Late last month, Samantha Kuhr called 911 in a frenzy — she'd just checked the Ring doorbell camera installed at her Hermosa Beach, CA home and seen a strange man walk through her front door. She begged them to send help, sure that she was in danger, until the dispatcher asked her to check the timestamp on the video. According to Ring, the intruder had entered 20 minutes ago. So he had been in the house for nearly a half-hour without being noticed?

It took Kuhr a moment to realize that the man in the security footage was her, and that she had called the cops on herself. Embarrassed, she instead asked that they not blacklist her for misusing 911.

This is just one of dozens of stories about how Ring, a home and neighborhood security suite that’s seen a boom in popularity this past year, and similar services are likely doing more to make neighborhoods paranoid rather than safe.

In 2016, Jamie Siminoff, the CEO of the surveillance-doorbell company Ring, sent an internal email stating the company was “going to war with anyone who wants to harm a neighborhood.”

Ring cameras and doorbells, which allow homeowners to see and take video of anyone who comes to their front door, have been on the market since 2013, when the product was buoyed by an appearance on Shark Tank. But it's only been since Amazon last year purchased the company for more than $1.2 billion that its devices, which start at $99, have become suburban mainstays; it also recently launched a neighborhood watch app that “makes home security a social thing,” according to CNET.

After all, Ring doesn't sell doorbells — it sells omnipotence (incredibly ironic, given its parent company Amazon's business is using everything it knows about its customers to advertise at them). Just consider their commercials, where bumbling burglars can't take a single step onto someone's lawn without being spotted and scared off. A Ring Video Doorbell with connected Ring Floodlight Cams (a combo that will run you about $350) allows customers to think of themselves as domestic gods, able to see and eliminate all possible threats with the click of a button. The related neighborhood watch app, Neighbors, lets everyone in town share their video feeds, turning the neighborhood into a surveillable fortress.

Ring, alongside other popular neighborhood watch apps like Nextdoor and the live-crime reporting app Citizen, market themselves as the key to keeping ourselves safe in a dangerous society. These apps all work through a similar system. The user provides their address and other personal data, joins a group with people living near them, and receives constant updates about what's going on around them. On Ring and Nextdoor, these updates are posted by users; Citizen, which only operates in New York City and San Francisco, receives its updates from a curated list of 911 calls.

This neverending notification stream is the main selling point of neighborhood watch apps, keeping their users on constant high alert, giving hourly reminders of how dangerous the world is: “suspicious” people ringing doorbells; three men wanted in connection with an assault five blocks away; a massive fire downtown (along with prompts for the user to go capture video); a shady man with a clipboard knocking on someone's door.

There's a difference between being informed and being threatened. Even if these apps were to make us safer, it's impossible to feel protected when these apps are always shouting about how much potential danger we're in. Spending so much time focused on that danger just leads to anger, depression, burnout. In our quest for safety, we've found ways to become more paranoid.

Ring and Nextdoor are most popular in white, upper-class neighborhoods, where the apps are awash with users labeling everyone they see a criminal. Door-to-door marketers and Latter-Day Saints missionaries used to be considered an annoyance, but now, they're potential burglars, casing homes to rob. In an article for The Week, Catherine Garcia notes that her local watch group has “no discussion, no consensus building, no coming together to find a solution” — just rage and unchecked privilege.

There's no proof that smart neighborhood watches reduce crime — the only one who claims to have stats proving they do is Ring, and they refused to supply the MIT Technology Review with any specific evidence. Some independent studies reported to the Tech Review actually showed that houses with Ring cameras are broken into more. But that hasn't stopped police departments across the country from giving Ring cameras out to citizens and monitoring the posts for potential crimes.

Much has already been written about the problems inherent in neighborhood watches: in short, that they convince paranoid white people to become “protectors of the neighborhood,” patrolling their neighborhood for “suspicious” people (re: people of color) to harass. But the convenience of the internet has given that prejudice new life. People of color already fear being profiled by law enforcement; now they have to worry about Ring cameras videotaping them and sending the footage straight to the cops. Police officials claim that they'll only look into videos that “meet their standards” for investigation, but when you consider how often police have harassed people of color simply for existing, it makes sense to take that claim with a grain of salt.

Ring has announced plans to integrate “suspicious activity detection and person recognition” into future software updates — in other words, software to automatically determine when a crime is being committed, and by who. But facial recognition programs have historically struggled at accurately identifying people of color, which begs the question of how we can trust Ring's cameras to treat them fairly. When asked by Motherboard whether posts on Ring are reviewed for racism, a spokesperson said: “The Neighbors app by Ring is meant to facilitate this collaboration within communities by allowing users to easily share and communicate with their neighbors and in some cases, local law enforcement, about crime and safety in real-time.”

Ring isn't the only app with a racism problem. On Citizen, crime alerts are followed up by accusations against every racial group under the sun. Nextdoor has had such issues with racial profiling that in 2016 it no longer allowed users to describe a suspicious person only by their race — at least two other descriptors have to be included. Many users don't feel that it's done enough to curb abuse on the platform,including the founders of Nextdoor themselves, who still see the potential for racial “friction” across the app.

