No legally permitted public display inspires me with more secondhand embarrassment than a real live human being wearing a T-shirt with a threat printed on it. Needlessly aggressive T-shirt slogans have been around for decades, but the computer nerd condescension and sassy bootleg cartoon characters of yesteryear are being outpaced by something more overtly antisocial.

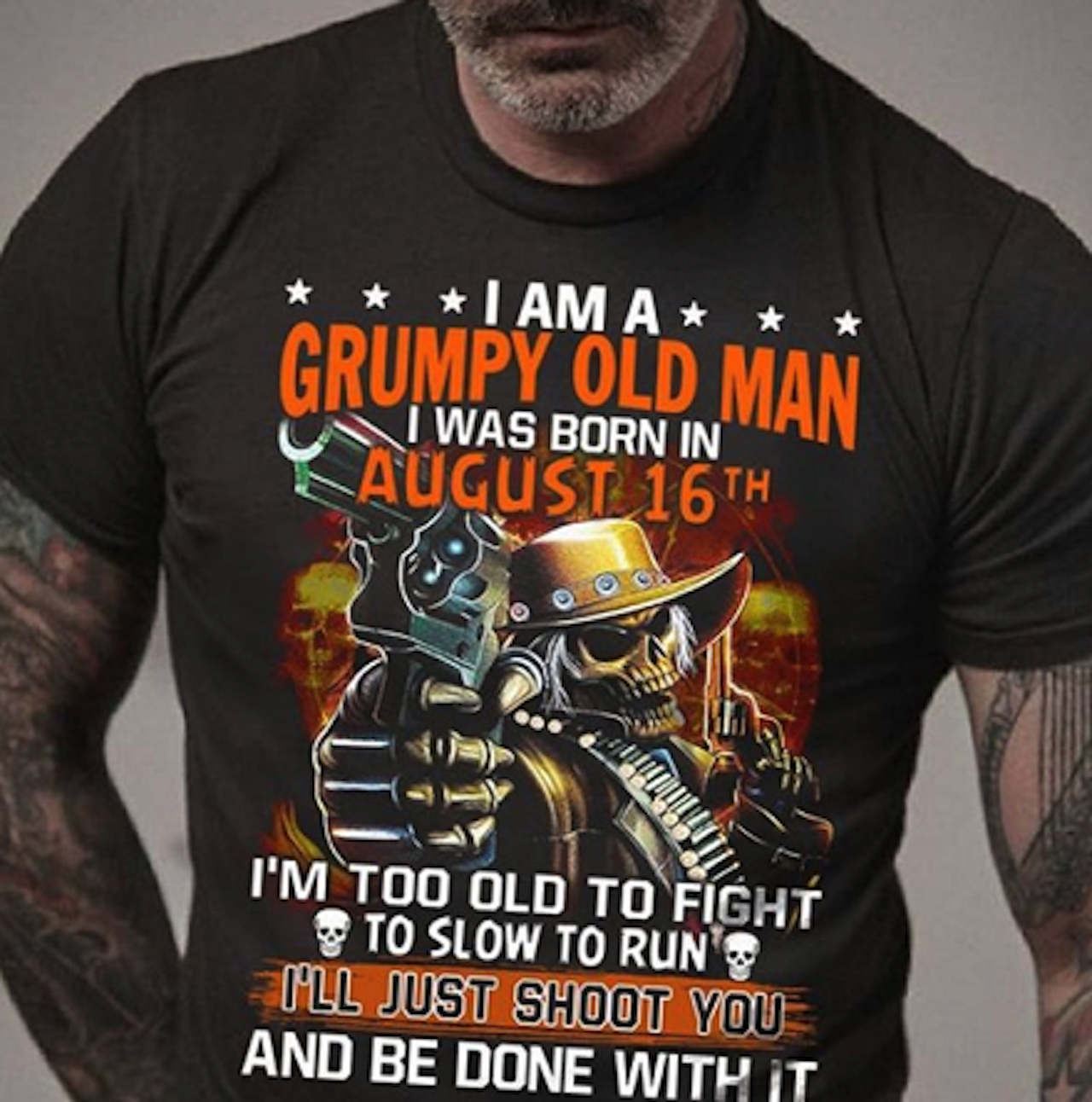

In these late 2010s, a new shirt format is all the rage with the kind of person who wants strangers to stare at their torso. This new variety uses identifiers scrubbed from our Facebook data, like “born in January” or “nursing assistant” or “loves java” in order to sell us auto-generated merchandise targeted to us as an individual. This by itself almost seems tame, given that the use of our data by advertisers has been normalized by our powerlessness to stop it. But what these targeted shirts do with mundane personal details is thoroughly disarming. Either through algorithmic creep or genuine customer interest, targeted clothes have morphed into statements of antisociality that treat being born on a certain day, working a certain job, or having a tattooed daughter as valid reasons for developing a violent siege mentality.

The Instagram account @facebookshirts and the Reddit community /r/targetedshirts have cataloged hundreds of examples. Posts alternate between screenshots of Facebook advertisements, not yet printed on cotton, and photographs of real people. The juxtaposition is jarring; in an instant, what seems like it could only exist in a screenshot can become a real shirt someone paid for. There are endless pictures of people standing in line, walking down the sidewalk and eating at restaurants while wearing shirts that say things like “I was born in December. If you don’t like it BACK THE FUCK UP” or “Never underestimate a woman who listens to Avenged Sevenfold and was born in October.” The most charitable reading would be that these shirts were gifts, but then they would contain the personal info of the purchaser rather than the recipient.

The thought process behind the purchase of one of these ultra-specific shirts is hard to fathom. At first there must be a sense of discovery. Oh, I was born in January. How did this Facebook advertiser know? Ideally, that question should be answerable through basic deduction, but for the transaction to work, it must remain shrouded in mystery. Then, there must be some sense, entirely removed from the realm of astrology, that the month of one’s birth imbues one with certain characteristics that would theoretically lend themselves to murdering people who read the shirt. I do feel like, if a February person came at me, in a self-defense situation, I could behead them pretty easily.

