A paleolithic man crouches in the bushes, waiting for something to catch his attention. The tiniest movement kick-starts the bloodlust, that hard-wired desire to just fucking get it. He flings a projectile in its direction, an arrow or a spear maybe — weapons that create just the right amount of distance between his own body and that of his prey. This is important. If his aim is true, if the animal drops lifelessly to the ground, he will have accomplished two things: one, dinner. Two, and perhaps more important, he will have won.

Human history, or so conventional wisdom goes, is a story of violent, merciless competition. We have come to embrace the idea that a succession of one thing defeating another literally is history, whether that’s between species, political leaders, or conflicting ideologies. In our inherited notion of human history, our caveman — and he is always a man — comes home from a hard day on the plains with a wildebeest or a deer slung over his shoulder. His adoring cavewife and cavekids tuck into the prize around the campfire, as the winner recounts the tale of his courage and heroism. Just as significant as the prize, that hard-won carcass of meat, is the story. The drama. Many stories, told in chronological order, are what we call history (perhaps why, in German, the word for story and history are identical: Geschichte.)

This muddle of history and heroism has given us theories of Great Men, and a truly incomprehensible number of World War II documentaries, and also goes some way to explaining our current and insufficient appraisal of climate change. Capitalism, or so wrote Marx back in 1844, supposedly alienates us from four different things: from ourselves, from each other, from the products of our labor, and from nature. We develop an adversarial relationship with each. “Nature”(a constructed, slippery category that shifts over time) can, or even must, be tamed: capricious rivers are diverted, genomes are edited, crude oil is transformed into fuel.

The unpredictability brought on by climate change should, in theory, disrupt this thinking. The catastrophic repercussions of human activity, like melting glaciers and collapsing ecosystems, tell us that “nature” was never really “mastered” after all. Yet the same story persists: humans will win. We must. We always win. Not long ago, I saw a poster in central London, presumably put there by some university department, that said something like “Don’t worry. We’re on it” — the ‘it’ being the solution to climate change. The sheer hubris of some of the techno-fixes being bandied about with varying levels of seriousness, like sending a mirror the size of Greenland into space or pumping clouds of sulphur dioxide into the air, border on the dystopian. Conferences may have replaced the campfire, but the principle is basically the same: it’s the story, the legend, that matters.

Storytelling is a way of configuring and reconfiguring worlds; narratives can bring realities into being. I once took a writing workshop with someone who swore by power posing — the idea that adopting a wide stance with one’s arms raised quite literally invokes stature — and she would spend a minute before every reading “hacking” confidence into her body. With her arms above her head and her legs astride, she swore the technique changed her mentality and made her feel like she controlled the room. Without it, she claimed, she would be a gibbering, nervous wreck. However daft you might think power posing is, I was always impressed by her ability to slip fiction into the realm of the real.

Questioning the spear’s phallic, murderous logic, instead Le Guin tells the story of the carrier bag, the sling, the shell, or the gourd.

