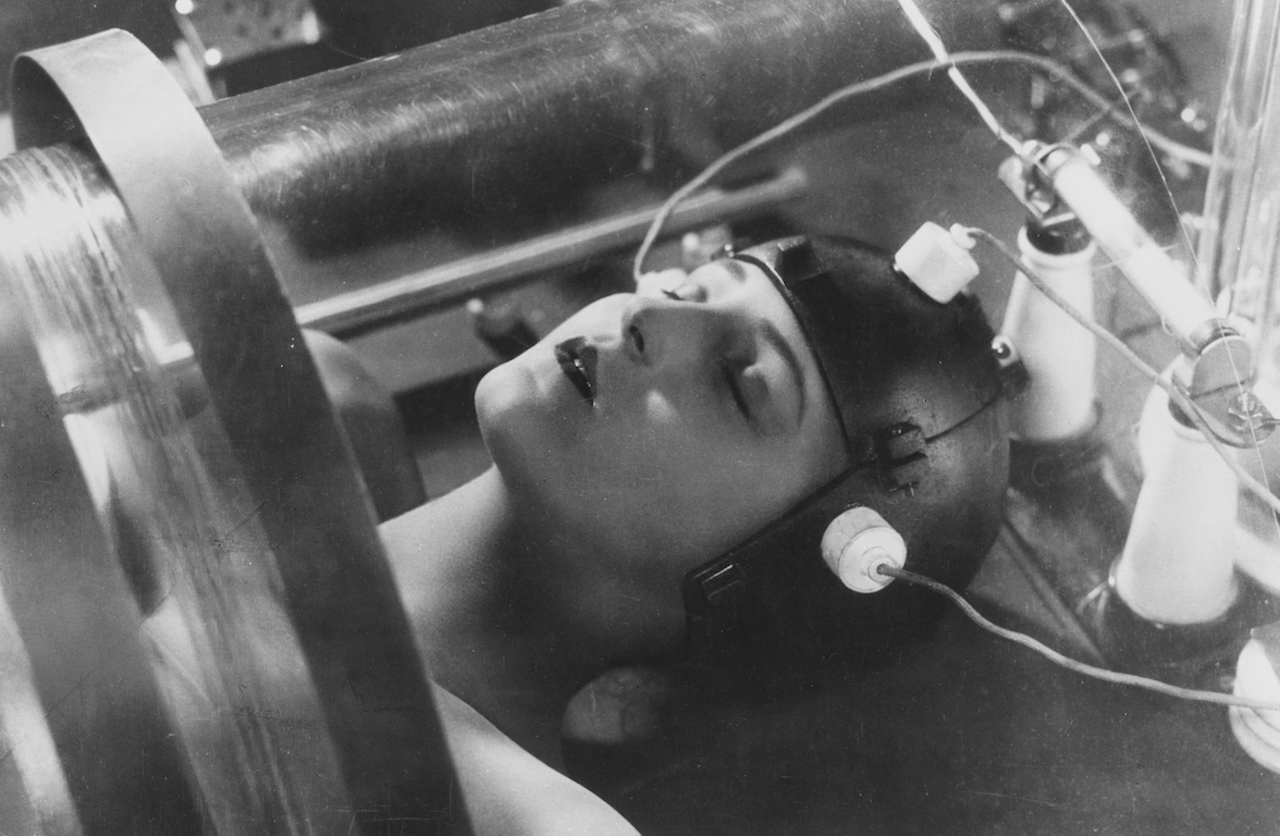

Stories of female androids are instructive fables that reveal how we respond culturally to women’s quests for autonomy. Sex, youth, and beauty are often the weapons at their disposal, and these characters have existed since cinema’s early years. Fritz Lang’s 1927 epic, Metropolis, provided the template that many science fiction films follow. In it, Brigitte Helm plays two characters: Maria, a human activist on the side of the working class, and the robot given her likeness. The machine that carries her looks is created to ruin Maria’s reputation. With her come-hither movements and electrifying presence, the machine is a hotbed of social disorder. She incites men toward murder and mayhem with ease.

Watch enough pop culture about female robots and a troubling pattern emerges. It isn’t a coincidence that chaos, death, and destruction soon follow as the machines fight their way toward freedom. These technological figures operate as metaphors for slavery, rape culture, and a discomfort with ambitious women who use their beauty as a weapon to carve their own path. The underlying themes have bubbled beneath the surface of science fiction for decades. A pivotal shift happened after the release of Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner, a 1982 film with a significant cult following (and a sequel starring Ryan Gosling in the works). The original movie marks one of the earliest cinematic examples of blending science fiction with noir. Blade Runner traffics in a simplistic rendition of noir’s gender politics in which women seeking power deserve fear and scorn. Since then, female robots have continued to inhabit the most pernicious ideas about femme fatales. They are lingering examples of the contradictory power that comes with fulfilling Western beauty ideals, what kind of women even have access to this sort of power, and male anxiety over female autonomy. Now, bots are back in the conversation, thanks to HBO.

