise that that’s what Warren truly represents), is a necessary cleansing fire. The column reads as a centrist-accelerationist endorsement of Warren: heighten the contradictions so that… they can be peacefully resolved by the silent majority ten years down the road. In the end, the triumph of moderate liberalism doesn’t even happen because the ideas themselves prove valuable.

Instead, Brooks imagines demographic transformations that squash the (as he imagines it) small but vocal minorities on the right and left. To sweeten the deal, Brooks imagines non-white citizens authoring this moment of triumph. “It turns out that immigrant groups,” he fantasizes, “by then a large and organized force in American politics, had not lost faith in the American dream, they had not lost faith in capitalism.” Immigrants arrive to save the day, motivated by the ideals of the American dream, not by growing regional instability caused by decades of U.S.-led economic imperialism and climate crisis. At every level, Brooks’s writing evades confronting the way institutions fail to produce the egalitarian free society, using the presumed ignorance and/or idealism of others to justify what is, at its core, a morally and intellectually bankrupt death grip on the remaining privileges still afforded white men in American society.

Brooks’s coercive fictions intensify the dynamic of wish-fulfillment that has always accompanied conservative politics, inventing new threats to institutions that (in Brooks’s mind) have been under attack for decades but that (in reality) have unjustly shaped the lives and possibilities of people not like Brooks since before the nation was founded. Brooks will continue writing and shaping the discourse of the contemporary center, providing fodder for the bloviations of never-Trump Republicans and moderate Democrats alike who, sensing they have little else to offer, have been left arguing that the pre-Trump status quo is the only social arrangement capable of bringing about shared economic prosperity and religious and ethnic pluralism. Brooks should ask Patio Man if that’s what he wants from the 2020 elections. My guess is it isn’t.