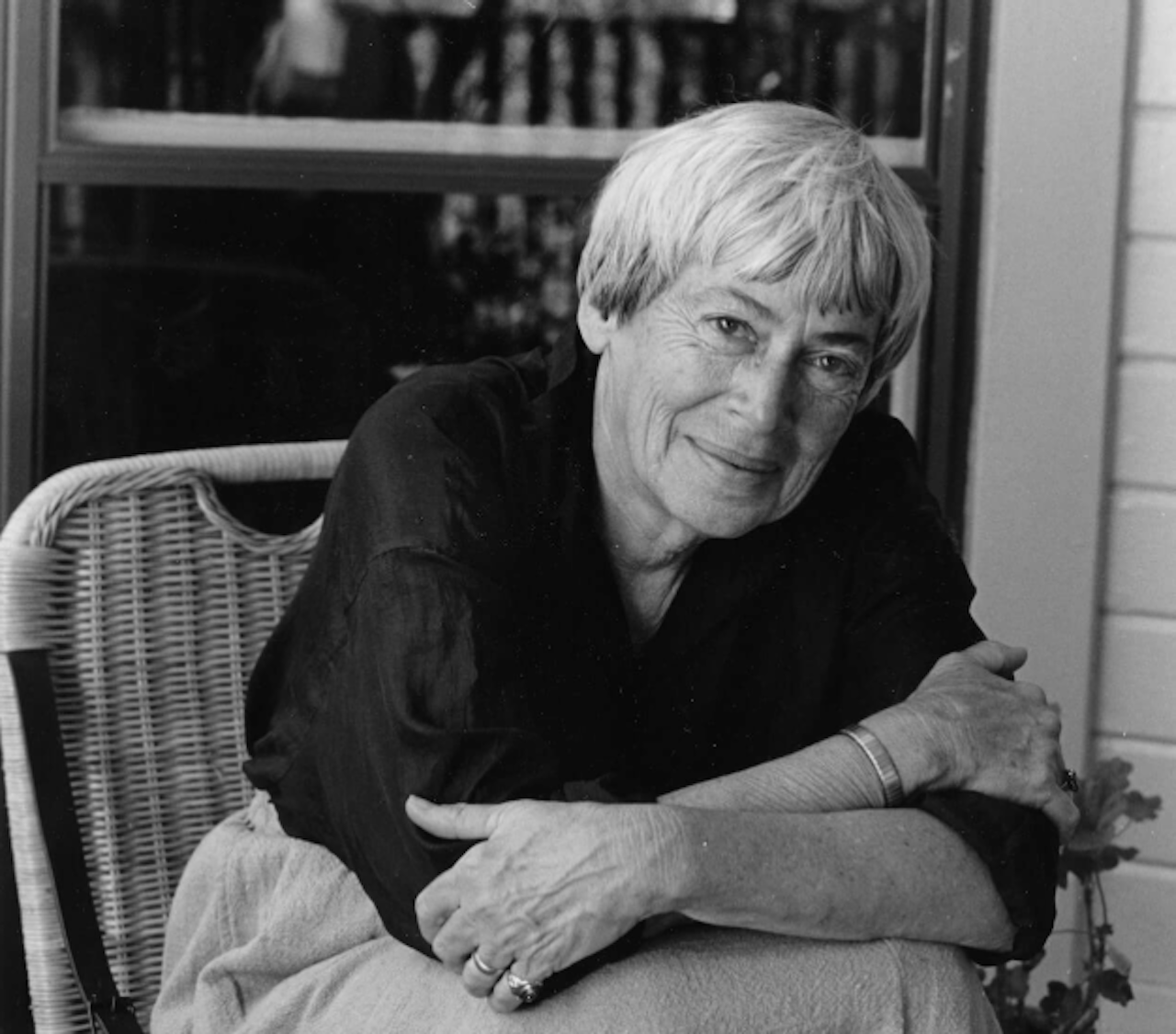

The generative potential of storytelling is especially pronounced in speculative fiction, a genre that mines our current reality as raw material for imaginary worldbuilding (this includes things like sci-fi, fantasy and horror). The genre’s patron saint, Ursula Le Guin, died last year aged 88, but she left behind her a breathtaking legacy of fiercely intelligent books and short stories imbued with her own anarcho-feminist, anticolonial politics. One of her best-known novels, The Dispossessed, imagines a small, separatist planet administered according to anarcho-syndicalist principles, what she subtitles an “ambiguous utopia” full of contradictions and complexity. On the planet Anarres, prison does not exist, work is voluntary, any claim to ownership is dismissed as “propertarian” — yet, despite all this, greed and power can still take hold. It feels like a book of thinking aloud, in which Le Guin is trying to figure out different realities through writing. It speaks to the kind of writer Le Guin was: generous and open minded, investigative and bursting with ideas, willing to be wrong, yet always reaching for a world free from harm.

“The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction,” an essay Le Guin wrote in 1986, disputes the idea that the spear was the earliest human tool, proposing that it was actually the receptacle. Questioning the spear’s phallic, murderous logic, instead Le Guin tells the story of the carrier bag, the sling, the shell, or the gourd. In this empty vessel, early humans could carry more than can be held in the hand and, therefore, gather food for later. Anyone who consistently forgets to bring their tote bag to the supermarket knows how significant this is. And besides, Le Guin writes, the idea that the spear came before the vessel doesn’t even make sense. “Sixty-five to eighty percent of what human beings ate in those regions in Paleolithic, Neolithic, and prehistoric times was gathered; only in the extreme Arctic was meat the staple food.”

