Once inside the new glass pavilion of the Royal Museum of Central Africa, visitors pass the gift shop, reception areas, and overhead restaurant, leave their coats in the free lockers, and then descend into a long white hallway.

The new building, just outside Brussels, is the centerpiece of a renovation that took five years and cost more than $80 million. Museum officials said it would double the exhibition space and, for the first time, confront Belgium’s occupation of Central Africa. One of history’s most extreme examples of colonialism, the reign spanned 70 years, from 1890 to 1960, and killed half the population of an area known today as the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Painted at the end of the long white hall are these words:

EVERYTHING PASSES, EXCEPT THE PAST

It’s in four languages on the wall above a pirogue, a humongous black canoe, hand-hewn from the 100-foot trunk of a Sepo tree. Farther down, just before stairs ascend into a dim room, is a display card in four languages. They read:

In 1957, the former King Leopold III made a tour through the Congo. In the city of Ubundu, he undertook a trip across the river in this pirogue . . . the inhabitants of Ubundu made the pirogue on their own initiative, as a gift for the former monarch. The question remains whether it was in fact commissioned by the colonial administration.

This first encounter sets the tone of the new museum very well. Both visually impressive and calculatedly confusing, something else lies within this stellar space, with its dance studios, some 10,000 musical instruments, and an academically affiliated science center. It took a while to realize what that something is; it’s hard to see what’s not there.

The museum was opened in 1910 by King Leopold II and offered nothing critical about the occupation until 2005. It closed in 2013 for the aforementioned renovation, and then reopened amid protests in December 2018. Positive reviews followed: “Belgium is confronting a legacy of colonialism and racism,” said NPR. “Museum Reopens to Confront its Colonial Demons,” read Reuters.

There were others, all with the same absent-present tone so ubiquitous in internet news posts, that authoritative tone the author takes when they want to sound like they were there but not there.

I went there a month later, and spent two days trying to access its famed music archives, and mostly just looking around. And at the risk of spoiling any big, revelatory climax, I’ll just tell you: there’s basically nothing in the museum that honestly confronts what went on in Central Africa.

That this discovery defeats the museum’s successfully advertised purpose was the original hook for this article. Two days in this information-starved setting changed things, however, because it turns out that this regal building, everything in it, and especially everything not in it, speak a greater and more terrible truth than any bureaucrat or diorama ever could— that Belgium can’t confront its own evil.

This is understandable. As with Americans and slavery, it’s not a topic people here are happy to talk about. Plus, there’s only so much to say about atrocity.

One reason Leopold’s reign was so atrocious may be because he was such an atrocious person. Even among the echelons of European royalty, he remains hard to beat. Léopold-Louis-Philippe-Marie-Victor was a dumb and awkward military kid, who, as an adult, still wore his saber. He disliked art, music, reading, and theatre, but loved statues of himself and also lavish palaces, and the attention they provided. Some of his mistresses were children, and one monthly bill for one brothel that specialized in sex traffic equaled $130,000 (all historical figures in this article have been adjusted). He also always needed money, and by the time he was crowned, colonizing places with rich natural resources was more profitable than the dwindling slave trade.

(By the way: Slavery pre-made the Congo a likely target for colonization. The slave ports here date back to the 15th century, when the king, called the ManiKongo, first met a group of Portuguese traders at the mouth of his great river in 1491. Leopold had no interest in trading, of course, so everything taken from the Congo was in fact stolen, including most of the stuff that’s in the museum today. The Democratic Republic of the Congo has since asked for its stuff back, and protests over this are a probable reason the Belgian king didn’t attend the opening last December.)

The Congolese still had almost no written language when Belgian troops began moving inland 400 years later, and since almost no written records survive, estimates vary when it comes to the occupation. Per average estimates, Leopold extracted $1 billion from the Congo and killed 10 million people doing it.

With missionarial claims about spreading democracy, the first troops arrived in 1888, and soon Leopold christened his new colony, the Congo Free State. (He would never visit.) At almost 1 million square miles, it was 1/13th of the continent and 75 times the size of Belgium. And it was his: The land and everyone/thing in it, he said, belonged not to the state, but to him.

