When the year comes to an end, music publications reflect on industry trends and rank the top 50 to 200 albums of the year. It’s a great way for readers to stumble on releases they might have missed or otherwise not have listened to, especially for Rob Mitchum, a Chicago-based music and science writer, who has been aggregating these lists to produce gigantic, multi-genre meta-lists since 2013.

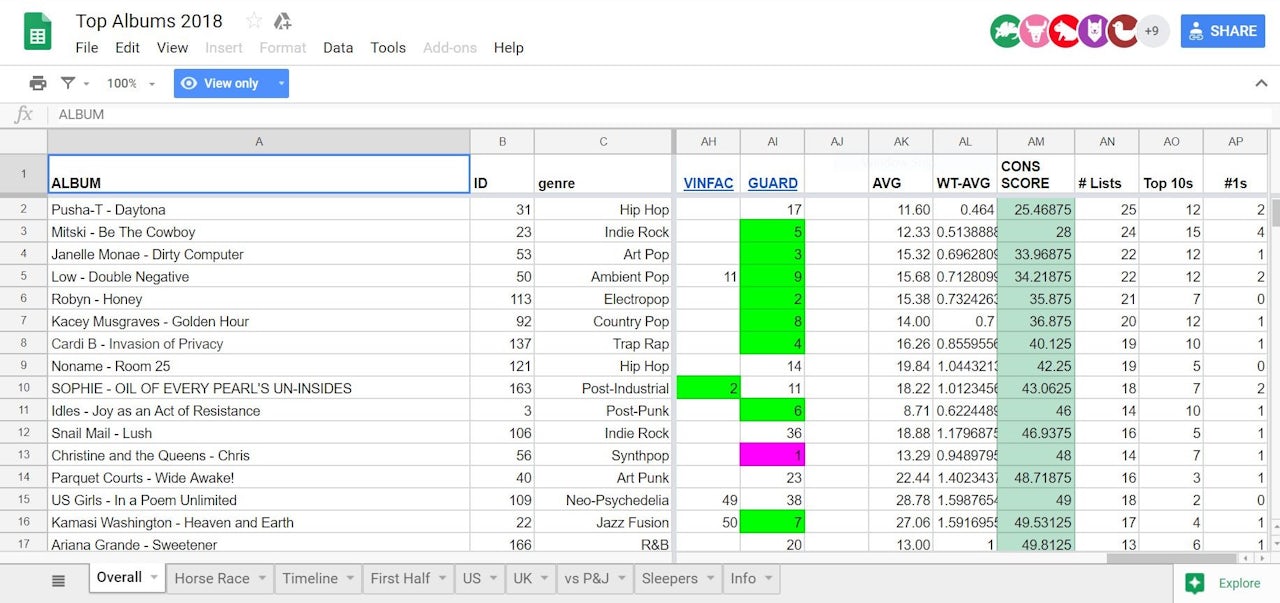

“Part year-end cheat sheet, part a primitive attempt at music sabermetrics, part a commentary on modern criticism, and part (the biggest part) a music-geek cry for help”, or so Mitchum called them in a previous piece, his spreadsheets started as an exercise in data science while he was working at the University of Chicago’s Data Science for Social Good program. “I have kids, so it’s harder to keep up with music releases during the year,” he told The Outline over the phone. “The program covered a lot of computer science and data science, I was learning to program, and I was looking for my own dataset to play around with.” He made a Google spreadsheet, listing all of the albums featured on lists from SPIN, Pitchfork, and 22 other publications; he also calculated each album’s average ranking on the lists it was featured, as well as a “consensus score” that penalizes albums for not appearing on any given list.

“I didn’t expect people to care,” Mitchum said. “I posted the list on Twitter, expecting maybe two or three people to find it interesting.” But the spreadsheet received a lot of attention, and it soon became a tradition on music wonk Twitter, with people tweeting at him near the year’s end to get his spreadsheet up. Upwards of twenty people anonymously lurk on the 2018 spreadsheet at any given time, and he’s seen over a hundred users at once. “People are generally really appreciative [of the project], and say that it’s helped them sport trends and find new music to listen to,” he said.