Not only is the carrier bag theory plausible, it also does meaningful ideological work — shifting the way we look at humanity's foundations from a narrative of domination to one of gathering, holding, and sharing. Because I am, despite my best efforts, often soppy and sentimental, I sometimes imagine this like a really comforting group hug. But it’s not, really: the carrier bag holds things, sure, but it’s also messy and sometimes conflicted. Like when you’re trying to grab your sunglasses out of your bag, but those are stuck on your headphones, which are also tangled around your keys, and now the sunglasses have slipped into that hole in the lining.

Le Guin’s carrier bag is, in addition to a story about early humans, a method for storytelling itself, meaning it’s also a method of history. But unlike the spear (which follows a linear trajectory towards its target), and unlike the kind of linear way we’ve come to think of time and history in the West, the carrier bag is a big jumbled mess of stuff. One thing is entangled with another, and with another. Le Guin once described temporality in her Hainish Universe (a confederacy of human planets that feature in a number of her books) in the most delightfully psychedelic terms: “Any timeline for the books of Hainish descent would resemble the web of a spider on LSD.”

This lack of clear trajectory allowed Le Guin to test out all kinds of political eventualities, without the need to tie everything neatly together. It makes room for complexity and contradiction, for difference and simultaneity. This, I think, is a pretty radical way of looking at the world, one that departs from the idea of history as a long line of victories. Le Guin describes her discovery of the carrier bag theory as grounding her “in human culture in a way I never felt grounded before.” The stick, sword, or spear, designed for “bashing and killing,” alienated her from history so much that she felt she “was either extremely defective as a human being, or not human at all.”

The only problem is that a carrier bag story isn’t, at first glance, very exciting. “It is hard to tell”, writes Le Guin, “a really gripping tale of how I wrested a wild-oat seed from its husk, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then I scratched my gnat bites, and Ool said something funny, and we went to the creek and got a drink and watched newts for a while, and then I found another patch of oats…”

As well as its meandering narrative, a carrier bag story also contains no heroes. There are, instead, many different protagonists with equal importance to the plot. This is a very difficult way to tell a story, fictional or otherwise. While, in reality, most meaningful social change is the result of collective action, we aren’t very good at recounting such a diffusely distributed account. The meetings, the fundraising, the careful and drawn-out negotiations — they’re so boring! Who wants to watch a movie about a four-hour meeting between community stakeholders?

The introduction of a singular hero, however, replicates a very specific and historical power relation. The pioneers and the saviors: likely male, likely white, almost certainly brimming with unearned confidence. The veneration of the hero reduces others into victims: those who must be rescued. “The prototypical savior is a person who has been raised in privilege and taught implicitly or explicitly (or both) that they possess the answers and skills needed to rescue others,” writes Jordan Flaherty in his book No More Heroes. To be a hero is fundamentally privileged, and any act of heroism reinforces that privilege.

The carrier bag story, with its lack of heroes, is a collective rather than individualist endeavor. It’s this that differentiates the carrier bag from Walter Benjamin’s “ragpicker,” an emblematic modernist figure who “early in the morning, bad tempered and a tad tipsy, spears remnants of discourse and fragments of language with his stick and throws them, grumbling, into his cart.” Engaged in endless bricolage, the ragpicker is a serial appropriator — it’s John Cage taking the Balinese gamelan as his own, it’s Picasso’s “primitivism.” The carrier bag gatherer, meanwhile, is no lone genius (genius being its own kind of heroism, after all), but rather someone rooted in a shared existence.

We will not “beat” climate change, nor is “nature” our adversary. If the planet could be considered a container for all life, in which everything — plants, animals, humans — are all held together, then to attempt domination becomes a self-defeating act. By letting ourselves “become part of the killer story,” writes Le Guin, “we may get finished along with it.” All of which is to say: we have to abandon the old story.

The social theorist Donna Haraway, who has been deeply influenced by Le Guin’s writings, implores us to tell other stories about this weird shared reality: “It matters what stories tell stories,” she writes. “It matters what worlds world worlds.” We are still learning how to tell stories about climate change. It is fundamentally a more-than-human problem, one that simultaneously affects all communities of people, animals, plants — albeit asymmetrically. The kind of story we need right now is unheroic, incorporating social movements, political imagination and nonhuman actors. In this story, time doesn’t progress in an easily digestible straight line, with a beginning, middle and end. Instead there are many timelines, each darting around, bringing actions of the past and future into the present. It collapses nature as a category, recognizing that we’re already a part of it. In a climate change story, nobody will win, but if we learn to tell it differently more of us can survive.