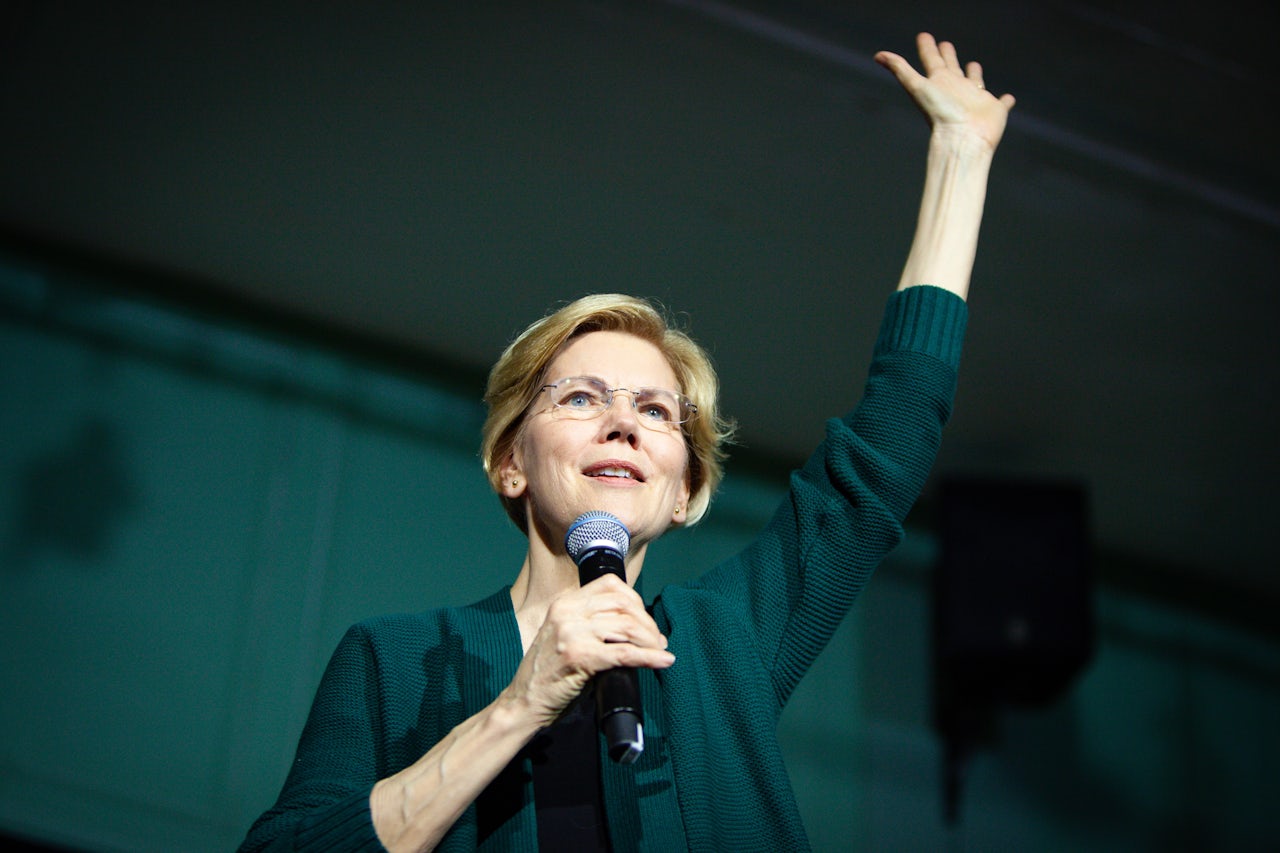

On Monday, the Working Families Party (WFP), a labor-aligned third party based in New York, endorsed Sen. Elizabeth Warren for president. The decision escalated a simmering conflict on the left wing of the Democratic Party between those backing Warren and those sticking with Sen. Bernie Sanders. In 2015, 87 percent of the WFP’s membership voted to endorse Sanders for president.

On its website, the WFP calls itself “a multiracial party that fights for workers over bosses and people over the powerful.” It’s a relatively small organization, with chapters in 15 states and Washington, D.C. But it punches above its weight. In New York, the WFP has played a significant role in pushing the Democratic machine to the left, endorsing progressives in primaries, and (sometimes) backing left-wing challengers to moderate incumbents. Rhode Island’s relatively new WFP chapter played an instrumental role in passing mandatory sick leave legislation in 2017.

The meaning of the WFP’s decision depends on where you sit on the leftward spectrum. On the one hand, self-identified “very liberal” voters — whom Sanders won by significant margins in 2016 — have moved toward Warren. These voters form a large portion of the WFP’s base. In this sense, the endorsement is merely a sign of changed terrain for Sanders in 2020, on which opponents of the party’s neoliberal wing have more than one candidate to choose from.

