but this place is just right.

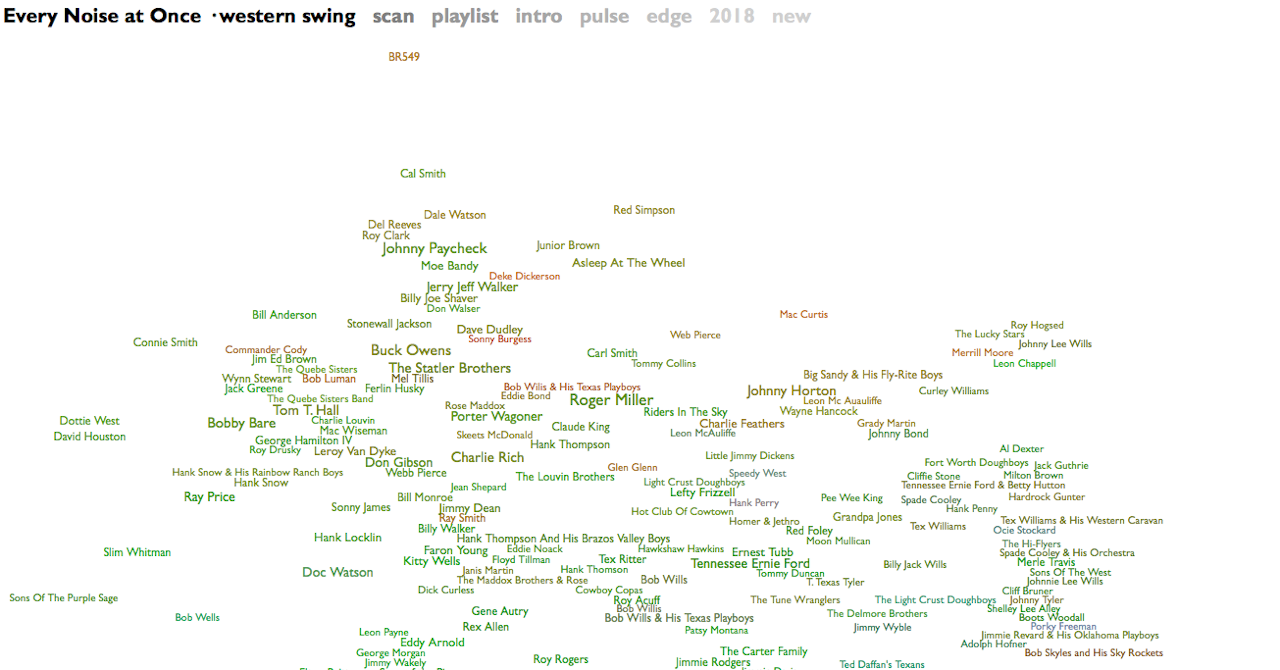

You could argue that on the face of it, the project Every Noise At Once feels like staring into the abyss, and that the abyss is a completely straight line. The site, designed by Glenn McDonald, is an effort to visually map all the world’s musical genres algorithmically using Spotify data. Through the miracle of computer programming, the collective artistic genius and work of diverse individuals and cultures is flattened out into a single sprawling word cloud, with rock genres cluttering in the center, and other more remote musics pulsing off in seemingly stochastic drifts. Some might view it as a sign of impending doom, I suppose. But you could also see it as beautiful, fractal representation of the joys to be had in crossing cultures and musical styles; a vision of a world with the walls taken out.

Towards the top (more electronic sounds) and the right (spikier, faster noises) you can listen to genres like jumptek (fast-paced techno), groove room (retro ’80selectronic dance) and deep melodic euro house (pretty much what it says it is). Down at the bottom (organic sounds) and the left (atmospheric) there’s Korean contemporary classical and Austro-Geman modernism. You can click on any name to hear a 30-second sample. Tapping the arrow at the right of each name allows you to dive deeper to see a map of all the artists associated with the genre of, say, veena, which is defined by its use of an Indian classical lute-like stringed instrument. With another click you can generate a Spotify playlist to introduce you to the genre or its most popular performers.

Again, Every Noise at Once’s genre designations are algorithmically generated — and no algorithm is perfect. As a longtime fan of Western Swing, I was somewhat horrified to find that its cloud map is centered not on the King of Western Swing himself, Bob Wills, but on performers like Lefty Frizzell, Charlie Rich, and Doc Watson, who are neither western nor swing. Who let all these southeastern hayseeds into our big band bash? Take it away, Leon!