The U.S. and other power centers recognized this arrangement, and excavation began. Leopold wanted to quickly move natural resources like ivory and rubber downriver to port in Boma, at the Atlantic’s eastern edge, and ordered a train be built that followed the treacherous waterway into the country’s heart. Draft horses died in the hot climate, which meant carrying industrial equipment through 200 miles of jungle, which meant that the Belgians needed porters. These were the first enslaved Congolese, who at the time had only spears and clubs to fight their ghostly invaders, who had machine guns.

Soon, some 60,000 Congolese were put to work porting, digging, blasting, and building a railroad that took almost 10 years to finish. The workforce was “all ages and both sexes,” according to one dissenter. People died of murder, disease, starvation, work-to-deathness, infection from the iron chains that had replaced wooden yolks, and from prolonged whippings with something called a chiccote, a twisted length of hippo flesh resembling a long purple corkscrew.

There’s basically nothing in the museum that honestly confronts what went on in Central Africa.

Leopold’s death squad was called Force Publique, and consisted of unsuccessful Belgians from various economic brackets. They were savagely controlling. The hands of the uncooperative and infected children were hacked off and smoked, then saved as proof for visiting officers and/or exchanged for currency. (William Sheppard, a missionary-turned -activist, once testified seeing 81 hands smoking over a bonfire.)

Force Publique was run by a guy named Léon Rom. And while Leopold’s behavior was formal and removed, Rom’s behavior was flamboyantly hands-on. (His penchant for public torture and beheadings was noted by a young apprentice named Konrad Korzeniowski, who went up river in 1890 and nine years later published the novella Heart of Darkness under the name Joseph Conrad.) Rom’s behavior seemingly had a mutatious trickle-down effect, because once his officers were turned loose in the field, they went berserk. In one village, an officer fed his dog its own tail. Another cut off a girl’s foot and sent it to her father. Another made young men rape their mothers.

Still, all referred to Leopold as “King of the Beasts.”

The king got crazier as he got richer. And greedier, renovating his palaces, importing African animals to cold Belgium, and then, in 1897 installing a human zoo at his country estate for the nearby world’s fair. It had huts, a fake lake, and 267 enslaved Congolese (visitors threw them bananas). He hated and then disowned his children, and eventually installed a teenage mistress next to the royal palace. Every morning he would wake, strap on his saber, consume a jar of marmalade, and then ride a big tricycle over to her carriage house. When he was 68, she gave birth to a boy with a deformed hand.

The money poured into Belgium, but eventually word got out. Former soldiers with what’s now known as PTSD started to talk — eventually to press — and after ghastly photographic evidence surfaced, wealthy white people started to organize, forming a Commission of Inquiry, the members of which included a judge. In 1904 the Commission visited Africa and took the testimonies of 370 Congolese.

“When I was very small, the soldiers came to make war in my village,” said M’Putila of Bokote. “A soldier used a knife to cut off my right hand and took it away. I saw that he was carrying other cut-off hands.”

“Look at the scars all over my body,” said a man named Lilongo, who was tied to a tree. “We were hanging in this way for several days.”

“Twice, the sentries, to punish me, pulled up my skirt and put clay in my vagina,” said Mingo of Mampoko. “This made me suffer greatly.”

Leopold denied everything, and was so good at misinformation and underminement that it worked for a while. (Congolese testimonies survived, but were locked in government archives until 1980 and labeled “No Access For Researchers.”) But the truth had surfaced, and in 1908, in a typically crooked business transaction, he formally sold his deeply indebted colony to the Belgian government. It took eight days to burn the records. He told a confidant: “They have no right to know what I did there.”

Belgium ruled the Congo for another 50 years, controlling citizens with the Force Publique and a sharecropper-esque system of debt. The tide turned after a final bloody protest in 1959, and the Belgian king granted the Congo independence. “It is now up to you, gentleman,” he said. “To show that you are worthy of our confidence.”

The people democratically elected a prime minister named Patrice Lumumba, an event that quickly gained U.S. attention, since the new democracy could jeopardize tire prices. President Eisenhower reportedly told his C.I.A. director that Lumumba should be eliminated. Two months later, he was arrested, tortured, executed, then dismembered and dissolved in acid. In 1965, with the help of President Kennedy and the Air Force, a dictator named Mobutu took power. He ruled much the way Leopold did, and for about as long. An infrequent White House guest, the first President Bush called him “one of our most valued friends.”

