In 1902, the German-Japanese poet and art critic Sadakichi Hartmann announced to the public that he would be staging “A Trip To Japan in Sixteen Minutes,” the world’s first ever scent-performance, in New York. His idea was to create a work of art that appealed to his audience’s sense of smell in order to evoke a journey, like music or the newly burgeoning art of cinema might for one’s hearing or vision. Until this point, he claimed, there had been no apparatus that could provide an audience with what he called “a melody in odors.” This magical apparatus? The electric fan.

The idea was seductive. According to many scientific studies, smells have a greater power to evoke memory than our other senses, and inspire more forceful, visceral reactions. (Think of the way you recoil whenever stepping onto a train that smells like piss.) In Hartmann’s case, however, the performance was a disaster. The influx of heavy, floral perfumes was intended to evoke different countries on a journey by sea to the East, but the crowd, with only the visuals of Hartmann and two powdered women in kimonos sliding smell-soaked fabrics in front of a fan, was not impressed. Instead of the planned 16 minutes, Hartmann was heckled off stage after just four. In a 1913 essay about the performance, he wrote: “The disconnectedness of the various waves of pleasurable feeling make it impossible to carry out this act to the same pitch of perfection as music and painting.”

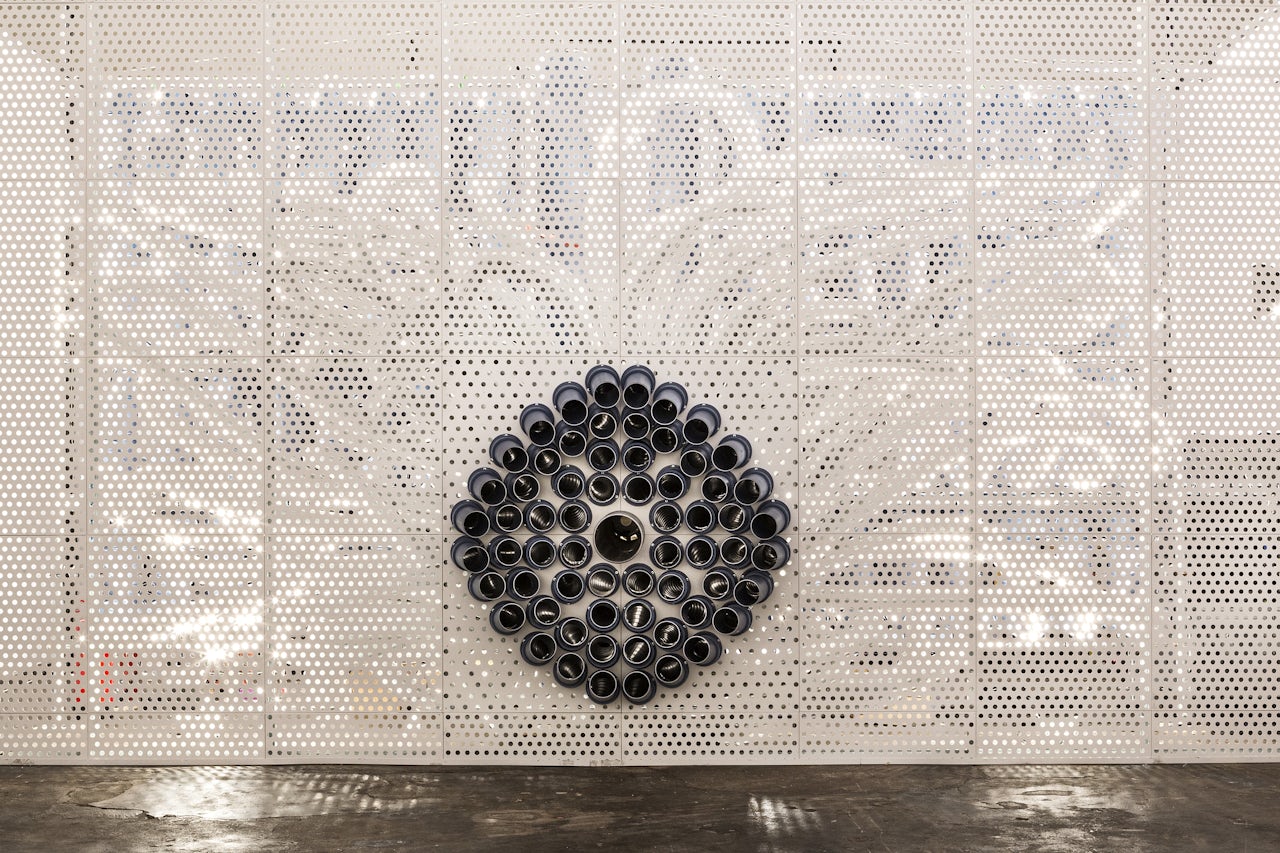

More than 100 years later, Hartmann would have been astonished to witness the Smeller 2.0 at Berlin’s Martin-Gropius Bau museum, a temporary installation of a machine made by the artist Wolfgang Georgsdorf, that pumps smells one after another into a room. Though it first debuted in 2012, the presentation I attended took place in 2018. It started out unassumingly. I walked into a small white room with a perforated metal screen at one end and a rosette of pipes in its center, and waited.

According to other artists in the smell art community, the Smeller does what no one else in the intervening time period has ever managed to do: it pumps a series of defined, distinct smells into the room, one after the next. The scents dissipate just as the next one arrives: horse, then cinnamon, and then something that reminded me of an underground car park. Different types of berry, in vibrato, one after the other. No sound, no visuals, just a scent, and then another, every inhalation a new surprise. At one point the woman next to me cried out and held her nose in disgust as the deep, rich scent of gorgonzola filled the room.