In Episode 2 of Westworld, when William (Jimmi Simpson) makes his reluctant first trip to the theme park, the android host that greets him is quick to let him know “the only limit here is your imagination.” For most of the first season, these fantasies don’t extend far beyond the sort of ultraviolent ideas a teenage boy could cook up. It’s a series that wants us to ponder the exploitation it presents in the form of wild sex, gruesome violence, and implied rape. Ultimately, Westworld is a beautiful puzzle box with a hollow center, begging its audience to try to solve its riddles. The show’s greatest strength isn’t its capacity to spurn fervent theories, but the female androids at its center coming to terms with their growing consciousness and the narratives their creators have written for them — the innocent, farmhand/girl-next-door Dolores (Evan Rachel Wood) and the cunning brothel madam Maeve (Thandie Newton).

The female android holds a potent allure for filmmakers because of the heightened gender politics her story allows access to. Her figure is in music videos from artists like Bjork, Garbage, and Janelle Monae, whose work mines the archetype for its ability to discuss the cross sections of race, class, and gender (Monae's first EP is named after and takes cues from Metropolis). Her work interrogates something other filmmakers seem ignorant of: These fembots only have beauty in their arsenal when they embody the American ideal. For women of color, this sort of power remains out of reach. “The android is just another way of speaking about the new other, and I consider myself to be part of the other just by being a woman and being black,” Monae said in a 2013 Elle interview. “There's still certain stereotypes that I have to fight off, and there's still a certain struggle that we all individually have to go through.” Unlike the countless fembots that color the pop culture landscape, Monae’s makes us privy to the internal machinations of the characters rather than just making them reflections of their creator’s desires and anxieties. It's a stark contrast to a work like Spike Jonze’s Her, in which Joaquin Phoenix’s character falls for his very own disembodied A.I., voiced by Scarlett Johansson. Before she evolves, she’s the ideal for a grown man who prefers edgeless perfection and complete control over his romantic partner. When she does evolve, her essence is beyond comprehension.

Female androids tend to fall into a few limited categories: the cloying mother figures, muses, and rapacious sexbots who will use their eternal beauty and sex appeal to bring about a man’s downfall. If they gain consciousness, their stories seem to end just as they begin. They’re young and beautiful in a way that edges into uncanny valley territory, and typically white.

Ex Machina, Alex Garland’s lauded 2015 directorial debut, engaged heady conversations about identity and feminist lip service but still proved to have some of the most troubling ideas about which women have access to power. When programmer Caleb Smith (Domhnall Gleeson) wins a visit to the isolated home of techbro genius Nathan Bateman (Oscar Isaac), Caleb is told to judge whether the robot Ava (Alicia Vikander) truly has consciousness. Her flickering innards are on display, and Ava’s oddly smooth movements make her feel inhuman. While the androids of Westworld believe in their genders and identities even after coming into their own consciousness, Ex Machina poses the question of whether Ava’s perceived femininity is an essential aspect or a ploy.

Nathan has other creations, too. Kyoko, his silent Asian maid/sex toy is revealed to be an android later in the film, and her death is the key to Ava launching herself toward freedom. After Caleb breaks into Nathan’s study he comes across a series of recordings of Nathan interacting with previous humanoids. One of them, given the codename “Jasmine,” sits unmoving and completely naked. In the recording Nathan manipulates her lifeless limbs, drags her across the floor, and eventually leaves her discarded in a corner. She’s the clearest embodiment of the agency that Nathan’s creations lack. She’s also the only black woman we see and unlike the others doesn’t even have a face. From a certain angle Ex Machina can almost seem like a feminist fairytale — Pygmalion’s sculpture coming to life and deciding she doesn’t want to be his plaything — until the film reaffirms Nathan’s treatment of women of color when Ava picks parts off their powered-down bodies to make herself look more human before trotting off to a future in the real world.

Dolores, one of the central characters in Westworld, barely pushes the creative envelope that Ex Machina brought back into popular discourse. This isn’t to disparage Wood’s performance, which is perhaps the best of her career. But Dolores is calibrated to have just enough gumption not to come across as a lifeless, wan damsel – but not enough to seem like her own person. Over the course of this season, series creators Lisa Joy and Jonathan Nolan carefully teased out her backstory as the oldest host in Westworld. We’re also watching Dolores across multiple timelines from the early days of the park to present day. She seems trapped between what she was created to be (the innocent farm girl who sees goodness in the world) and something far murkier. Beyond figuring out the truth of her memories, who really is Dolores and what does she want?