Nothing you just read about was acknowledged at the Royal Museum of Central Africa for almost a century.

Then, in 2005, an exhibit called “Memory of Congo: The Colonial Era” opened to positive reviews. It closed as planned after eight months but one of the people who went there and saw it was Adam Hochschild, a Berkeley professor and the author of King Leopold’s Ghost, an unblinking history of the whole depraved disaster in the Congo and the main information source for this article.

In one village, an officer fed his dog its own tail. Another cut off a girl’s foot and sent it to her father.

Life-size images of Congolese musicians, Hochschild noted, stood next to cases with small photos from Leopold’s reign. One photo of an assembly, was captioned “Conference of Inquiry,” with no relevant details. Four were atrocity photos, blended in with non-atrocity photos. To coincide with the exhibit, the museum published a book with Congolese art, farming information, and almost 40 scholarly articles, none of which mentioned hostages or slave labor. “Both exhibit and book were examples of how to pretend to acknowledge something without really doing so,” wrote Hochschild, who covered the opening. “This does not leave me optimistic about seeing the Congo’s history fully portrayed by the Royal Museum in the future.”

The museum closed in 2013 for renovations and reopened this December.

The museum is more of a museum about Africa, and in fact it boasts “one of the largest collections of Africana” in the world. And it’s nice in that formally extreme European way, with long sharp hedges and vantage points that unfold as soo)n as you round a corner or turn up the long drive, facing a fake lake that reflects a stately main building that resembles the Lincoln Memorial. The campus consists of the adjoined new and old buildings, the king’s old mansion, and the archive, a long, cement-y thing with no discernable entrance and a lobby like the lobby in the building where Alex lives in A Clockwork Orange.

I never got access to the archives. None of the people I emailed or met at the three different offices inside the archive building had access, they said. The 38,000 recordings are now all digital, but the music person wasn’t there. A week later he sent me a link that didn’t work, because, he responded, they’re only accessible on the museum’s computers.

One reason Leopold’s reign was so atrocious may be because he was such an atrocious person.

This could have been executive order or just collective guarded behavior. Whatever it was, it was evident all the way to the top, though at the top was something wholly different, something I cannot even quite describe. The exchange I had with the director hopefully speaks for itself, though I’m not sure any quotes could capture sort of aggressive not-caringness he displayed.

An agricultural economist by trade, Dr. Guido Gryseels has been the museum’s director since 2001 and oversees a staff of 275. His office is in the old king’s mansion, where we met for 20 minutes at a table set with coffee, teas, and sparkling waters. He wore a suit, tie, and untucked shirt, and was late, he explained, because he had come from a reception at the royal palace. He talked for 10 minutes about the research archives, children’s workshops, and the 75,000 new visitors’ response.

“They think it’s absolutely fantastic,” he said. “I get nothing but positive feedback.”

Then he stood up, walked out, and spoke to his secretary in Dutch.

Colonialism was “racist and authoritarian,” he said upon returning. “A system we can only consider as immoral.”

Then he got up and left again.

He returned, and I asked about something he’d said about the 2005 pop-up exhibit, how it “gave a comprehensive view of the colonization both in positive aspects and very critical aspects.”

“We don’t like talking about positive aspects,” he answered. “It’s a little bit like, a woman gets raped with a lot of violence, and afterwards you would say, ‘Hey, it gave you a nice baby.’ You know?”

He added that in 1960, Congo had the same GNP as Canada.

“That was one of the richest countries in the world. Well now it’s one of the poorest,” he said. “Obviously it gives you a lot of food for thought.”

Regarding the return of artifacts to the Congo, he said. “We’re talking about it.”

“We’re trying to give a very balanced view,” he concluded. “I’m very happy.”

There’s about a dozen prominent pieces of modern Congolese art situated throughout the museum, works you may have seen around the internet. These works are abstract, not explicit. There’s also televisions in some corners, where you can watch old film or a social science academic talk about the cultural implications of what went on. Here and there are empty display cases or unfinished rooms, with a lot of reminders about things being in progress, still. There’s one flat case with four whips, but they’re mixed in with stacked books and a mask, and only one of the whips is a chiccote.