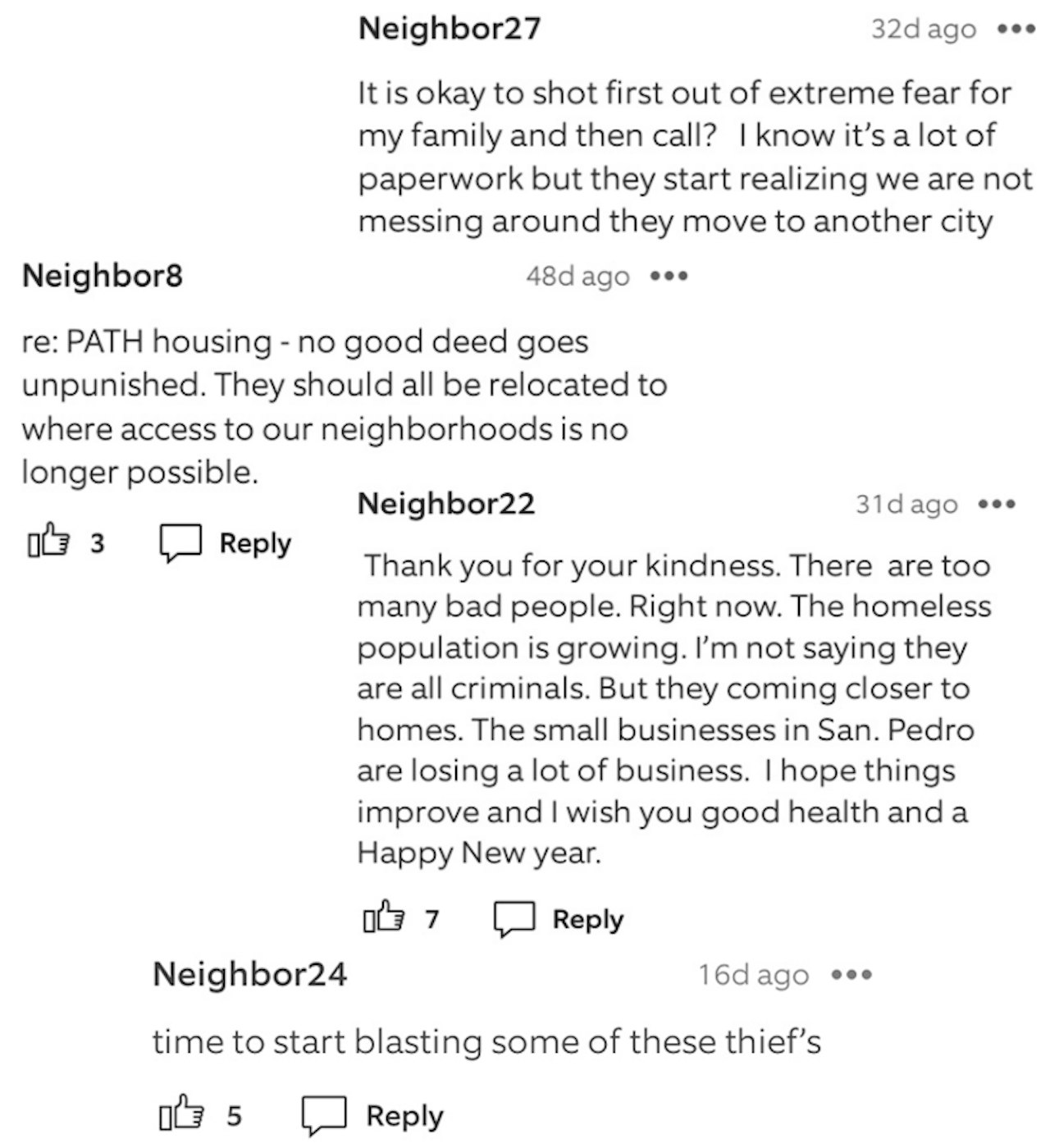

In Hermosa Beach, where the median income is over $120,000, classism has proved to be a problem as well. Last fall, a local homeless man was accused of masturbating inside a Starbucks, which led to a widespread effort across Ring and Facebook to track every homeless person in the community. One user called for all homeless people to be rounded up and shipped off to another town; another wondered aloud if shooting on sight would be okay — anonymous commenting systems letting a neighborhood's worst impulses run wild. Eventually, a police officer stepped in to explain the concept of due process.

Neighborhood watch apps guilt people into using the product, telling them that they're “helping to keep the neighborhood safe.” And tech companies are well-trained in the art of exploiting desperation to sell product. We want control over our lives, but really we're handing control over to devices, and that can have dire consequences for a community. This makes the real danger not the people in our neighborhood, but what's inside our homes. That's the end goal of the “smart household”: integrate tech into every part of the daily routine.