Ted Bundy, unfortunately, is back. A new movie, Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil, and Vile premiered at Sundance on January 26; around the same time, Netflix launched its new Bundy documentary series, Conversations with a Killer. The streaming platform yesterday announced that they’d bought the rights to the movie as well, thus compounding their status as the Bundy Channel. Three decades after his execution Bundy, who killed at least 30 women and girls, often raping them and having sex with their dead bodies, has returned to haunt our imaginations.

Even more than usual for a serial killer, there are fears that when one discusses or otherwise represents Bundy one will end up “romanticizing” him. The movie, in particular, has led to those fears being raised afresh — fears the plausibility of which might best be observed by the various shades of “er, actually, your fav Bundy was pretty problematic” takes seen cropping up online.

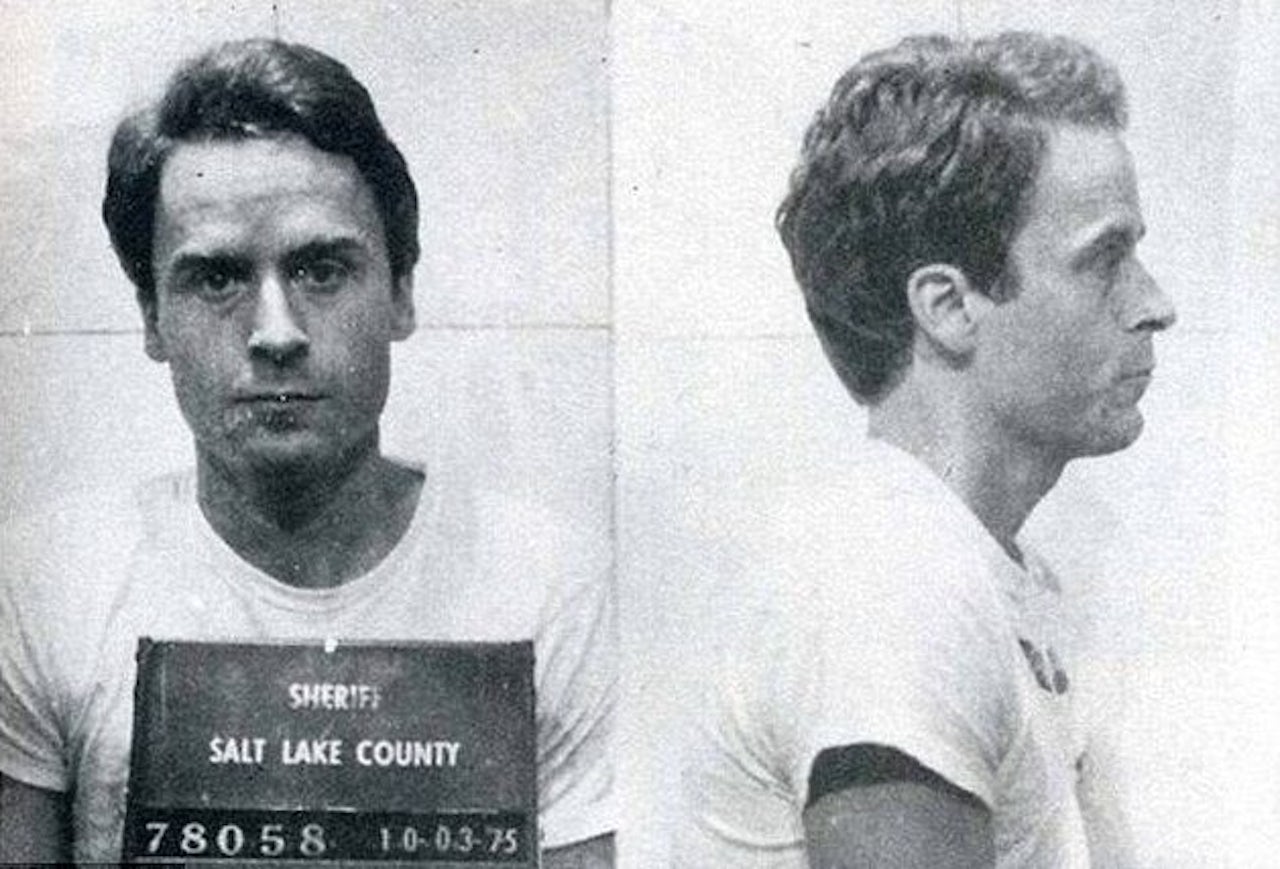

These fears are linked to the myth of Bundy’s “handsomeness” — a myth compounded by the fact that Zac Efron is playing him in the forthcoming movie (former teen heartthrobs playing killers aside, how on earth Glenn Howerton — a man who has effectively been playing Bundy on It's Always Sunny In Philadelphia for the best part of 15 years — was passed over for the role is beyond me. Perhaps he was afraid of being typecast). But when one looks at pictures of Bundy, “handsome” never seems quite right. He was not a man whose appearance would, under normal circumstances, have drawn much comment at all (one reason police have claimed he was hard to catch was due to his peculiarly “chameleon-like” appearance: he looked different to different people, in different situations, at different times). Rather, this myth of Bundy's “handsomeness,” this idea that he was in some way a compelling or attractive person, has in my view emerged for a quite different reason.