Then, presumably, the customer scans once more over the part with the skull and crossbones that threatens the reader “they’ll never find your body,” determines that this is an entirely normal thing to pair with the information that you were born in January, and drops the $24.99. It defies explanation. It’s as if birthstones only came embedded in brass knuckles, historically, and no one was able to figure out why everyone was so willing to fight each other over the date their parents decided to have sex plus nine months.

This most recent graphic T-shirt trend is not without precedent. The graphic tee came into ubiquity in the 1960s with an array of simple corporate designs still sold at Target: the Coca-Cola logo, the Rolling Stones tongue. The only real angry shirts of the period were worn by activists, who, though justified in their rage at an unequal system, had the foresight to stick with concise slogans like “BLACK POWER” rather than “Don’t talk to me before I have my coffee. I am a bomb-maker for the Weather Underground.” By the late 1970s, statement T-shirts with large block text and confused messages were all the rage. The English fashion designer Katherine Hamnett was responsible for both “CHOOSE LIFE,” which was intended as a generic anti-war message but was co-opted by the anti-abortion movement, and, indirectly, “FRANKIE SAYS RELAX.”

#bootlegbart Courtesy of @round2hollywood#bartsimspon#thesimpsons#90stshirt#bootleg#blackbartpic.twitter.com/AoPUrYIHlK

— Bootleg Bart (@bootlegbart) October 11, 2018

By the 1990s, people started wearing shirts that were more playful and mischievous. Many of these shirts happened to feature Bart Simpson, the rebellious attitude of whom opened up a whole new world for screen printers. Suddenly, America’s favorite 10-year-old was taking a stand against AIDS, giving daps to Nelson Mandela, and kicking Saddam Hussein’s ass. The account @bootlegbart, which was banned from Instagram by the fascists at 21st Century Fox and is now only available on Twitter, has been archiving such shirts since 2012. The raw number of Bart shirts printed between 1990 and 1995 implies there was a cultural niche that needed filling; Americans badly wanted a sassy, irreverent cartoon character to voice their innermost desires.