But after the initial bout of shaking my fist at the computer and lamenting the erasure of the Texas Playboys, I’ll admit I found the confusion endearing. McDonald is cheerfully upfront about the fact that Every Noise At Once isn’t a definitive single view of the world of music, but a discussion about possible landscapes. “Our computers can now enter plausibly into arguments over almost 500 genres, from a cappella to zydeco,” he says in an explanation of the project. Genres are always fuzzy, porous, and changeable anyway. Every Noise at Once updates and rearranges itself regularly, offering not a single vision of global sound, but a more tentative invitation to explore outside of your comfort zone.

And exploring is really a blast. It’s great fun to scroll around the map, looking for genres you’ve never heard of, and taking a moment to try to figure out what it is, where it’s from, and what it sounds like. I first found the site when researching lowercase — an ambient genre which is almost indistinguishable from silence. Most recently, I stumbled on chutney, a genre located somewhat inexplicably next to progressive bluegrass. It turned out to be frenetic percussive Caribbean party music.

A quick trip to Wikipedia (Every Noise At Once prompts a lot of quick trips to Wikipedia) tells you that chutney is indeed a genre based in the southern Caribbean, especially Trinidad and Tobago, which was most popular in the 1980s. It’s a style that incorporates elements of Indian music into amped-up calyps, which might explain why it’s close to amped up bluegrass on the map,

The largest name (indicating the most popular artist) on the chutney screen is Machel Montano. According to a quick visit to Youtube (Every Noise at Once prompts a lot of quick trips to YouTube) he just released a collaboration with Ashanti. “Travel all over the globe/Wherever you go I’ll go,” she sings. I’d thought I was off my personal map, but to no one’s real surprise, American pop stars had gotten there before me.

Finding things you know nothing about is definitely part of the joy of Every Noise At Once. But the shock of recognition when I discovered Ashanti, one of my favorite performers from the early 2000s, had ties to a genre that was heretofore unknown to me, is also part of the pleasure. If you’re a music obsessive, or even if you’re not, Every Noise At Once probably includes many noises you’ve heard before.

Waita maori, for example, mostly features Maori pop ballads, which sound a good bit like pop ballads sung in other languages. Música de fondo, or background music, is just a Spanish term for ambient music. The genre of Ghazal according to Wikipedia, refers to a style of Arabic love poetry which became popular in Pakistan and South Asia. The Every Noise At Once genre map includes some classical ghazal performers like Ahmed Hussein, but it also includes a lot of Bollywood singers and composers whose presence, I suspect, is as incongruous as Doc Watson popping up in Western Swing. For me, at least, browsing the site’s genres can feel like wandering through a new city with houses I’ve seen before. And that was even before I clicked on the artist Junoon, whose sound clip is a stinging classic rock guitar solo. (They are, Wikipedia tells me, a Sufi rock band.)

The reason music genres are hard to define is that music doesn’t have borders; everybody listens to everybody else. Ashanti grooves out to Machel Montano; Junoon loves Led Zeppelin; M.I.A. listened to Brazilian funk carioca, and Charlie Parker was a fan of country. Humans have always loved talking to each other. New technology just makes it easier to get in touch.

The term “globalization” tends to get a bad rap. It’s one of the go-to boogeymen for people of all political persuasions looking to blame the results of 30 or so years of rapid social and economic change on… something. Regardless of its merit, those who deride it love to tell us that globalization is a blight, and that without a sharp distinction between here and there, individuality, jobs and pride all leak away. But in its own subtle, valiant way, Every Noise at Once stands in refutation of that argument.

One of the most amazing things about the web is that it’s made so much information, and so much music, instantly available to so many people. That’s not a new insight, but swimming around in Every Noise at Once really makes you recognize what a vast, amazing sea of knowledge and art we're all swimming in. Bob Wills, Asha Bhosle, Yoshikazu Mera, the Kilimanjaro Darkjazz Ensemble, and various other humans, living and dead, all took noises out and put them back in to this one enormous, amorphous, unboundable project. That project is a lot bigger than Every Noise At Once, but Every Noise at Once reminds you that it’s one worth appreciating.