But for many Sanders supporters, the WFP has betrayed its principles. Bhaskar Sunkara, the founder of Jacobin magazine and former vice-chair of the Democratic Socialists of America (a group that has endorsed Sanders and of which, full disclosure, I am a dues-paying member), called the decision “baffling.” “Bernie is the national manifestation of the WFP’s politics,” Sunkara tweeted, “The fact that WFP doesn’t recognize that reflects how much it has strayed.”

Others pointed to the respective class compositions of the candidates’ supporters. “WFP endorsed a candidate with an overwhelmingly white, heavily professional base over a socialist with a diverse working class base,” journalist Daniel Denvir tweeted, referring to Warren, “This severely damages WFP’s relationship with the left.”

Sanders supporters have also taken issue with the process by which the WFP arrived at its endorsement. WFP told the press Warren had earned 60 percent of a membership vote to Sanders’s 34. To arrive at that figure, however, the WFP averaged the results of two separate votes — one among 56 party leaders and another of thousands of “members and grassroots supporters.” WFP Director Maurice Mitchel has declined to release separate vote totals, igniting suspicion among Bernie supporters that a small group of 56 party elites had subverted the will of “rank-and-file” members who might have preferred Sanders.

“WFP has a largely paper membership,” said Denvir on Twitter, “But it seems likely they couldn't convince that paper membership to support Warren and so are hiding vote totals.” By Tuesday, a change.org petition calling on WFP to release the vote split was circulating on Sanders Twitter. And on Wednesday, Sanders spokesman Mike Casca weighed in. “We respect the result of the WFP’s endorsement process,” Casca told the Washington Post’s Dave Weigel , “but we do believe they should release the final tally of both the board vote and the member vote, as they did in 2015. The inconsistency and lack of transparency is creating unnecessary division.”

The WFP fucked up its communications strategy — by repeatedly touting the transparency, democracy, and thoroughness of its endorsement process, they’ve put themselves in a necessarily hypocritical position.

I think it’s fair to assume the membership vote went for Sanders, otherwise the WFP would release it. But the conspiracy isn’t quite as nefarious as Bernie diehards wish it was. The 56 “party leaders” who make up the WFP’s national committee are representatives of the state chapters — some of them elected by the membership — and leaders of state and national affiliate groups, i.e. community organizations and unions.

Meanwhile, the “grassroots members” comprise effectively anyone who receives WFP emails. (I could’ve voted in the endorsement process; I haven’t been to a WFP event in four years. DSA could’ve organized its members to vote in the poll too.) The caricature of a nefarious cabal of party insiders undermining the will of the majority doesn’t hold up. To Sanders supporters, the 56 party leaders are akin to super-delegates, the unaccountable “floating” electors who they feared would steal the 2016 nomination from him. But to the WFP, these leaders are more like regular delegates — representing the collective will of many unions, membership organizations, and state WFP chapters.

“We understand some people are disappointed in the outcome,” WFP National Campaigns Director Joe Dinkin told me, “But for us, it’s important that every member has their voice heard — whether they're active online, in a state chapter or local branch or in community group or union. It seems wrong to allow anyone to drive a wedge between different parts of our organization or different groups of our members. Every candidate who participated in our process understood it before we started, and no one raised any skepticism until we got to a decision.”

I find this story a tad too sanguine. At the very least the WFP fucked up its communications strategy — by repeatedly touting the transparency, democracy, and thoroughness of its endorsement process, they’ve put themselves in a necessarily hypocritical position. If the party is so proud of the process, what’s the harm in releasing the numbers? Well, the harm is that the appearance of a discrepancy between leadership and membership will undermine faith in the outcome and, perhaps, in the organization itself. So… maybe it wasn’t a perfect process?

But in a way, the concerns about process are incidental to the more pressing question at hand — not how they came to endorse Warren, but why. Perhaps (as many of my DSA comrades would have it) political professionals are preternaturally timid; WFP leaders were convinced the less-radical Warren would have a better chance of winning the primary and defeating Trump. Or maybe they just like her better. In either case, this decision is quickly becoming a proxy war for a larger fight on the left, and it’s worth thinking clearly about how that can and should play out.

One of the pleasures of radicalism is a diminished necessity for nuance. I’m not being facetious; part of what it means to be radical is to perceive the dominant common sense for what is: an elaborate authorization for the maintenance of the status quo. There is little nuance in a strike, for example — the narratives it conjures are blunt and dualistic: bosses vs. workers, capital vs. labor — and there shouldn’t be. “No justice, no peace,” has no nuance at all. For radicals, nuance isn’t as vital as vitriol.