In the mid-1990s, as Bartmania was waning, Big Dogs Sportswear figured out how to replicate the generic sassiness of decontextualized Bart without infringing on a Fox trademark. The answer was a big cartoon dog crossing his arms and saying things like “I wish people were more fluent in SHUTTING UP” and “Don’t like my attitude? Take a number.” In 1997, the same year Big Dogs had its IPO, The Simpsons used the one-off character Poochie, a surfing dog with attitude cynically crafted by marketing executives, to satirize the post-Bart proliferation of arm-crossing focus-grouped cartoon mascots.

After 9/11, the T-shirt market got more complicated. Wearing a patriotic shirt was a national duty, and tonally they became much more serious. The playfulness of Bart Simpson mooning Saddam Hussein or Muammar Gaddafi disappeared; I can find no evidence of any shirt that featured Bart disrespecting Osama bin Laden. (The dearth of Bart shirts in general during the 2000s can be explained by The Simpsons getting bad around 1999 or so, but also by the rise of juvenile skate-punk bands and MTV pranksters who replicated Bart’s irreverence in a new, more lucrative context.)

In the waning aughts, the internet opened new niches for needlessly aggressive T-shirts. Sites like the recently shuttered ThinkGeek clad every antisocial 14-year-old in America in now-classic designs like “No I will not fix your computer” and ��Genius at work.” ThinkGeek’s evil twin was the heavily-advertised TShirtHell.com, which is still online and still formatted for an 800 x 600 monitor. T-Shirt Hell, like Tucker Max, was for the edgiest 2000s kids only. It takes real guts to wear a shirt that says “Shittles: Taste the Asshole” or “Fuck you and your non-offensive T-shirt” out in public, and people did.

Edgy shirts in the late 2000s maintained much of the forced offensiveness of their predecessors, but the ascendant meme culture was slowly creeping in. The “Cool story, bro” shirt, and its variant “Cool story babe, now make me a sandwich,” were ubiquitous for several years despite our best efforts. The internet’s flirtation with “Three Wolf Moon,” a kitschy shirt design co-opted by what people in 2010 called “hipsters,” increased the ties between social media and zero-irony shirts with badass wolves on them, setting the stage for what would happen next.

The algorithm absorbed the angry-shirt-marketing-complex like an amoeba. Around 2014, people start seeing targeted shirts using basic information, like “It’s a Smith thing, you wouldn’t understand.” Selling such shirts is undoubtedly easy. Facebook gives advertisers the tools to target demographics as specific as a certain name or birthday, and there are dozens of Cafepress-style websites willing to do one-off shirt orders and give the “designer” a cut.

The speed at which these shirts have become more threatening is apparent from articles only a few years old. A 2014 Mashable listicle of the “creepiest targeted Facebook ads” opens with a shirt that reads “Keep calm and let Cameron handle it.” A year later, a 2015 Gizmodo article addressed the targeted shirt slogan “Living in Singapore with American roots.” Sometime between then and 2018, when a Vice News Tonight segment featured a shirt with a hooded skeleton pointing two revolvers at the viewer in defense of his being a “SEPTEMBER GUY,” the guns and violent threats were added.

Why did the stakes become so high so quickly, as if a pogrom was launched against September Guys or January Guys that brought back a long-suppressed tribal instinct? What happened? The frustrating thing about any phenomenon driven primarily by the almighty algorithm is that only the algorithm will ever know why it does what it does. We just get to watch and wonder, slowly gaining the subconscious urge to communicate to those around us that we are MILLENNIALS reading this ARTICLE on The Outline DOT COM.