“You said people come here to change the story of their lives. I imagined a story where I didn’t have to be the damsel,” Dolores says to William after killing off a group of former Confederate soldiers in Episode 5. When the camera pans up, revealing her steady hand holding a gun and her gaze focused, it’s meant to be a triumphant shot. The swelling score highlights the purpose of the moment as a feminist rallying cry. Dolores, the picture-perfect American girl, has decided to finally write her own narrative. But just when we think the series has dismantled her dream girl image we pivot back to seeing Dolores brutalized by William’s friend Logan (Ben Barna), revealing the interlocking machinery underneath her human visage. She starts to seem as confused about her identity as we are. As Emily Nussbaum wrote in the New Yorker, Westworld feels like what happens to an HBO drama when it becomes self-aware about its own tropes and limitations but still doesn’t know how to move beyond them. Westworld has a remarkable opportunity to advance the scripts for female A.I., but — at least during its first season — it didn’t do this through Dolores.

“I understand now. This world doesn’t belong to them. It belongs to us,” she says to Teddy before she slinks behind Ford (Anthony Hopkins) on stage and blows his brains out in the finale. Ford has of course engineered this robot uprising as his final stroke of genius as he lets go of the reins of the world he created. But what makes this more than just a visually rich, savage affair is that Dolores came into her own moments before.

After facing her role in the death of Arnold (Jeffrey Wright), Westworld’s other chief architect in its early days, Dolores sits down across from him (or at least imagines as much). “Do you know who you've been talking to? Whose voice you’ve been hearing?” Arnold asks her. Dolores closes her eyes, and when she opens them she doesn’t see Arnold sitting across from her but herself. It’s a trippy, thrilling image seeing these two versions of Dolores sitting across from each other. This story about a woman coming into her identity lends pathos to the violence Dolores commits later. All of this isn’t enough to distract from the ways her story didn’t live up to its potential thanks to the needlessly overcomplicated timelines that masked a simple narrative. But seeing Dolores come into her own and lay waste to the people who have controlled her life promises a far more interesting arc for Season 2.

The female android holds a potent allure for filmmakers because of the heightened gender politics her story allows access to.

On the other hand, watching Maeve discover her own identity in Westworld is like catching a glimpse of a more expansive future for female android characters, specifically for women of color who line the margins of these stories. In the premiere, a lab technician makes a joke about another prostitute host: “A hooker with hidden depths? Every man’s dream.” But Maeve doesn’t hide a heart of gold. She has a steely will and a venomous sense of humor. Part of the character’s success can be attributed to the backstory of The Man in Black killing her daughter. The memories of this former life often float to the surface at inopportune moments. While none of this may be “real,” the emotions she demonstrates are. Thandie Newton also brings something the show desperately needs elsewhere: fun. After roping two reluctant, annoying techs into altering her programming, Maeve gains the ability to control other hosts, letting her write the narrative as she chooses. Her eyebrow is cocked, and her walk is full of swagger. Newton gives the character a been-there-done-that sort of insolence. More importantly, Maeve has a stronger morality and sense of dignity than her flesh-and-blood creators.

“At first I thought you and the others were gods. Then I realized you’re just men,” Maeve says in Episode 7. She relishes each syllable. She doesn’t fall into becoming a flat symbol for “empowerment” or other traps that beset women of color. The finale reveals that all of Maeve’s revolutionary aims are just a new narrative written for her. She refuses to believe that she isn’t in control of her own destiny. But Maeve has never been that easy to define. The last thing we see of her in the finale is her deciding to get off the train that would have taken her out of the theme park, presumably to go back and find the daughter she had in a previous narrative. This seems to fly against her new programming, which has been all about escaping Westworld. In fact, creator Jonathan Nolan said to Vulture that this moment marks “the first real decision she's made all season. Which is, she's not going to fulfill the script she's been given, which is to take this train wherever it's going and do whatever else she's programmed to do. We're no longer in programmatic or prescribed behaviors. She's improvising, and we're right there with her.” Maeve is rare and important — a black woman as the hero of her own science fiction epic and a shot of pure fun into a genre that sometimes feels woefully morose.

Maeve is Westworld's offering that seems most rooted in the future. She isn’t just seeking her own freedom — she wants a revolution. She displays kindness in unlikely moments and bypasses the tired damsel-into-femme-fatale narrative to become something far more entertaining. She’s not a symbol. She embodies the thrill that comes when dream girls don’t become nightmares but something far more subversive: their own people.