The Smeller is the brainchild of Georgsdorf, who, like Hartmann, has many talents — besides being an artist, musician, and a composer of smells, he also wrote a dictionary of Austrian sign language. The Smeller 2.0, which most closely resembles a pipe organ with its tangle of pipes and vents, is the size of a small coffee shop, and uses the museum’s 19th-century windows to ensure perfect airflow, like a humongous air conditioning unit. It found a home at the Martin-Gropius Bau for several months in the summer of 2018, but has been installed at several other locations in the past. Its 64 chambers can each be loaded with a different scent, which can then be “played” like a musical note by the artist or his assistant backstage, using a midi keyboard and digital-to-analog converters to turn electrical impulses into physical movements in the instrument.

“I'm abusing a sound system," Georgsdorf joked as we snuck into the technical room that sits behind the performance theater itself. The 60 year-old Austrian visual artist is short and bald, and wears thick round black spectacles and suspenders. He was chatty, sincere, and personable, keeping an entirely straight face when explaining why compounds from fecal matter are important ingredients in perfumery, for example. He has spent more than 20 years getting his Smeller in front of an “odience,” which is what he calls those who experience it. He made the first prototype in 1996, but the idea has been in his head for almost his entire life. “When I was four or five, I had my first olfactory ‘panflute,’ you could say, with many different flasks next to each other,” he said, miming moving his head left to right along a line of bottled scents.

When we met, Georgsdorf had just finished his patent application for the Smeller, which involved deep research into the previous attempts at creating a kinetic smell instrument. “What I saw was a series of very entertaining, triumphant failures,” he said. Sadakichi Hartmann’s electric fan was only the beginning of the 20th century’s experiments in olfactory performance, which tended to use cinema to provide context. In 1906, before movie theaters even began to use sound, a newsreel of the annual Rose Parade in Pasadena, CA was shown in a theater in Pennsylvania, with electric fans blowing the scent of the flower through huge cotton pads into the audience.

From then on, there were several efforts to to pump into theaters not just one, but many different scents to correspond with a movie’s plot points. The most famous example of this cinema-olfaction hybrid was Hans Laube’s Smell-O-Vision, which debuted with the 1960 film The Scent of Mystery: In specially-equipped theaters, 30 different odors were dispersed from audience members’ seats when triggered by thereel. Shortly before Smell-O-Vision’s premiere, a similar technology, Aromarama, which used a cinema’s air conditioning system to diffuse odors into a theater, was introduced. Despite something of a technology race between the two films, neither one was successful. The New York Times called Aromarama a “stunt,” and its odor sequences “elusive, oppressive or perfunctory and banal.” In the end, the films’ impact lingered no longer than the smells they disseminated into movie theaters.