This perhaps is why I’ve been having such a shit time of it lately. I hate to be the one cautioning nuance; it feels like a narrowing of the radical imagination, an insistence to look at one’s feet instead of the horizon. I’ll lay my cards on the table: My fundamental goal is that either Sanders or Warren wins the nomination and defeats Donald Trump. That’s it. I personally prefer Sanders, and I intend to vote for him. But I like Warren and believe she is a committed liberal populist. Both of them would achieve some good things and try to do others. Both support single-payer Medicare-for-all (though Warren’s uncharacteristically vague plan has invited suspicion). And both of them are running to be the executive of the world’s largest military empire. Neither of their victories would change (or accomplish) the left’s fundamental, and lofty, task: dismantling American capitalism and ending its global hegemony.

My operating premise is that there is a much larger and more consequential gulf (in terms of policy, governance, and class allegiances) between Sanders/Warren and everyone else than there is between Sanders and Warren. Despite some valiant efforts, a contest between Sanders and Warren cannot be sensibly mapped onto the comfortably Manichean showdown between Hillary Clinton (an avatar of Third Way triangulation and neoliberalism) and Sanders (a committed trade unionist and social democrat). This is a different situation calling for a different analysis.

I agree with Naomi Klein that “Democratic power brokers” are hoping for a Sanders/Warren slugfest, in which the two progressives (and their supporters) knock each other out while the establishment quietly consolidates around Joe Biden or a fresh-faced moderate like Kamala Harris. I can never gauge the degree to which the brain-breaking debates on my Twitter timeline indicate anything at all about political reality, but the last 48 hours have definitely sucked.

My preference would be for left movement groups to remain neutral, or better yet, stake out an explicit provisional endorsement for “Bernie or Warren” — at least until a primary or two clarifies the conditions and stakes. In Splinter, Hamilton Nolan even offered some pithy branding for this position: “Eat the rich in 2020. Don’t worry too much about which fork you use.”

Politically minded people — which is to say, activists, organizers, and the Very Online — tend to make political judgments early and stick to them.

The argument from the WFP about starting the endorsement process early is this: the left movement infrastructure needs to enter the fray. By taking the first step, the WFP gives license to other groups to endorse — either Bernie or Warren — as well. “We see that a lot of folks are waiting it out because there was a crowded field,” Nelini Stamp, who oversaw the endorsement process for the WFP, told me. To her thinking, that’s a recipe for handing the nomination to Biden and perhaps the presidency back to Trump. “To beat Trump, we need a candidate with bold structural solution to inspire people. We had to a process, so that we can hit the ground running, and not just wait until the cards lay themselves out.”

The irony, of course, is that the reaction to the WFP’s decision may not exactly entice other left groups to join them. Sanders supporters of a strategic mindset likely know this and are deliberately inflicting maximum public punishment on the WFP for prematurely taking a side.

When I asked why not a provisional “dual endorsement,” the various WFP staffers I spoke to didn’t dismiss the idea in principle — perhaps in part because they’ve entered day four of being pummeled by the left flank — but emphasized that it’s hard to direct volunteers to “one or another” campaign. Ultimately, they told me, the left needs to consolidate around one candidate. And their party picked Warren.

I don’t think we all need to get along; I don’t think it’s even clear who “we” are. (Many DSA members I’ve talked to in the past few days, for example, don’t really consider the WFP an ally or a peer.) Politically minded people — which is to say, activists, organizers, and the Very Online — tend to make political judgments early and stick to them. Bernie diehards, especially committed democratic socialists, are not suddenly going to become sympathetic to Elizabeth “Capitalist to My Bones” Warren. Disagreement, even uncivil disagreement, is not a sign of political peril. I don’t expect the tweet threads and Facebook rants to disappear or suddenly become uniformly cordial. There’s no kumbaya, my lord in the offing, and I wouldn’t push it if there was.

What everyone should do, however, is be clear-eyed about stakes and political realities. There will come a moment, god willing, in which Warren and Bernie supporters — from the WFP and the DSA — will have to throw down extremely hard for one candidate. For the sake of our mental health, and the effectiveness (if not the fraternity) of our future collaboration, we might try not to consistently impute only bad faith and nefarious motive to our political others.

It might even be possible to see the benefit of both candidates staying in the race, and of both having effective campaigns. Sanders is the second-choice pick of many Biden voters, whom he’ll hopefully continue to peel off. But former Hillary supporters now aligned with Buttigieg or Harris are not likely to warm to Sanders anytime soon.

Warren, however, unscathed by the battles of 2016 can and does attract these types, hastening the narrowing of the field and funneling the Democratic electorate into the two leftmost campaigns. If Warren and Sanders and their campaigns can retain the slightest degree of goodwill, when the time comes, it will be possible to consolidate a sturdy and mobilized progressive majority in the party, one that will not only defeat Trump, but sweep a slate of unapologetic left-wingers into office down ballot.

That is worth endorsing, early and often.