Now that the Album of the Year List Project has been six years in the running, interested folks can compare chart sleepers and breakout albums from different years. Mitchum called 2018 “the most wide-open year yet” in terms of a consensus pick for the top album, which Pusha-T’s Daytona narrowly won over Mitski’s Be The Cowboy. “It’s hard to say what the consensus [score] actually means, but it usually shows what album is well-presented on best-of-year-lists across the board,” Mitchum said. “2018’s numbers looks closest to those in 2014, when FKA Twigs’s LP1 also became the consensus pick despite only topping two lists, like Pusha’s Daytona.”

Top Albums of 2018, aggregated

- Pusha-T - Daytona

- Mitski - Be The Cowboy

- Janelle Monae - Dirty Computer

- Low - Double Negative

- Robyn - Honey

- Kacey Musgraves - Golden Hour

- Cardi B - Invasion of Privacy

- Noname - Room 25

- SOPHIE - OIL OF EVERY PEARL'S UN-INSIDES

- Idles - Joy as an Act of Resistance

“I thought Kanye would hold [Pusha-T’s rankings] back, but [the album] survived Kanye dragging him down,” he added. “It’s very impressive.”

When asked about why there isn’t a breakout pick for best album of 2018, Mitchum pointed to a paradigmatic shift in music writing that’s led to better representation and coverage of music genres across the board, with more albums thus vying for preferential treatment. “Music writing has become a lot less indie rock-focused, and there’s a better diversity of music opinion, which levels the playing field a lot for albums. Ten years ago, in Pitchfork’s heyday, Low’s Double Negative would have won out as an experimental rock album,” he said. “You can see in 2013 already how critics have been broadening out to other genres. If I had started the project fifteen years ago, it’d be more apparent how music writing has changed.” Heavy-hitter favorites like Beyoncé and Drake also released projects to no extraordinary critical acclaim this year, allowing for newer and lesser known artists to dominate the charts.

And it seems that critics favor shorter projects despite album trends: Looking at the numbers, none of the top 10 albums on Mitchum’s spreadsheet run for more than 50 minutes. The longest project is Low’s Double Negative at a concise 48:49 minutes. (The indie rock band’s 1994 debut, I Could Live In Hope, ran for almost an hour (57:05.) Daytona could even be considered an EP, given its 21:08 runtime. Mitchum compared Daytona to Kamasi Washington’s Heaven and Earth, which came in at a respectable 16th on his spreadsheet, and runs for a whopping 3 hours. “You could easily listen to Pusha’s record ten times in the time it takes to listen to Washington’s once! It really helps to spend lots and lots of time with a record; the more you listen to it, the more likely you’re able to find interesting things to like about it.”

Mitchum stressed that it’s good for music when critics move towards a wider variety of genres, and more consideration of the popular and the mainstream. “There’s a lot of alarmist writing on algorithms and streaming, but data-driven music discovery can be good… and I guess that [my] project is another way of saying that,” he said. He also noted that he’d like to build his own basic music recommender application one day, and understand “what’s under the hood of a simple music recommendation algorithm that quantifies seemingly unquantifiable things like ambiance and noise level.”

In the meantime, Mitchum continues to trawl for new music within the top 50-100 range on lists across publications, especially for albums that place relatively high on the lists they’re on, or strong records from undercovered genres like metal. In his view, the most interesting best-of-year lists are the ones that contribute a lot of records that might not place elsewhere, if at all, such as Bandcamp’s (he didn’t include Bandcamp in his spreadsheet, as the organization only lists records that are on sale on the site). “It comes down to taste,” he told me, noting how he “gets” fewer and fewer records with each passing year. His favorite list to put in the spreadsheet usually comes from British site The Quietus, which features “more avant-garde, ambient stuff” and is generally more to his taste.

“The best lists are those that don’t take it too seriously,” he concluded. “It’s an end-of-year list, you don’t need to get too uptight about it.”

You can find all past spreadsheets on Mitchum’s website.