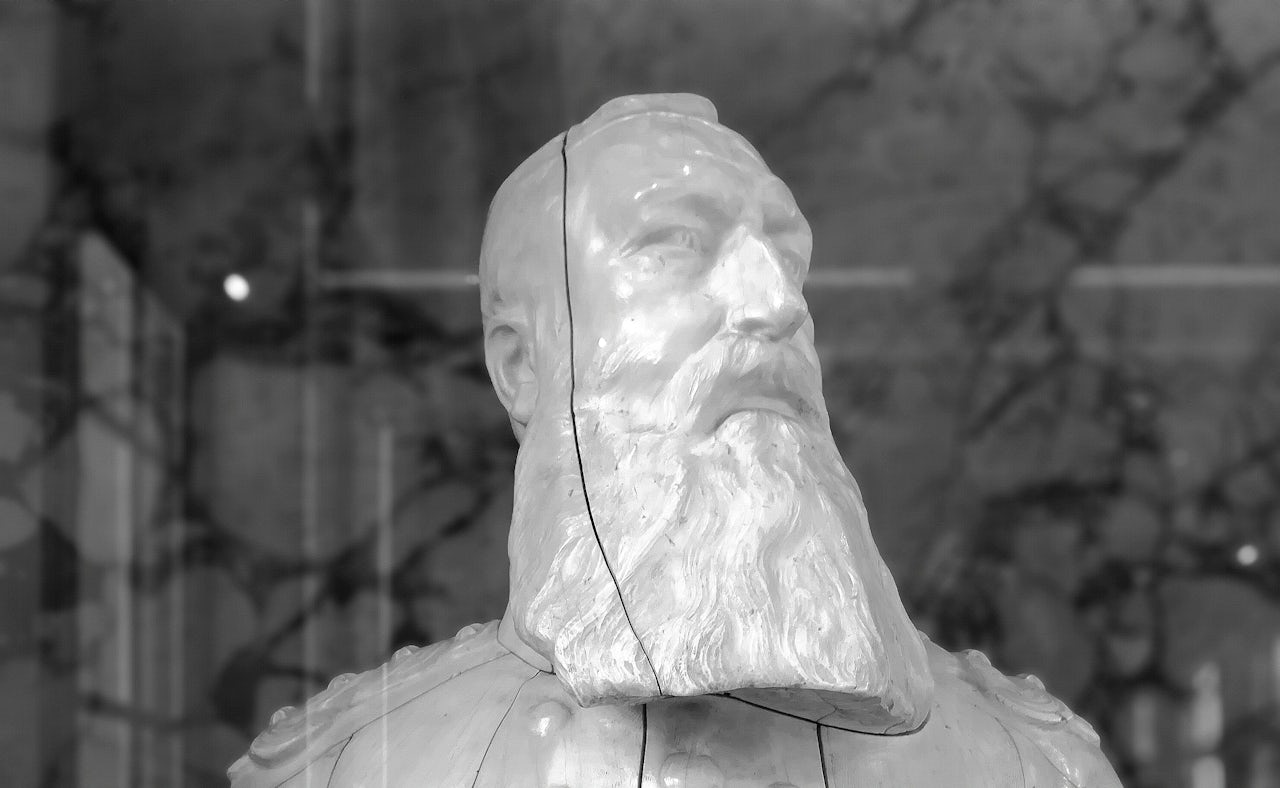

There’s big, sometimes hands-on dioramas where you can play drums, watch movies on African farming, or push a big button and hear Congolese rhumba, the music of the Independence. There’s a long nature-themed room with stuffed elephants and a hippo that feels more like a trophy room. There is little about Leopold, though one side display, an ivory bust standing among some tusks, should either be destroyed or moved back to the main entrance, among tall stacks of Hochschild’s book and giant prints of atrocity photos, since there is not one photo of hands hacked-off, or of a child with hacked-off hands.

There is one case with chains and collars, but they turn out to be from the slave-trade era. The seven-sentence label reads: “In 2001, the UN recognizes slavery and the slave trade as a crime against humanity,” and, “The slave trade leads to depopulation, refugee flows, political destabilization, and the banality of violence.”

There is a case dedicated to the human zoo. It’s in a dim room, with photographs of huts or trees, and none of bars or chains. The old ID cards at the bottom of the display, dense with titles like “Unidentified” or “Village Congolese” followed by long index codes.

Outside, where the human zoo stood, there is reportedly a plaque, but I couldn’t find it.