More pungent neologisms followed: John Waters’ 1981 film Polyester came with a scratch and sniff card entitled “Odorama,” containing scents like air freshener, skunk, and pizza, that corresponded to numbers flashed on screen; this model was later copied by Nickelodeon under the moniker “Aromascope.” In 1999, the iSmell, a kind of shark-fin shaped USB drive with an air freshener attached, tried to offer consumers scents triggered by their internet browsers. It raised $20 million in funding before swiftly imploding due to a lack of market interest, and filing for bankruptcy, landing itself on plenty of “worst startup ever” list.

“People have misunderstood on a physical level, a chemical level, on a perceptive level, on a psychological level,” Georgsdorf told me of these other projects. In particular, the comparison with visual and audio performance has caused confusion. “We are talking here about a new form of art that does not deal with waves such as light and sound, but with particles,” he said. And particles, unlike waves, don't just cease to exist when a stimulus stops producing them. They linger. Hence Georgsdorf’s careful control of air through the Smeller — his 523 cubic yard performance room turned almost as much air per hour as the air conditioning in the rest of the building — all 130,800 cubic yards of it.

“The vision is a new form of art that had never existed because simply the technology was not there. How can I make piano music without a piano?“

The question remains, however, of how to interpret Georgsdorf’s work as art, beyond recognizing what his instrument can do. The issue here is mostly cultural. There is a widespread paucity of knowledge in our comprehension of the olfactory, while other animals are “reading newspapers with their noses,” as Georgsdorf put it. Scientists are still figuring out the intricacies of how our brains decipher scents, although there is evidence that olfactory data is more deeply connected with memories and less connected to language, and therefore more emotional.

This makes scents difficult to talk about. Think of how few adjectives English speakers have for smells, in comparison to sound, or sight. We most often resort to talking about the source of the smell, rather than the smell itself: something might smell like “the pages of a new book,” or “an old school,” or “a wet dog.” (There are a few exceptions to this rule across all human languages: Speakers of the Asian language Maniq, for example, have an abstract smell adjective associated with the hog badger in the dry season, among their other, highly specialized odor vocabulary.) The sequence of smells that I experienced in the Martin-Gropius Bau took my nose to the forest, a church, and the kitchen cupboard, but it was hard for me to understand what it all meant. Georgsdorf was unperturbed by this. “It depends what you mean by ‘understand,’” he said. “It's easy to understand the music of Justin Bieber but it's not so easy to understand the music of John Cage.”

He acknowledged that at least some of this difficulty lies in the artform itself. “We have 4,000 years of music history and we have zero thousand years of Osmodrama history!” he said. “The vision is a new form of art that had never existed because simply the technology was not there. How can I make piano music without a piano?”

Occasionally, Georgsdorf seemed frustrated when discussing the slowness of institutions to understand the potential of his machine, which he saw as far from the final iteration of its potential. In its current form, the Smeller is difficult, and therefore expensive, to perform with, requiring one-off installation to fit the space. But, if the Smeller 2.0 corresponds to the Lumiere brothers’ rattling black and white projector of the 1890s, Georgsdorf has his eye (and nose) on the equivalent of retina display: Smeller 5.0, or even 10.0, “which would be an olfactory synthesizer. Anyone can play it, and anywhere.” As always, the possibility of something like this comes down to financial investment: “I know how to get there, if I had the money,” Georgsdorf said. “In a few years you would have a completely different hardware. I'm working already on apps so that we can all compose [smells] together.” Every city could have a communal Smeller, he suggested, a location-fixed apparatus like a cinema or a church organ.

For now, Georgsdorf has resisted mass-market ambitions. He seemed particularly irritated by the “wishful thinking” of the failed iSmell and their wasted $20 million investment. “Can you imagine what I could do with that money?” he asked. But Georgsdorf’s work isn’t only about making smells into art. He is currently working on research with the University of Dresden and University Hospital Berlin to test whether subjects with depression see an improvement in their symptoms after experiencing the distinct series of scents from the Smeller. Preliminary results suggest they do, but regardless of what early findings might show, Georgsdorf’s machine is the only apparatus in the world that even allows such a thing to be tested.

“We're standing in front of a new phenomenon and it's not a gimmick, it works,” Georgsdorf said. He’s right; it does. He has fulfilled the early promise of Hartmann’s wacky experiment. When I stepped outside the museum, I wondered: What other smell experiences have I been missing out on?

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly claimed the Smeller debuted in 2011, not 2012.