“He was a very nice person,” Bundy's friend Marlin Lee Vortman, whom he met through his work as a Republican activist, says in the documentary. “He was the kind of guy,” he said of the serial murderer of other people's sisters, “you'd want your sister to marry.”

To these successful, professional men Bundy didn't seem like a killer — because he seemed somehow like them.

“Take care of yourself, young man,” says the judge at Bundy's 1979 murder trial, just after sentencing him to death for the killing of Lisa Levy and Margaret Bowman. “It’s a tragedy for this court to see such a total waste of humanity,” he adds — referring not to the two women, but to Bundy. “You’re a bright young man. You’d have made a good lawyer. I would've loved to have you practice in front of me. But you went another way, partner.”

“He seemed like ���one of us,’ if you will,” says the lawyer Bundy hired in Utah for his 1976 trial, at which he stood accused of the kidnapping and assault of Carol DeRonch. “He was very nice, his clothes were pressed,” notes the psychiatrist who assessed him before it.

This is the real fascination of Bundy: what lurks behind his mysterious “handsomeness.” To these successful, professional men he didn’t seem like a killer, because he seemed somehow like them. Despite the fact these people now know — and in some cases always knew, the whole time they knew him — what Bundy did, there seemed like there was something about him, his affect, his way of carrying himself, that they recognized as kindred.

Bundy was active before neoliberalism achieved its present hegemony, but in many ways his subjectivity was aligned with the outlook it would foster: he shared the tendency — common among bankers or ventures capitalists — to see things only in reductive, brutely functional, or quantitative terms. In the Netflix series, when trying to describe his first girlfriend, the woman who he claims “inspired me to look at myself and become something more,” Bundy can’t stop using the word “car.” “She's a beautiful dresser, beautiful girl. Very personable. Nice car, great parents. We spent a lot of time driving around in her car. You know, making out in the car... told each other how much we loved each other.” In Bundy’s eyes, the woman is barely separable from the vehicle she drove. “When I met Marlin (Lee Vortman), he says a bit later, “I was attracted to him because his wife could cook good sushi.” He also admired Marlin's Volkswagen, and later purchased a similar one of his own: both the wife and the car were viewed as products his friend owned.

“Women are possessions,” Bundy said in describing the psychological profile of the “type of person” who would have committed his crimes (at this point he is speaking in the third person, a ruse designed by his interviewer to avoid him having to admit his guilt). “Beings which are subservient, more often than not, to males. Women are merchandise.” Bundy objectified women in the most extreme way.

But we are still rehearsing this received idea of Bundy’s lost potential — the potential to be the sort of man we would trust to represent us in court or in office, to greet us warmly when he comes over with our sister and her kids for a family dinner. A notable number of people looked at Bundy and thought, you know what: short the 30-odd dead women and girls, this could be the sort of man we’d want in charge. And what, we have to ask ourselves, does that tell us about the people who actually end up getting put in charge?

When Bundy was growing up, according to a classmate interviewed for the documentary, there seemed to be something almost indefinably “off” about him, which made it impossible for him to fit in. “He just didn't seem to be all there, all present in some way. There was just a gap in him,” the classmate says. But when he started to participate in Republican party politics, Bundy found “his people.” He got invited to dinners, drinks. He claims he got laid for the first time while on the campaign trial. “There was a life there,” he says in the documentary, “a life that had been missing for me.” He continues: “I’ve always been anti-union, anti-boycott. I just wasn't too fond of criminal conduct, and using anti-war movements as a haven for delinquents who liked to feel that they were immune from the law.”

This all seems a bit ironic, considering what Bundy did. But on another level, it is apparent what he means — he is referring to the law not as a system of justice, but a violent force that keeps people in their place, keeps marginalized people down. In this sense, Bundy was a perfectly law-abiding citizen: the serial murderer of women as an agent of the patriarchy, directly asserting the violence which any conservative would have felt was being opened up by the newly permissive post-sexual revolution society.

For all the platitudinous talk of evil they tend to generate, serial killers are social phenomena; Bundy was part of an identifiable 1970s and ‘80s “serial killer boom.” The causes of that boom are disputed, but the point is clear: killers are not only produced but also enabled by the society in which they exist. With Bundy in particular, that latter point is starkly true. And this is the secret behind his tendency to get “romanticized” — his hidden complicity with the forces of power. There’s a dark joke to be made here about the horrors Bundy could have been responsible for if only he’d chosen a different path.